Ngugi wa Thiong’o stands as a towering figure in African literature, a writer whose prolific career has been inextricably linked with the political and cultural struggles of his native Kenya and the broader African continent. Born James Ngugi in 1938 in Kamiriithu, Kenya, his journey from colonial subject to a vocal advocate for linguistic and cultural liberation has shaped a body of work that is as intellectually rigorous as it is deeply personal. Ngugi’s essays, novels, and plays are not merely narratives; they are powerful critiques of colonialism, neo-colonialism, and the enduring legacy of linguistic imperialism, advocating an African-centered perspective in both thought and expression.

Ngugi’s early life was marked by the Mau Mau uprising, a pivotal anti-colonial struggle that profoundly influenced his nascent political consciousness and literary themes. His education, initially in mission schools and later at Makerere University in Uganda and the University of Leeds in England, exposed him to both Western literary traditions and the burgeoning anti-colonial discourse. This dual exposure provided him with the tools to dissect and challenge the very structures of power he had experienced.

His early novels, written in English, such as “Weep Not, Child” (1964) and “The River Between” (1965), explored the devastating impact of colonialism on Kenyan society, focusing on themes of land alienation, cultural clash, and the psychological toll of oppression. These works established him as a significant voice, capable of articulating the complexities of a nation grappling with its identity in the aftermath of British rule.

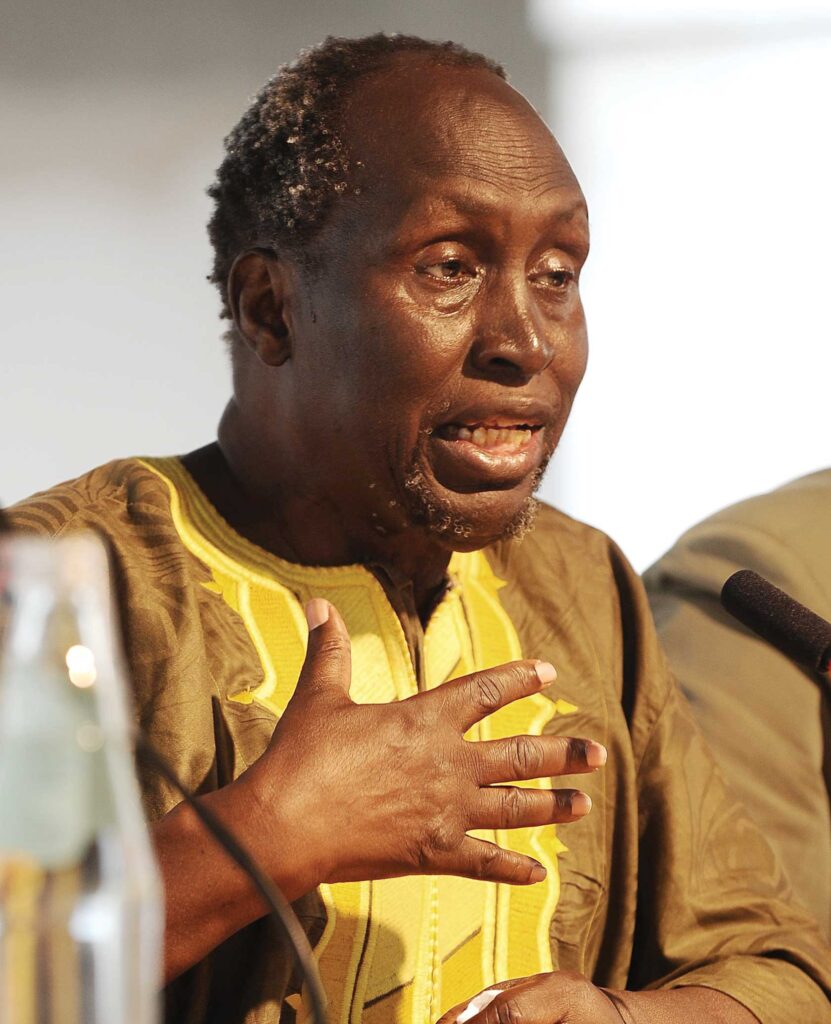

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o reading at the Library of Congress in 2019. PHOTO: Shawn Miller/Library of Congress

However, it was Ngugi’s radical shift in the late 1970s that cemented his unique place in literary history. Dissatisfied with the continued dominance of European languages in African literature and education, he made the momentous decision to write exclusively in Gikuyu, his mother tongue, and later in Swahili. This decision, articulated forcefully in his seminal work “Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature” (1986), was not merely a linguistic preference but a profound political act. He argued that language is not just a means of communication but a carrier of culture, history and identity.

To write in African languages was, for Ngugi, an act of reclaiming agency, fostering cultural pride, and ensuring that African stories reached and resonated with the very people whose experiences they depicted. This commitment led to works like “Caitaani Mutharaba-ini” (Devil on the Cross, 1980), written while he was imprisoned without trial by the Kenyan government for his politically charged community theatre work.

Ngugi’s literary themes consistently revolve around the struggle for liberation — from colonial shackles, from neo-colonial exploitation, and from mental servitude. He meticulously unpacks the mechanisms of oppression, from the economic exploitation of multinational corporations to the ideological subjugation perpetuated through education and media. His narratives often feature protagonists who awaken to political consciousness, challenging the status quo and striving for a more just society.

The concept of betrayal is also central to his work, exploring how African elites, often educated in Western systems, can become complicit in the continued exploitation of their own people. Yet, amid the critique, there is always a resilient thread of hope and the unwavering belief in the power of collective action and cultural reclamation.

The impact of Ngugi wa Thiong’o extends far beyond the literary realm. His advocacy for African languages has spurred academic and cultural movements across the continent, encouraging scholars and writers to embrace indigenous linguistic traditions. His experiences with political persecution — including imprisonment, exile, and the tragic attack on his family — have made him a symbol of courage and resistance against authoritarian regimes. He has consistently used his platform to speak out against injustice, whether in Kenya or globally, embodying the role of the public intellectual committed to social transformation.

As a professor and public intellectual, he taught at prestigious universities, including Yale, NYU, and the University of Nairobi. His essays, lectures, and interviews continue to inspire scholars, writers, and activists across the globe. He has been nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature numerous times, with many viewing him as a deserving laureate whose contributions transcend national and linguistic boundaries. This includes his 2016 short story, “The Upright Revolution: Or Why Humans Walk Upright,” which has been translated into more than 100 languages and is the most translated story in African literature.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o was more than just a writer; he was a cultural revolutionary whose pen has served as a powerful weapon in the fight for African liberation. His unwavering commitment to writing in African languages, his incisive critiques of power, and his profound exploration of identity and resistance have left an indelible mark on global literature and post-colonial thought.

Through his enduring legacy, Ngugi reminds us that true freedom encompasses not only political independence but also the liberation of the mind and the reclamation of one’s cultural heritage. He once said, “Your own actions are a better mirror of your life than the actions of all your enemies put together.” Today his work continues to inspire new generations to decolonize their minds and to recognize the inherent power and beauty of their own voices.