As Massachusetts aims to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions and meet 2050 net-zero goals, the state’s high schoolers are being targeted as a key group to fill pending gaps in the state’s clean energy workforce.

A new state curriculum, launched by the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center, April 15, aims to reach more of those students and show them the wide range of careers that exist in the sector.

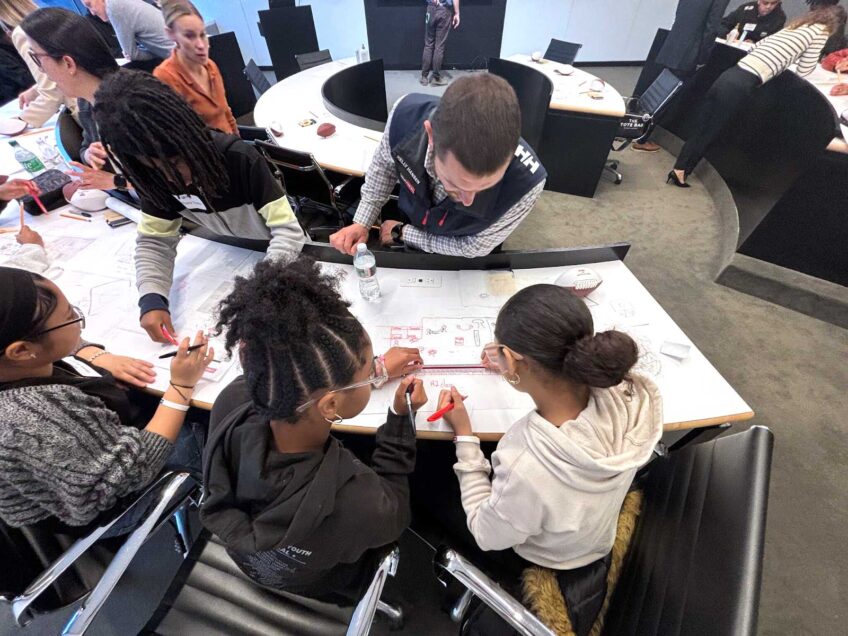

“We believe deeply in the potential of young people to lead the charge in solving our climate crisis,” said Emily Reichert, CEO of the MassCEC, at a launch event in Newton that featured a speaking panel with employers in the industry and hands-on activities for a cohort of high school students who attended.

The curriculum is intended to bring more faces — including diverse ones — into the workforce. It’s a step that the MassCEC said is necessary to close pending gaps in the workforce that could hinder its longer-term climate goals.

According to the Clean Energy Center’s 2023 Clean Energy Workforce Needs Assessment, the industry will need about 34,000 workers in the renewable energy sector. In 2022, the report found that there were 26,226.

The curriculum — which has 18 units ranging from the basics of understanding and combatting climate change to specific technologies like solar, geothermal, wind and more efficient buildings —targets high schoolers with lessons, real-world case studies and stories from diverse professionals across the state.

A student from CityLab High School in Revere tries stripping wire to learn about the job of solar panel electricians at a launch

event for the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center’s new clean energy curriculum for high schoolers, April 15. The curriculum aims to expose high school students to information about the array of careers in the clean energy sector. PHOTO: AVERY BLEICHFELD

Since January, teachers in Massachusetts have been piloting the program, with more set to begin implementation in the 2025-2026 school year, Reichert said.

Covering that wide range of topics shows the diversity of options available in a clean energy career. Cynthia Brown, CEO at Innovation, Workforce & Learning Energy, which helped develop the curriculum, said it features 50 different professions across a wide range of skill sets and subject areas.

“It’s a lot more than what people think,” Brown said. “It’s important to show students that, depending on what your interests are, there is probably a career in this space for you.”

The program is meant to drum up that excitement for careers in the space, Reichert said.

“We know that clean energy transition isn’t just about technology,” she said. “It’s absolutely about people.”

But to build that workforce, she said, there needs to be greater education about what opportunities exist. That same workforce needs assessment found that the second most common barrier to entry into clean energy fields is a “lack of basic information about energy careers” early in education pathways.

Employers in the space like Shonte Davidson, CEO at Better Together Brain Trust, who spoke on a panel at the event, said that the possibility of bringing in a bigger workforce and a more passionate one is exciting.

“It gets me excited to know that there’s going to be a pipeline of students, that they’re going to become candidates that we can choose from,” Davidson said in an interview. “It’s going to be folks that have a real passion and a real belly flame.”

Staff at the MassCEC aren’t the only ones who see potential in fostering knowledge of clean energy careers among students. Across the Boston area, clean energy education for high schoolers is a growing focus.

At The Possible Zone, a Jamaica-Plain-based experiential learning nonprofit, a “Clean Energy Deep Dive” program connects students with hands-on learning that shows how clean energy technology works and why it can be important.

That program guides students through the process of developing a microgrid — a smaller, self-contained energy system — that uses solar panels so they can charge a cellphone.

“What’s an energy budget? How much power does your phone actually require every day? What does it feel like, physically, to produce that power?” said Jeff Branson, senior director of STEAM education and partnerships at The Possible Zone. “They have a tactile engagement with it. We want to give them real personal learning experiences.”

That hands-on perspective is a priority for other programs too, including the new MassCEC curriculum, which introduces students to a range of experiential activities, several of which — like how to strip wire for solar electricians, how to optimize the angle of a wind turbine and how to decide where to install electric vehicle chargers — were on display at the launch event.

“It makes it come alive, right?” Brown said. “I can tell you how energy works, and I can tell you, ‘Oh, okay, the wind blows and then this turbine spins,’ but having you put just even a simple blade in front of a fan, you’re like, ‘oh, yeah, I get that.’”

An earlier start in high school can keep more students involved in the learning, Branson, from The Possible Zone, said.

“What we do is pre-qualify for long-term learning,” he said. “You know, at some point in time, somewhere along the way, somebody got me interested in what became a lifelong learning path. With our early entry with our students into this, we’re hoping to establish lifelong learning trajectories.”

That can keep more of the students, many of whom come from more diverse backgrounds, in science and technology fields for longer.

Educators within science, technology, engineering and math fields often refer to a “leaky pipeline,” with women or people of color in STEM fields turning away from the subject areas, even if they had an interest in it. Getting more students involved and passionate about it early, Branson said, might keep them involved longer.

“The more engagement we can give our students early on, and the more ownership they have of it, the more likely they are to pursue lifelong learning that adds value to technical learning, their economic outcomes, our societal outcomes,” Branson said. “We’re making a long play here.”

Starting with education at a younger age can also build on skillsets younger students already have, said Salvador Pina, vice president of workforce and economic development at Roxbury Community College.

“A lot of this involves technology,” Pina said. “Students today know a lot more about technology than older adult learners do. That gives them an edge up.”

RCC is currently running a twice-a-week afterschool program with four Boston Public high schools — Madison Park Technical Vocational High School, Boston Day and Evening Academy, John D. O’Bryant School of Mathematics and Science and Dearborn STEM Academy — focused on energy auditing and energy efficiency.

That area of clean energy technology has been a focus of the school for a number of its programs, including developing a community college curriculum in collaboration with MassCEC for use across the state.

Supporters of these kinds of education programs for high schoolers point to the economic benefits jobs in clean energy fields can bring to the students and their communities.

“What we’re trying to do is get students to use these jobs as steppingstones to elevate within the clean energy industry because we know it’s a growing industry,” Pina said. “It’s really important for students to be able to explore that and if they experience a synergy with it to be able to develop a career path.”

Programs like RCC’s after-school education and the MassCEC’s new curriculum outline pathways beyond just attending college to get a two- or four-year degree.

Pina pointed to statistics that only about half of Boston Public Schools students enroll in college the first year after graduation. A report from the Boston Foundation found that in 2021 the first-year college enrollment rate was 52.6% of BPS graduates.

And that number has been dropping. In 2014, it was about 14 percentage points higher.

“If you take just the students that didn’t go to college, that’s 50% of the graduates,” Pina said. “What we’re talking about is career pathways.”

Davidson, too, said that these opportunities offer important alternatives to a college degree.

“I graduated high school in 2002, and it was like, ‘college, college, college, college,’” she said. “No one ever talked about an alternative pathway.”

Had she been presented with other options, she said, she thought she could be much happier in the first phase of her career.

The diverse range of outlooks and perspectives in the variety of programs and in the MassCEC curriculum aim to make the wide range of options more accessible to students across Massachusetts, Reichert said.

“Whether you’re in Revere or Norwood, Newton or Brockton, we want every student to be able to say, I can see myself doing that job,” she said.