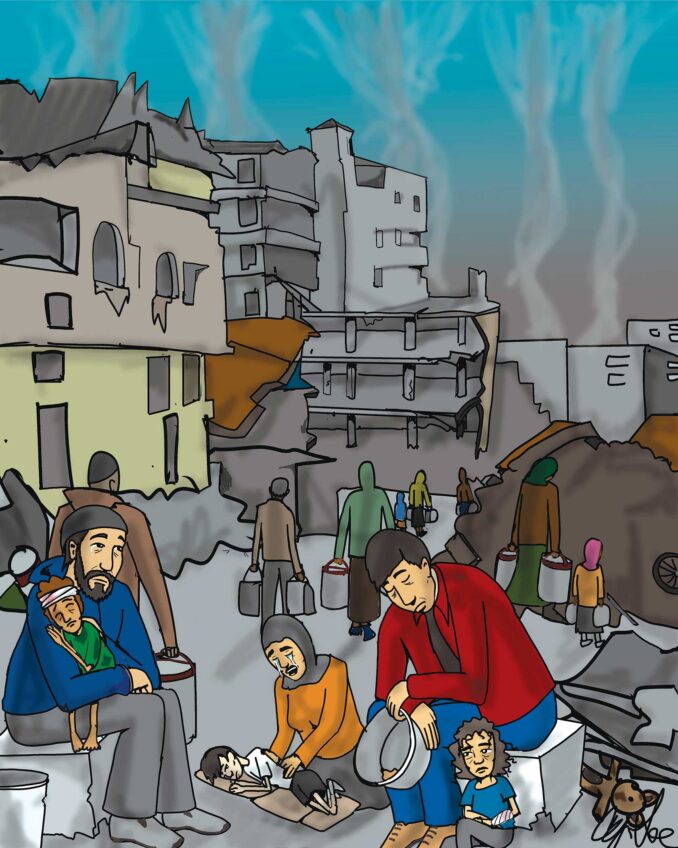

Without school-based support, Black students face greater emotional distress, academic declines, and rising suicide risks.

Research shows that suicide rates among Black youth have climbed by nearly 37% over the past five years, with Black teens now reporting higher attempt rates than their white and Hispanic peers. At the same time, Black and Native American students are 1.3 times more likely than white students to attend schools with a police officer — but no school mental health counselor.

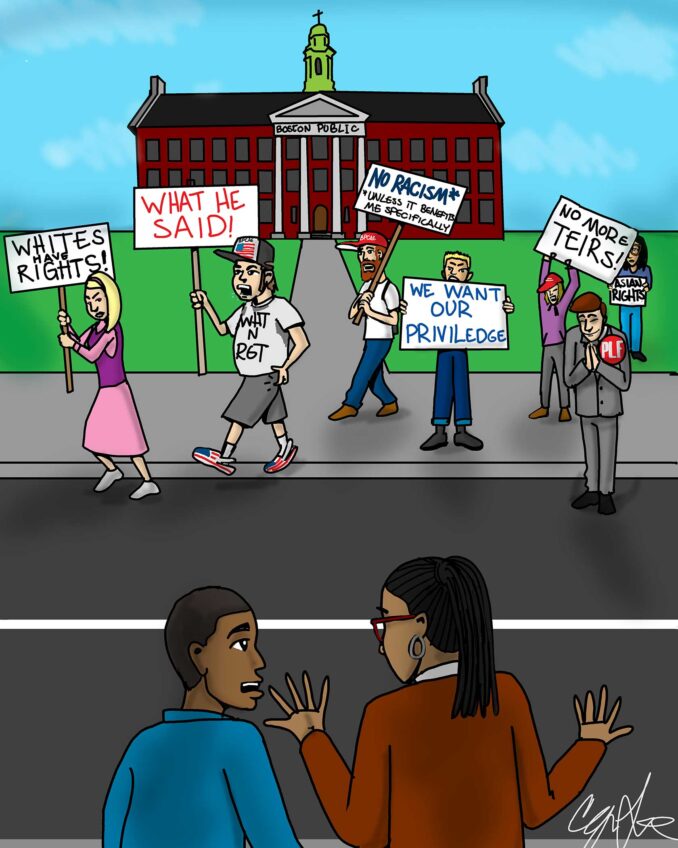

So, educators, families, and education advocates were alarmed when, earlier this month, the Trump administration slashed $1 billion in federal funding for school-based mental health programs.

The funds, created under the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, were intended to help schools address the growing youth mental health crisis. With this support now cut, Black students, especially, may face the steepest of consequences.

“Just when you think they can’t go lower, they find another way,” said Dr. Sonya Douglass, professor of education leadership and founding director of the Black Education Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University. “It flies directly in the face of the mental health challenges that this very administration helped create.”

Douglass, a nationally recognized education equity expert, says the White House’s move will at best deepen disparities in support, school safety and access to wellness-centered learning environments. At worst, she says, it increases Black students’ risk of significant psychological harm — including suicide.

Black students are already at risk

Even with counselors present, access remains limited. According to a 2024 USC study, only 29% of Black families report having access to mental health services in their child’s school.

“The fact that our children are dying — and still losing access to mental health resources — should be seen as a national crisis,” Douglass said.

The crisis, however, has been building for years.

Data consistently shows that Black students are routinely exposed to racial discrimination, disproportionate rates of school-based discipline, and school environments that ignore their social-emotional needs. In her research, Douglass has repeatedly pointed out that schools were never designed to meet the needs of Black children in the first place.

“Whether it’s a curriculum that doesn’t reflect who they are or schools that are no longer physically or emotionally safe, the entire environment becomes harmful,” she said. “And if you pile trauma on top of trauma, eventually something breaks.”

Education without care is dangerous

Defenders of the funding cut argue that it gives local districts more control over how to allocate resources. But Douglass calls that logic shortsighted — and dangerous.

“President Donald Trump and like-minded conservatives understand the stakes; that’s why they fight so hard over books, curriculum, and control of schools,” she said. “We have to match that energy. We must demand that our children are taught their history, treated with respect and given the high-quality education they deserve.”

Douglass warns that without public investment in education and mental health, the country risks becoming, in her words, “a Third-world country,” where Black children are left without the support they need to thrive.

“When the federal government steps back, it just depends on where you live — and who holds local power,” Douglass said. “Civil rights protections have always been needed to ensure that students in marginalized communities aren’t left behind. Without federal oversight, we know those resources won’t reach the children who need them.”

Protecting the mind, body and spirit

Despite the federal rollback, Douglass says Black communities cannot afford to wait for rescue. At the Black Education Research Center, she and her team are working to build a policy and advocacy arm to support educators, parents and students navigating this moment.

“We cannot put the fate of our children in the hands of the federal government,” she said. “We must protect their minds, bodies and spirits. That means being thoughtful about how they’re educated, how they’re supported and how they’re loved. We can’t wait — we have to build now.”

Quintessa Williams is an education reporter for Word in Black. She has also written for Travel Noire, Medium, and The Root covering topics in social justice, Black Lives Matter, racism, and womanism.