One year in, Health Commission efforts towards youth mental health aim for sustainability, broad network of support

City efforts to address youth mental health challenges have reached thousands of Boston’s young people, according to the Boston Public Health Commission.

That work, which was first announced by the BPHC in March 2024, aims to use $21 million over the course of five years to tackle youth mental health needs across a spectrum of solutions.

“People often say, ‘It takes a village to raise a child.’ We’re building that village by providing real, meaningful support to the caring adults in young people’s lives — giving them the tools they need so no one has to face youth mental health challenges alone,” said Samara Grossman, director of the health commission’s Center for Behavioral Health and Wellness, in a statement.

Those efforts, in partnership with Boston Public Schools, include teaching basic behavioral health skills to non-clinical staff, and working to adjust school policies to better serve the mental health of students. Partnerships with the University of Massachusetts Boston and Franciscan Children’s support the training of a larger and more diverse cohort of mental health clinicians to work with students and Boston youth.

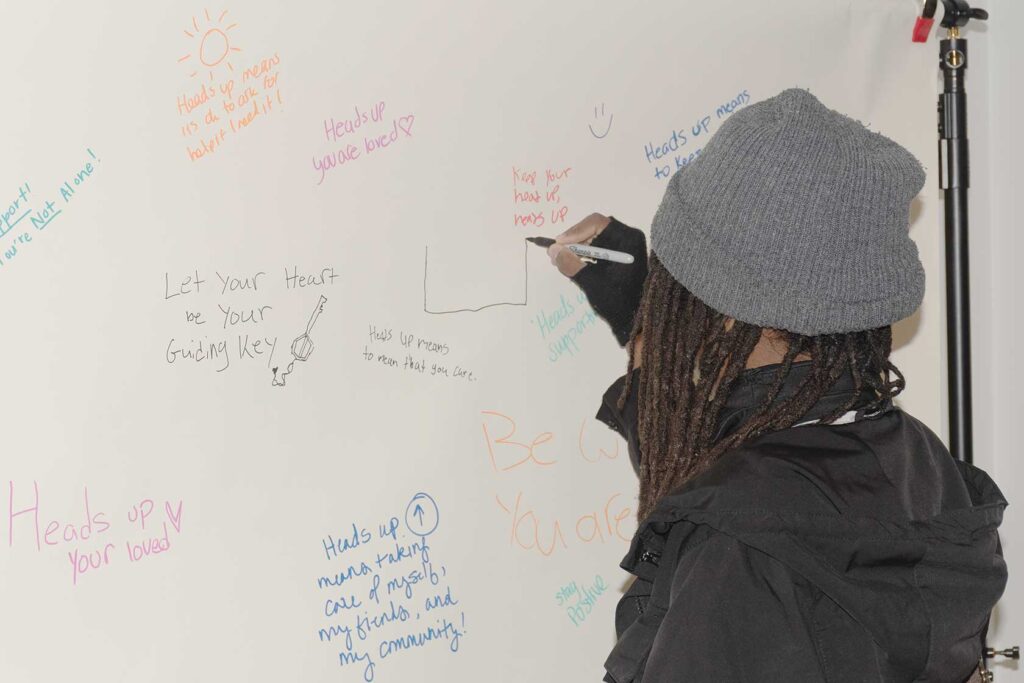

The initiatives are also focused on engaging with the city’s young people about their mental health. Funding includes support for the health commission’s Boston Area Health Education Center, which trains students in careers in health education, including behavioral health. And the commission last year launched its Heads Ups initiative, a campaign aimed at encouraging young people to talk about their mental health.

Over the course of its first year, the program has supported the training, licensure support and career placement of over 300 mental health practitioners and worked with nearly 1,100 youth-facing staff from city departments, Boston Public Schools and community-based organizations.

According to a 2024 report from the Boston Public Health Commission, young people in the city saw a significant increase in sadness, hopelessness and anxiety, with 40% of BPS students reporting feeling persistent sadness and hopelessness.

The city’s work may help provide new guidance for others working in the space about how best to serve students, said Dr. Randi Schuster, founding director of the Mass General Center for School Behavioral Health, who is not associated with the BPHC efforts.

That center, part of Mass General’s Department of Psychiatry, launched in February.

“I was thrilled to see that this work is underway,” said Schuster, who is “eager to learn” from the health commission’s work and early findings.

Certain elements of the work might be particularly promising. The commission’s efforts to expand who youth can rely on to support their behavioral health is not only an effective solution, but a critical one, Schuster said.

A new study from Schuster’s Center for School Behavioral Health at Mass General, published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry on June 25, found that mental health staffing at schools can help address so-called “neighborhood deprivation,” factors in disadvantaged communities that can leave youth at greater risk of experiencing mental health conditions.

According to the study, higher ratios of behavioral health staff to students in schools could counteract the trends of higher rates of neighborhood deprivation being associated with higher occurrences of psychiatric symptoms.

“The more of these individuals that are equipped with basic behavioral health prevention and intervention tools, the more of these individuals that are available to kids, the stronger the protective effect that we saw,” Schuster said.

A key part of that, said Teresa Vargas, the study’s lead author, is its lens of considering behavioral health staff beyond traditional clinical roles.

“Something that can be really important, if you’re thinking of mental health prevention and intervention, is people actually being able to identify that something is wrong or potentially catching something that might be off, like you know this kid might need help,” Vargas said. “The staff that we included in our definition includes a broader behavioral workforce that are all equipped to do that.”

It’s an approach that Schuster said can help not only better serve students but also address access while the youth behavioral health workforce faces an ongoing shortage of staff.

For the Boston Public Health Commission, those efforts to expand support beyond strictly clinical roles include grant funding targeted at training youth-facing roles in BPS and in the city at large to have better skills to work with and support the behavioral health of the city’s young people. Another $1 million is aimed at training staff at community-based organizations, according to the March 2024 press release announcing the initiatives.

“The sites that enroll in this program learn how to give back to their own staff, across the entire staff as far as possible, so that they understand youth mental health, when to reach out for more help, when to really listen to youth more deeply and create a safe space for them,” Grossman said in an interview.

Jenna Parafinczuk, Boston Public Schools director of social work, said it has been an important step to help connect with students in BPS schools, and a way to avoid putting more work on teachers.

“We know that all kids don’t feel a connection to just a teacher, that there could be a welcoming custodian every day — which we have — that could be the person who they feel like they want to talk to,” she said.

Efforts under the initiatives are also aimed at diversifying the city’s behavioral health workforce. $2.5 million, according to the March 2024 press release, is being directed toward programming at the University of Massachusetts Boston to train youth-facing behavioral health practitioners. As part of that program — which includes offering financial support, internship stipends, mentorship and additional resources — students must commit to working in Boston for three years after graduation.

“That is tied to being accepted into the program,” Grossman said. “So, we were carefully thinking about how we make sure that those that we’ve invested in give back to Boston communities.”

Greater diversity can produce better outcomes, Schuster said, and cultural representation can better support kids to be able to draw on shared identity with those behavioral health staff. Increasing those numbers, too, can bolster a workforce that doesn’t currently have enough staff to match needs.

“I think creating equitable pipelines for more diverse individuals from varied backgrounds to be able to enter and sustain work in that field is just critically important for the future of behavioral health, as well as meets the immediate need of boots on the ground in schools,” Schuster said.

And just knowing those staff exist can be helpful, Grossman said.

“It can be really helpful to see and uplift people that look like you or speak your language or have some of your same identities in the behavioral health workforce,” she said. “Even if you yourself don’t go see those clinicians personally, knowing that they’re there and supporting you and reflecting your community can be very powerful.”

Grossman said that, for the Boston Public Health Commission, a priority in all the work is sustainability, that even beyond the five years the work is slated for, the impact will continue.

That priority, she said, can be seen in the UMass Boston partnership’s requirement to work in Boston for three years after completion of the program. Similarly, capacity-building work done in Boston Public Schools to train a wider array of staff is being done with priority on not just teaching individuals. Instead, that work, through a company called Flourish Agenda, is aimed at shifting policies at the 10 schools and training the staff not just to have the skills themselves, but to be able to teach them to others within the organization.

“The capacity building work that we have been supporting is sustainable by nature with the train-the-trainer approach, so that we know that iteratively, the trainings that we’ve invested in now will be able to be brought back out across those community organizations that have enrolled in the program for years to come,” Grossman said.

For Parafinczuk, at Boston Public Schools, that also means looking for additional funding to keep the programs they’ve started running. She said that both the grant funding the work with Flourish Agenda and an expansion of the Children’s Wellness Initiative — a partnership with Franciscan Children’s hospital, that places clinicians across BPS — are slated to end in 2026.

“I think our main goal will be, over this year, to implement to ensure we have metrics that we can share out and then look for more funding to continue in more schools, which I know can be a struggle, but I think we have the commitment,” Parafinczuk said.

She said that BPS is also partnering with Boston College over the next year to identify what better mental health supports can look like in BPS and how to make those efforts sustainable.

But work in the space can also be improved by moving focus away from just funding programs on grants to find longer-lasting solutions, Schuster said.

“At the end of the day, this comes down to dollars and cents,” she said. “What we cannot afford to do anymore is for supports within communities to come and go with grant funding.”

Schuster pointed to what she said is a need to move away from traditional models that often rely on grant funding, where researchers enter a community, try out a solution, and then pull support away when the funding is up.

Financial sustainability is a priority for her and her team, she said, which means looking for solutions like state funding or reimbursement through Medicaid.

“What are the ways that these great ideas that we are thinking on stay alive after this time limited funding mechanism ends?” she asked.

And shifting models can also mean getting work done sooner. Schuster said she and Vargas both come from academic backgrounds where the timeline from developing an idea for a solution to putting it in practice and reporting out results can take years or a decade.

“I think we’re in a time where that’s just not acceptable,” Schuster said. “The time is now to be making changes in schools.”