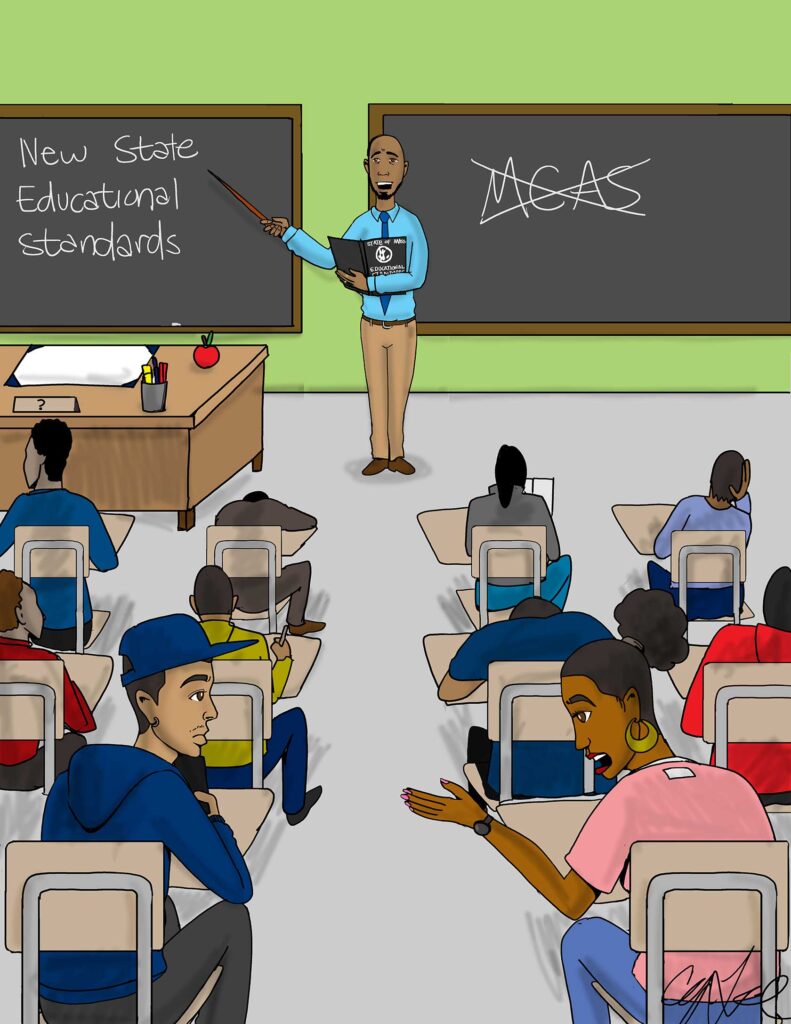

Following voters’ rejection last November of MCAS as a requirement for high school graduation, the state is proposing new standards requiring the successful completion of a designated slate of courses. Because of the state’s tradition of local control of schools, Massachusetts has never mandated which courses students have to pass to receive a diploma, leaving that decision up to school districts.

Devolving that decision to the districts made sense long ago when businesses and populations were highly localized, but not in the modern era when the conduct of business is globalized and Americans are more mobile, moving from place to place within and beyond a state’s borders.

According to the Education Commission of the States, the best source of comparative data on state educational practices, Massachusetts is one of only four states that do not mandate a full slate of courses for graduation. The others are Vermont, Pennsylvania and Colorado.

It would represent progress for Massachusetts to mandate minimum coursework for graduation, in keeping with the practice in nearly all states. The state Board of Elementary and Secondary Education is seeking feedback on a slate of mandatory courses for next year’s graduates: two years of high school English language arts; algebra I and geometry or integrated math I and II; and one year of biology, physics, chemistry or technology/engineering. Starting in 2027, graduates would have to demonstrate mastery in those courses, through a final exam, portfolio or other assessment, and in U.S. History, a one-year course.

It is difficult to compare that slate to what coursework other states require, because they measure credits or units in different ways, the Education Commission of the States notes. Suffice it to say that the proposed Massachusetts requirements look like core requirements, and rather specific ones in the case of math and science. Other states may also require social studies, foreign languages, fine art, career and technical education or physical education.

Nothing would prevent local districts from requiring coursework beyond what Massachusetts proposes to mandate, a degree of local flexibility that seems worth preserving.

There are legitimate questions to be raised about the content and the uniformity of content in the English, science and history courses that the state plans to mandate. In math, algebra then geometry is the traditional sequence, while integrated math weaves together those topics with statistics. Those courses ought to be fairly standardized by now.

The lack of uniform content and rigor of high school courses was one reason the MCAS mandate failed to close the persistent achievement gap that sees the state’s Black and Hispanic students lagging their white and Asian peers. The MCAS mandate was equivalent to checking for quality of the output, the graduate, without assuring the inputs — the courses they take — were the same and of the same quality. No manufacturing business that functioned that way would succeed, doing quality control only at the end of the line.

For the two years of English, some relevant questions are: How much writing will students have to do? How rigorous and diverse will the literature they read be? These courses need to impart to students the ability to communicate with the written word and think critically and analytically about what they read.

Science courses like biology, physics and chemistry might seem to be standardized, and to a certain extent they are. But will all students have access to laboratories and lab equipment? Will they be required to conduct experiments, learning the scientific method in a hands-on way? Perhaps most importantly, will their teachers be certified to teach the science courses?

In the upcoming requirement for a U.S. History course, the central question in these times is whether the courses will teach the honest truth about the country’s history of racism, from the wording of the Constitution onward, despite the attempt of the current administration in Washington to whitewash that history? Will it teach the racist origin of the country’s first immigration law — the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882? And the persistence of racial code words in political campaigns?

As things stand now, there is no way to know what the content and quality of the mandated courses will be. That’s because while the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education produces curriculum frameworks, school districts do not have to follow or even use them.

It will make sense for the state to require uniformity in the curriculum of the courses mandated for graduation. That is the only way parents, taxpayers and businesses can have a reasonable expectation of something like uniform results. Traditional local control of curriculum needs to yield not just on the courses required to graduate, but also the content of those courses. If the state’s businesses leaders want assurance that a diploma represents a certain standard of quality, they ought to get behind this limited reduction in local control.

A word about the proposed requirement to demonstrate mastery in the mandated courses in the future. Here’s hoping the state’s school districts get creative, get with 21st century and entertain the possibility of students demonstrating their mastery, say, by producing a multimedia presentation instead of taking a final exam. The students of today are tech-savvy visual learners. Tap into that.

Through April 4, the state board of education is accepting public comment on its proposed changes to graduation standards. You can make your comments here: Competency Determination

Black and Hispanic educators, parents, lawmakers and students need to make their voices heard. As the Banner editorialized, getting rid of MCAS as a graduation requirement was a good thing. The voices of representatives of the students that state’s schools have left behind need to make sure the alternative is indeed better.

Responding to the state proposals is only step one. The course requirements are intended to be an interim measure while a graduation council that Gov. Maura Healey established formulates standards for the long term. The council is scheduled to release its preliminary findings by Dec. 1, and its final recommendations by summer of next year. The only way we insure the best outcome is if we make our request known and stay vigilant and engaged.

Ronald Mitchell

Editor and Publisher, Bay State Banner