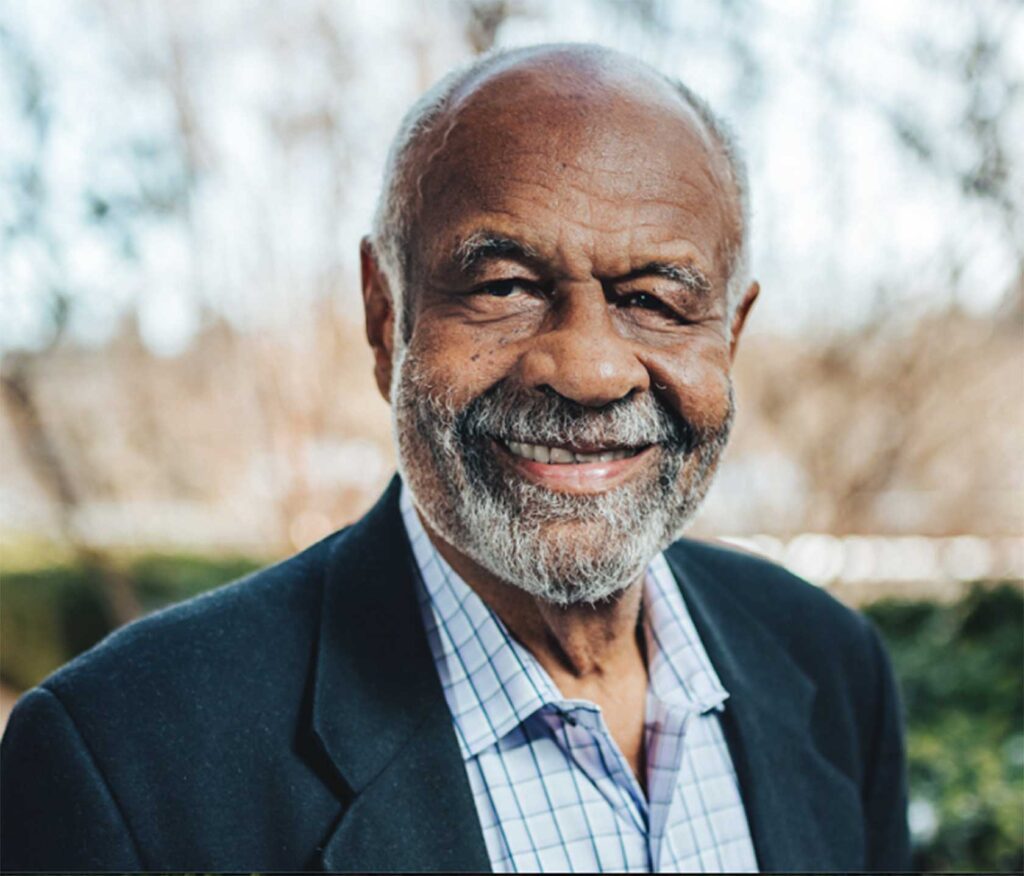

Fletcher Houston Wiley, known citywide as “Flash” Wiley, an attorney, civic leader and a leading member of Boston’s business community, died on Feb. 7 at 82.

He will be remembered as one of the founders of Fitch, Wiley, Richlin & Tourse, then-touted as the largest minority-owned law firm in New England; as the first Black chairman of the Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce; and as a trusted adviser to top city and state elected officials.

Flash Wiley was born in Chicago on Nov. 29, 1942, the only child of Mildred Norton Fleming, a beautician, and Fletcher Wiley, a janitor. His parents divorced when he was four; he and his mother moved to Indianapolis to live with his maternal grandmother, Mama Florence, a nurse at an all-Black high school.

Wiley attended a segregated elementary school. In 1953, he was selected as a charter member of the “Gifted Child Program” by the Indianapolis Public Schools, becoming one of two Blacks in an otherwise all-white program for gifted children.

After graduating from the integrated Shortridge High School in 1960, he was recruited by and entered the United States Air Force Academy. There, he became its first Black football player — his athletic prowess earning him the lifelong nickname “Flash” — and the school’s fifth Black graduate in 1965. As the Academy’s first Black Fulbright Scholar, Wiley continued his studies at L’Institut des Etudes Politiques at the University of Paris in France.

Following his service as a captain in the U.S. Air Force, Wiley’s pursuit of higher education took him to Boston, where he earned a J.D. from Harvard Law School and a master’s in public policy from the John F. Kennedy School of Government in 1974. He was also a founding member of the Black Alumni Associations of both Harvard Law School and the Kennedy School.

Wiley later worked for the state attorney general’s office and the federal Department of Health, Education and Welfare and was a founding partner in the firm Budd Reilly & Wiley, concentrating on corporate and commercial law and small business development, among other areas.

“Flash Wiley was as comfortable on Humboldt Avenue as he was on High Street,” said his lifelong friend Richard Taylor. “I say that because he was a founder of Crispus Attucks Day Care on Humboldt Avenue. Many people don’t know that.”

Additionally, the Wileys, the Jacksons and the Taylors began a Black homeownership renaissance on Fort Hill in the ’70s. “We were able to purchase brownstones that were in tax foreclosure and renovate them for homeownership and we built two-family townhouses on Fort Avenue as well as Fountain Hill,” said Taylor.

Wiley created and chaired the Governor’s Commission on Minority Business Development in 1984.

In 1991, Wiley cofounded Fitch, Wiley, Richlin & Tourse — a merger of the 11-lawyer firm Fitch, Milller & Tourse, established in 1981, and the 11-lawyer firm Wiley & Richlin, established in 1979. The firm billed itself as New England’s largest minority law firm. Wiley left the firm two years later and joined Goldstein & Manello in September 1993.

On the evening of May 11, 1994, Wiley assumed leadership of the Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce as the first Black chairperson. In his acceptance speech that evening at the Sheraton Boston Hotel, he vowed to do his “best to represent and advance the common interest of us all,” and added, “You can be certain that the special bond and sensitivity I feel for my business and ethnic roots will not be forgotten.”

Wiley was also a supporter of affirmative action. “But for affirmative action, I would not be where I am today,” he said in 1992. “I believe that affirmative action opens doors. Sometimes it opens doors to some by having to close doors to others. If you have an all-white police or firefighting force, if there are finite slots, and you want to have integration, then somebody’s got to lose an opportunity, no matter how qualified, until past wrongs are righted.”

Regarding affirmative action in Massachusetts, Wiley in June 1995 said, “If everything in the Commonwealth worked perfectly, and we [minority businesses] got 10%, that still leaves 90% for the guys who have been getting 100% all along. And they ought to be able to get by on that.”

Wiley left Goldstein & Manello in 1996 and joined PRWT Services, Inc. of Philadelphia as vice president and general counsel. Before he retired from employment with PRWT in 2008, he helped build the company into one of the nation’s largest minority-owned businesses and Black Enterprise Magazine’s 2009 “Company of the Year.”

As a board member of the Dimock Center, Wiley, along with Clayton Turnbull, led a resurgence of “Steppin’ Out,” rejuvenating the fundraising event, said Taylor. “That’s just one example of how he took his commitment to commerce and to the community seriously. He lived in the community and worked for and on behalf of the community.”

As chair of the Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce, Wiley pushed it to be more aggressive in improving diversity in the city’s business community. As a result, the chamber launched a serious initiative to make the city’s business community more welcoming to people of color.

Whether addressing young award recipients about the importance of cultural diversity or moderating a dialogue at a local high school about African Americans and the Civil Rights Movement, Wiley gave of his time to young people.

“Flash was jovial, personable and was a guy who had so much fun in life,” said Taylor. “There were very few people who could talk about your Mama, and you would laugh with him. That should give you an idea of how he connected with people. Flash always had a smile. He was never down, never upset about things. Even as his health declined, he never complained. When you went to see him, he would talk to you like you were the patient.”

With no intention of slowing down, Wiley at 78 said, “I’ve been banging on doors ever since I got to town. Not a day goes by when I don’t do something that tries to advance the positions, either politically or businesswise, of African Americans in the city of Boston.”

He was also concerned about Black people’s access to the ballot. In March 2021, in the wake of Georgia and other states making it harder for Blacks to vote, Wiley and his wife Benaree were among the more than 70 business leaders from across the country who signed a letter demanding that corporate America denounce legislative efforts by states to pass more restrictive voting laws.

“It is important at this hour to not just praise him but emulate him, particularly the next generation coming up,” said Taylor. “I find that most of them are trying to be focused on being downtown and not spending as much time as they could uptown in Roxbury, Dorchester and Mattapan. Flash’s life legacy is his activity, both uptown and downtown, and my hope is that many will follow that legacy.”

Wiley is survived by his wife, longtime business leader Benaree Wiley, brother Keith Wiley, sister-in-law Sharon Pratt Kelly; and his son Pratt and his partner Jesse, as well his daughter B.J. and her husband Les.