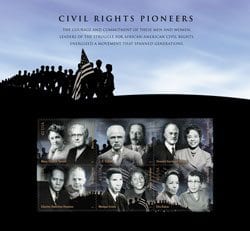

Author: AP /Earl Gibson IIIIn this photo released in New York on Saturday, Feb. 21, 2009, by the U.S. Postal Service, a stamp collection bearing photos of 12 civil rights leaders is shown. On the top row are (from left): Mary Church Terrell; Mary White Ovington; J.R. Clifford; Joel Elias Spingarn; Oswald Garrison Villard and Daisy Gatson Bates. On the bottom row are (from left): Charles Hamilton Houston; Walter White; Medgar Evers; Fannie Lou Hamer; Ella Baker and Ruby Hurley.

Author: Lolita Parker Jr.In this photo released in New York on Saturday, Feb. 21, 2009, by the U.S. Postal Service, a stamp collection bearing photos of 12 civil rights leaders is shown. On the top row are (from left): Mary Church Terrell; Mary White Ovington; J.R. Clifford; Joel Elias Spingarn; Oswald Garrison Villard and Daisy Gatson Bates. On the bottom row are (from left): Charles Hamilton Houston; Walter White; Medgar Evers; Fannie Lou Hamer; Ella Baker and Ruby Hurley.

2009: A year of pride, celebration, reflection

The year 2009 has already proven to be one of the most remarkable in our nation’s history. As I reflect on this country’s steady, if erratic, march toward justice and equality, I am struck by the number and variety of important anniversaries and events taking place this year.

When I look at each not as an isolated occasion, but as a piece of a broader tapestry, I see both cause for celebration about some unmistakable breakthroughs and a need for continued vigilance and action, especially on the part of our youth. I see a path forward, but it remains filled with potholes and potential detours. We must be realistic and idealistic at once, as we consider how to build upon all of the efforts that brought us to this historic moment.

Of course, the inauguration of Barack Obama on Jan. 20 as our nation’s 44th — and first African American — president overshadows almost every other landmark event this year. Not only was this achievement one that appeared to be unfathomable as recently as a year ago, it also represented a moment for celebration across the globe. In less than two months in office, President Obama has already pledged to close the prison filled with alleged terrorists in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and to bring our troops home from Iraq. He has also engineered a $787 billion stimulus package intended to aid our neediest communities, including Roxbury, Dorchester and Mattapan in Massachusetts, over the next 18 months.

But in order to more fully understand how Obama’s election became possible, we need to look at a series of other anniversaries and occasions that have taken place this year. They provide critical pieces of the puzzle, even though they are not nearly as well-known to the public.

On Feb. 12, 2009, this year, we celebrated the 200th anniversary of the birth of Abraham Lincoln, our 16th president, who both challenged the evils of slavery and led a deeply divided nation during one of our most wretched and bloody wars. On the same day, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) celebrated its 100th birthday. This is no coincidence.

One of the NAACP’s founders, Ms. Mary Ovington, thought it would be fitting to start a civil rights organization on the 100th anniversary of President Lincoln’s birth. And so, on the same day — 100 years apart — we celebrated the births of the man who helped bring about the end of slavery, and of an organization that continues to fight for full equality for African Americans living in the United States.

This year has also brought occasions for serious reflection. Our nation’s greatest leader, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., would have celebrated his 80th birthday on Jan. 15. Dr. King has now been dead longer than he lived, a fact I find startling and sobering. Yet his legacy remains as strong as ever. We celebrate his birthday as a national holiday every year. This recognition allows us to take some time to appreciate his magnificent and courageous accomplishments each time we are reminded of the progress in achieving racial equality that occurred both during and beyond his lifetime.

The year 2009 has also ushered in two other very important events. On Feb. 21, Ella Baker, Daisy Gatson Bates, J.R. Clifford, Medgar Evers, Fannie Lou Hamer, Charles Hamilton Houston, Ruby Hurley, Mary White Ovington, Joel Elias Spingarn, Mary Church Terrell, Oswald Garrison Villard and Walter White had commemorative U.S. postage stamps issued in their honor.

This recognition offers us an opportunity to appreciate the women and men, black and white, who contributed to some of the most important civil rights victories in the history of our country. One among them holds a very special place in my heart.

Charles Hamilton Houston was a 1922 graduate of Harvard Law School and a civil rights legend. He led the movement to end Jim Crow laws throughout this country, and is known as the architect for the legal strategy that was argued before the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education.

This recognition of Houston is more than just richly deserved and long overdue. It also reminds us of the importance of the past as we look toward the future. It is ironic that Charles Hamilton Houston was born in 1895, the same year W.E.B. Du Bois became the first African American in the history of this country to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard University.

At the same time as we contemplate the value of our history, we recall that though Carter G. Woodson, born in 1875, did not finish high school until he was 20 years old, he still went on to not only receive a variety of degrees, but to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1912.

This award to Woodson is important because it shows that we should never give up on anyone as he or she strives to succeed and achieve in a competitive environment. Carter G. Woodson also gave us what was then known as Negro History Week, which has since become an important month of celebration, Black History Month.

The timing of these celebrations coincides with another historic event. Nationally noted journalist and commentator Tavis Smiley has been hosting events called the “State of the Black Union” since 1999. The 10th anniversary of this annual forum was held on Feb. 28, 2009.

At the celebration, Smiley announced that he had co-written and would soon release a new book with Harvard Law School graduate Stephanie Robinson, entitled “Accountable: Making America as Good as Its Promise.”

The book is designed to follow up on Smiley’s very successful previous books, “The Covenant” and “The Covenant in Action,” both of which lay out the challenges faced by the black community in the 21st century.

“Accountable” is not only timely, but also allows us to listen to important and honest stories about both the successes experienced by the black community and some of its most noted failures. It will review data about the challenges we face in closing the racial achievement gap, providing universal health care, reforming our criminal justice system, creating jobs — including green jobs — and ensuring that our communities benefit from the election of an African American president.

I had the pleasure and privilege of serving as one of the panelists during the 10th anniversary of the “State of the Black Union” conference. The participants reflected upon the wide range of our political, public interest and community organizing, and laid out a blueprint to pursue some of the important issues that face not only African Americans, but all Americans. The participants included, among others, the Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr., the Rev. Al Sharpton, U.S. Rep. Maxine Waters, D-Calif., Republican National Committee Chairman Michael Steele, green jobs advocate Van Jones, Michael Eric Dyson, Cornel West and economist Dr. Julianne Malveaux.

I can’t help but note the symmetry in what may at first seem like disconnected events and anniversaries. The 100th anniversary of the NAACP, the birthday of Abraham Lincoln, the stamp recognition of 12 civil rights leaders, the inauguration of Barack Obama as president and the publication of the book “Accountable,” when viewed together, convey a single message: Although much progress has been achieved, much work still needs to be done to improve the quality of life and the prospects for equality for everyone living in the United States.

At the most basic level, the comments of Charles Hamilton Houston, made nearly a century ago, stand as a challenge to us today. He told his students at Howard University, including eventual civil rights legends Thurgood Marshall and Oliver Hill, that “a lawyer is either a social engineer or a parasite.” This statement reminds each of us of our responsibility to make our communities stronger and more just. Houston fought valiantly to end racial segregation in every facet of American life with a determination that probably cost him his life.

He died on April 22, 1950, at the age of 54, years before the Brown v. Board of Education decision was issued on May 17, 1954. Yet Houston left his fingerprints all over the decision that was ultimately rendered by the Supreme Court abolishing “separate but equal” schools, just as he influenced almost every Howard law student who went on to fight so many of the important civil rights legal battles of the next few decades. In so doing, he showed the nation that Howard University and other historically black colleges and universities could produce talented and determined professionals who would change America in ways that seemed unimaginable and unforeseeable at the time.

When we examine the history of our legal system over the past few decades, it is impossible to over-emphasize the profound changes instigated by those lawyers trained by Houston in the 1930s and ’40s. Their brilliant arguments changed the minds of skeptical jurists on issues of race and justice that had divided the nation for two centuries.

While the public at large remains mostly unaware of Houston’s great accomplishments, the convergence of Lincoln’s birthday, the anniversary of the creation of the NAACP, the decision to honor 12 civil rights legends and the imminent publication of “Accountable” remind us of the immense contribution made by leaders in our past who courageously pushed for racial equality, often at great personal and professional cost.

Before Houston was born, blacks didn’t have the right to vote, eat in restaurants, stay in hotels or drink from fountains that were not segregated by race. That has all changed. Not only do we have the right to vote, but we have elected an African American president, and 40 members of Congress who are African American. Moreover, we have CEOs, presidents of universities and leaders in the public sector that remind us of Houston’s enduring legacy.

Yet Houston’s own words also remind us that we must all be social engineers, committed to keeping African American children from dropping out of school, to ensuring more and better employment prospects and access to health care for African American adults, and to helping more African American families live in stable, healthy communities. It is the magnitude of these problems, despite our progress, that makes it imperative for each and every one of us to commit to lifting up our communities, and the children, women and men who inhabit them.

As we celebrate the presidency of President Barack Obama, let’s remember those who paved the way for him. Let’s make sure that our children and grandchildren understand that they are growing up in a world very different from the one of our youth. Let’s remind them that they must do more than reap the rewards of others’ efforts. It is their responsibility to accept the challenges of the 21st century and continue to push for the positive change needed to achieve full equality, in law and in fact.

If we can achieve so much in such a short period of time, just think about what is now within our grasp, if we don’t give up or let up.

Charles J. Ogletree Jr. is the executive director of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School. His most recent book is “When Law Fails: Making Sense of Miscarriages of Justice,” published in January by NYU Press.