‘Ernest Cole: Lost and Found’ — Poignant documentary explores life and work of exiled South African apartheid photographer

Banner Arts & Culture Sponsored by Cruz Companies

Apartheid was legal systemic racial segregation in South Africa from 1948 to 1994. Apartheid spanned legal and economic segregation and social separation between European South Africans and non-white South Africans, favoring the former and discriminating against the latter.

“House of Bondage,” which was first published in New York, was banned in South Africa for depicting these harsh realities to outsiders. The country was already impacted by UN-sanctioned boycotts a few years prior. This book ban subsequently forced Cole into exile in Europe and America for the remainder of his life. His exile became a bondage of its own and he often wrote, “I am homesick, and I cannot return.” Originally lauded by his contemporaries for his work covering apartheid, Cole eventually became homeless, faded into obscurity and died from pancreatic cancer at 49.

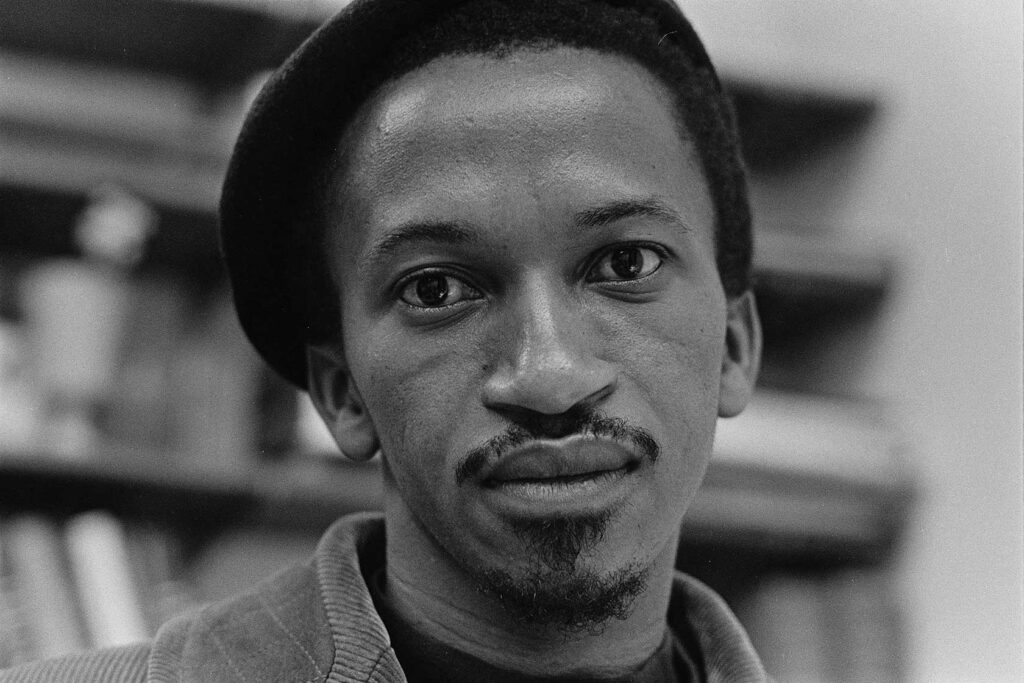

Haitian director Raoul Peck’s (“I Am Not Your Negro”) latest documentary, “Ernest Cole: Lost and Found” spotlights the South African photographer using his photographs and his words with an emotional and visceral voiceover by Lakeith Stanfield (“Get Out” and “Atlanta”). The short and slender observer who stood at 5’4” was marked by feelings of otherness and restlessness throughout his life. The moving and poignant film reveals what happened to Cole between the release of his photobook and the shocking discovery of his lost negatives and writings in a Swedish bank 50 years later. What follows is the story of a man who falls into depression caused by the isolation of exile and the hopelessness that occurs when the Western world promises freedom and fails.

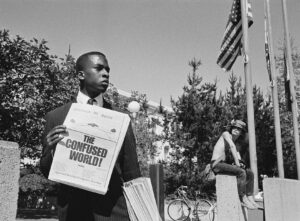

Ernest Cole photograph from the film “Ernest Cole: Lost and Found.” PHOTO: © ERNEST COLE, COURTESY OF MAGNOLIA PICTURES

Cole’s mostly black-and-white film photographs cover an array of daily life, from the dignified and the destitute to the happy and the hopeless. Pictures of “nightmare rides” show train cars and platforms designated for Black South Africans that are packed to the brim. Some commuters grasp onto any bit of the train they can find as they hang off the speeding locomotive, praying they don’t fall to their deaths. He also photographs a white South African sitting on a bench labeled “Europeans Only” and captures the monotonous life of Black South Africans in the desolate, eerily quiet banishment camp of Frenchdale, near the Botswana border.

Cole’s work was inspired by French humanist photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson’s “The People of Moscow.” These were photographs of ordinary people doing ordinary things in ordinary environments. Cole explains that this approach was the most effective way to depict the realities of injustice and human rights violations in South Africa.

It is at times difficult to decipher where Cole’s photographs are set. Is the image of a Black man being brutalized by both Black and white police happening in Chicago or Soweto? Is the image of a Black female nanny to wealthy white children who will learn to hate her set in Pretoria or on Park Avenue? The images taken in the 1960s and 1970s could also be taken today. This lack of distinction is the point.

Ernest Cole photograph from the film “Ernest Cole: Lost and Found.” PHOTO: © ERNEST COLE, COURTESY OF MAGNOLIA PICTURES

Chillingly, Cole also reveals, “In the South I was more scared there than I ever was in South Africa. In South Africa I was afraid of being arrested. In the South when I was taking pictures, I was terribly frightened of being shot.”

Two years after apartheid’s end, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was formed. Established in 1996 and chaired by South African Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the commission allowed survivors of human rights abuses under apartheid to share their experiences publicly. These abuses included simulated drownings, electric shocks, sexual abuse, kidnapping and violence. It also allowed violent perpetrators to give accounts of their actions and request amnesty. The idea for the commission was for people to acknowledge the truth while moving forward with repair and restoration. The reconciliation was televised.

Peck explains his choice to include this archival footage when he says, “I knew that at some point, I needed to show the naked truth: barbarity, abuse, torture.” He continues, “People forget it. They think apartheid is just a figure of speech. No, people were dying. People lived their whole life under constraints, like prisoners of their own country.”

While Cole’s people were prisoners in their own country, he always felt like a prisoner outside of his. His homecoming was bittersweet since he returned posthumously. He died a week after Nelson Mandela’s release from prison.

“Ernest Cole: Lost and Found” is now streaming on most platforms.