New perspectives on Black History from WriteBoston’s Teens In Print program — week 3

This Black History Month, the Banner is teaming up with WriteBoston’s Teens In Print program, highlighting young voices of color. Each week, we will feature the work of three new students, who will deliver their perspectives on Black History and what it means to them.

On our names and their traces

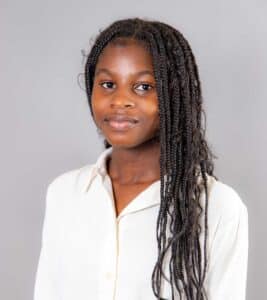

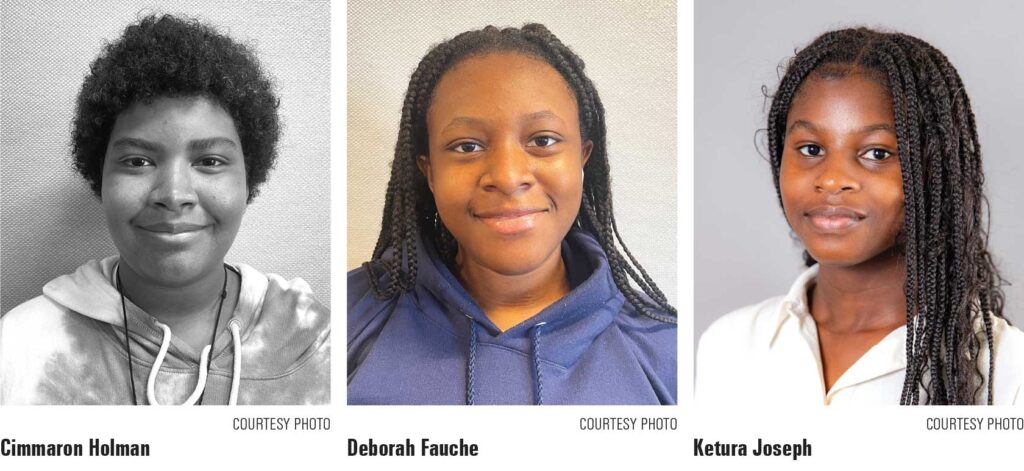

By Cimmaron Holman

Names are the pinnacles of cultures, they can really mean the world to a person and/or family. This is something that inspired me and I wanted to write about it. I thought more on the topic, and I realize it resonated with me a lot because I’m a person of color who happens to have a pretty unique name and I know people of color are often ostracized for having “ghetto names.” And while, thankfully, my name has never been called that, it still had me wondering why our names are so unique.

I did some research and saw there was a rumor that during slave times enslaved people would name their children such unique names so that if ever separated they would be able to reunite because their name would be so unique. Then, hearing it would allow them to find their child. But this isn’t as cut and dry as I just described. I looked for sources to back this claim up, yet I found none that were credible. So I went to a professional in this field. And what I found was something that I never even imagined to be.

I interviewed Ms. Chastidy Rubin, who has been a history teacher at Brooke High School for four years. She has two degrees in history and history education, with a concentration in marginalized group’s interpretations of U.S. history. She is currently teaching world history and AP African American studies. This is what I learned from that interview. Black history is something that is mainly written down by other people, history that is often valued in the West. In America, history is written down and documented throughout time periods, which contrasts with traditional African history, which is usually taught through oral tradition.

As we spoke more on the topic of names for enslaved people, I found out that Ms. Rubin herself has a hard time finding the idea of Black people naming their kids unique names during enslaved times. There were two possible reasons for this, she stated. Reason number one is that simply during the time no one cared to write it down and as time moved forward and progressed this historical fact died along in the past. Reason two is simply the way and the fashion African American people were naming themselves during enslavement had no correlation.

We looked at the naming records of enslaved people in South Carolina. As we looked together, we saw that there were other naming patterns that were pointed out by the author of this article. One pattern that was pointed out was pretty similar to the original idea for this article — that it was an act of resistance. Now it didn’t show itself in the form of naming unique names to be able to identify their children if ever lost, it showed itself in a very different manner. They did it as a way to show resistance to the forced assimilation put upon them by the white colonizers. By naming their children after their home tribes, it allowed them to keep and maintain their identity.

Another pattern that appeared was the large number of names that were Christian. This was done to help give their children the best opportunities in life that they could, while even still being enslaved. It was done as an act of survival by putting their children in this more American setting to help give them the best life possible.

One thing that Ms. Rubin helped me find is the reason Black people might be called Shaniqua and Ashanti and all these other names of uniqueness actually started during the Black Power Movement. It’s due to the wanting of pride for one’s culture, which African American people were simply robbed of by being taken from their homeland, brought to a new country and assimilated through years upon years. It then manifested itself as people started to name their children names that connect to African roots, for example, Ashanti, which is named after an African tribe and kingdom to which some people might trace their lineage back, as a way to have that culture that they were robbed of and try to scrape up any little bits that they can. From here on, the name Ashanti can easily be played on and twisted and turned to become its own unique variation of the name, which is why we have so many unique variations of it.

So the next time you hear a name of a person of color, don’t say, “That’s a ghetto name.” Think of the history behind it, think of the struggles, the heartache, and never ending fighting. Names aren’t just names. They have history, they have meaning, and they have power. So, next time you hear Ashanti, Jamal or Shaniqua just remember that it’s someone’s history that has meaning to someone, and that’s someone’s power.

Cimmaron is a student at Brooke High School and has been a reporter at Teens in Print since 8th grade. He explores various forms of journalism, including podcasts, print, and public relations.

Social media: My Black history teacher

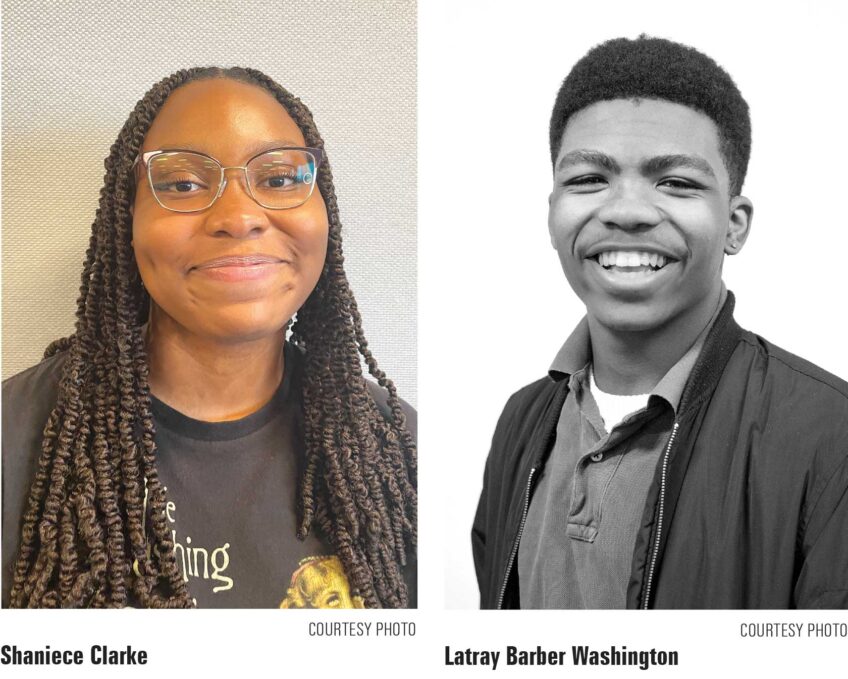

By Deborah Fauche

Fun fact: Teaching Black history is not federally required in the U.S. According to The 74, an education news site, only 12 states — Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Washington — mandate Black history in K-12 public schools. As a result, many students receive only a limited understanding of Black history, leaving them in the dark about key truths of American history. This gap in education impacts their perspectives, opinions and actions for the rest of their lives.

While Black History Month is widely recognized, it often focuses on honoring historical figures who paved the way for racial equality. However, Black history is still being made every day. With the rise of social media, influencers and educators are bringing greater awareness to Black culture, history, and current contributions. Platforms like TikTok and Instagram have created spaces for people to learn about Black history when their schools or communities may not provide that opportunity. Social media not only helps us celebrate the past but also shines a light on the present achievements of Black excellence.

On average, people spend about two hours and 23 minutes daily on social media, with some using it for as long as 8 to 10 hours. While many see it solely as a tool for entertainment and communication, social media is also a powerful space for education and community building. It allows people to share knowledge on a wide range of topics with diverse audiences. This is especially important for celebrating Black History Month. Many influencers and authors, such as Rachel Elizabeth Cargle and Ibram X. Kendi, use their platforms to educate people about Black history and its continued impact on society today.

For me, social media has become my Black history teacher. In school, Black History Month discussions often focus on historical leaders like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks — figures who played crucial roles in the Civil Rights Movement. While it’s important to honor those who paved the way, it’s just as essential to recognize Black excellence in today’s world. In every industry — business, entertainment, literature, and beyond — Black individuals continue to break barriers and redefine success.

Social media spotlights modern-day changemakers like poet Amanda Gorman and activist Alicia Garza, alongside influential Black actors like Michael B. Jordan and Angela Bassett. Musicians like Kendrick Lamar, with his symbolic Super Bowl halftime show, and Beyoncé, the first Black woman in 33 years to win Album of the Year at the Grammys, are pushing Black culture forward on global stages. Platforms like The Shade Room Teens provide a space for young people to stay informed about Black excellence and cultural achievements.

Through social media, I’ve also discovered the rich Black history within my own community. I’ve learned about activists like Melnea Cass, Elma Lewis and Mel King — figures who have shaped my city in profound ways. Social media has also introduced me to local events celebrating Black history, from museum exhibitions to sports initiatives and educational programs. It’s been eye-opening to realize how many opportunities exist for me and my friends to engage more deeply with our culture.

Black history should be celebrated year-round, not just in February. Thanks to social media, this ongoing celebration is possible. It serves as a bridge between the past and the present, allowing Black excellence to be recognized, appreciated and shared with the world — every single day.

Deborah is a junior at Brooke High School who loves reading and watching drama series. In the future, she hopes to become either an author or a nurse.

The impact of colonialism: Understanding Africa’s history and its lasting effects

By Ketura Joseph

During meals, I often heard the phrase, “Don’t waste your food because there are children starving in Africa.” But why is that the most common narrative about Africa? Why is the continent so often associated with poverty and struggle? While there is no single answer, I believe colonialism is a major reason why many African — and some Asian — countries continue to face economic hardship today.

Whitewashing colonialism: myths and realities

Nigel Biggar, former director of the MacDonald Centre for Theology, Ethics, and Public Life, led a research project called Ethics and Empire, which aimed to assess the morality of imperialism. Biggar attempted to justify colonial rule, citing examples such as Britain’s abolition of the Atlantic slave trade in 1807 and the fact that Black Africans were granted voting rights in 1892 — 17 years before African Americans men were given the right to vote.

However, this selective framing ignores the deeper harm of colonial rule. The Cape Franchise and Ballot Act, for example, may have allowed a “non-racial franchise,” but it also raised the property qualification for voting from £25 to £75 — effectively disenfranchising many Black South Africans. As historian Sabelo

Ndlovu-Gatsheni puts it in Moral Evil, Economic Good, “The fact is the African struggles were not undertaken for a trinket like getting voting rights under colonialism.” Imperialism didn’t just limit political rights; it reshaped entire economies and societies to benefit European powers at the expense of the colonized.

What Africa could have been: The devastation of the Berlin Conference

Had imperialism never happened, Africa could have taken a very different path. Before European intervention, various African kingdoms, such as Mali, Songhai and Great Zimbabwe, thrived with sophisticated trade networks, governance systems, and cultural achievements. The Berlin Conference of 1885, however, marked a turning point. European nations carved up Africa without regard for existing political ties or rivalries. This disregard led to artificial borders, internal conflicts, and the forced restructuring of African economies to serve European interests.

Many African and Latin American countries now have cash crop economies, where the bulk of their GDP relies on a single commodity, such as bananas or vanilla beans. This dependency makes them vulnerable to economic fluctuations, further limiting their growth. Imperialist economic structures continue to push many people to migrate to countries like the U.S. in search of stability, ironically, in nations that profited from their historical exploitation.

The lasting effects of imperialism: The wealth gap in Boston

The effects of imperialism extend far beyond Africa and can be seen in places like Boston through the racial wealth gap. According to The Boston Globe, a study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston found that the average net worth of Black households in Greater Boston is just $8, compared to $247,000 for white households. That disparity is staggering.

One major factor is homeownership. After World War II, the GI Bill helped millions of veterans purchase homes, allowing them to build wealth that could be passed down to future generations. However, discriminatory policies like redlining denied many Black veterans access to these benefits. The GI Bill could have been the “40 acres and a mule” that America never provided as reparations for slavery, but instead, it reinforced racial economic disparities. The racial wealth gap today is not just about individual choices; it is the result of systemic oppression that dates back to colonialism and the economic systems it put in place.

The importance of knowing your history

In many schools, Black history is taught primarily through the lens of struggle. While resilience is crucial to understand, so is the richness of African cultures, traditions, and successes. Africa is a vast continent with diverse languages, histories, and innovations that deserve better representation in media and education.

For me, learning about a broader history — beyond suffering — has strengthened my pride in my identity, my roots, and even my relationship with my hair. Knowledge is power, and understanding history is essential to breaking cycles of misinformation and reclaiming narratives about Africa and its people.

Ketura Joseph is currently a junior at Brooke High School. Ketura has been writing Teens in Print for three years. Her favorite types of articles to write include op-eds and reviews. Ketura is currently a newsroom report for Teens in Print.