Peace family. I think it’s important to start with that as I want us to find and live in our own versions of peace. There seems to be landmines and dumpsters at every theoretical corner that we walk or drive past. I wanted to speak on the recent call for boycotting of Target and BJ’s Wholesale Club as they have publicly rolled back on diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives that they have pledged back in 2020.

It seems that with the recent administration’s focus on eliminating those initiatives, there are a plethora of corporations that are falling in line and, although to some it’s not surprising, it is certainly causing mixed conversations in our community.

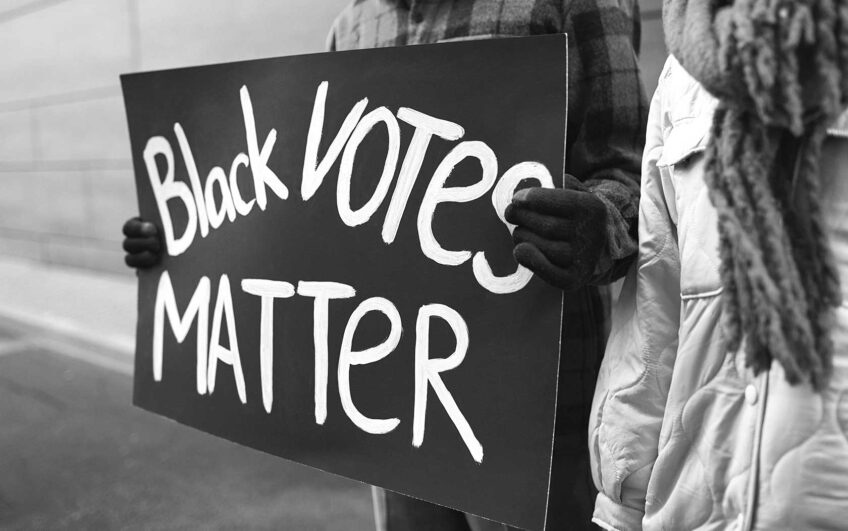

Throughout history, Black communities have used economic boycotts as a powerful tool for resistance, empowerment and social change. Boycotts have served as a means to protest racial injustice, economic exploitation and discriminatory laws, forcing businesses and institutions to acknowledge the value of Black consumers and workers.

From the early 20th century to the present day, Black boycotts have played a crucial role in shaping civil rights movements and fostering economic self-determination. One of the earliest recorded Black boycotts took place in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Following the end of Reconstruction, Black Americans faced segregation, disenfranchisement and racially motivated violence. In response, they began to organize economic boycotts to resist racial oppression and foster self-sufficiency.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott: intention vs. impact

A notable example was the 1905 boycott of segregated streetcars in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Black residents, frustrated by the city’s refusal to provide fair and equal transportation, organized alternative ride-sharing systems. Similar boycotts occurred in other cities, demonstrating the economic power of Black communities when they mobilized collectively.

Perhaps the most famous Black boycott in American history is the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-1956. Sparked by Rosa Parks’ arrest for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white passenger, the boycott was a coordinated effort led by the Black community in Montgomery, Alabama. Under the leadership of civil rights activists, most notably Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Black residents refused to ride the city’s segregated buses for over a year, crippling the transportation system and forcing a national conversation on racial injustice. It has been estimated that the boycott cost the city of Montgomery $3000 a day.

Modern day: Black dollar

In the 21st century, Black boycotts continue to be a powerful force for change. Movements like #BoycottBlackFriday and #BankBlack encouraged Black consumers to redirect their spending toward Black-owned businesses as a means of economic empowerment. The 2020 #BlackOutDay movement, which urged Black Americans to only support Black-owned businesses for a day, highlighted the significant financial impact of the Black dollar.

The rise of social media has amplified the reach and effectiveness of modern Black boycotts. Hashtags and viral campaigns quickly mobilize support, forcing corporations to address issues of racial discrimination, unfair labor practices and lack of diversity. Companies that have been called out for racist policies or lack of representation have faced financial repercussions, proving that economic resistance remains a relevant and effective tool for advocacy.

I think it is important to give context to the history and importance of us as a community collectively using our dollar as power in a world of corruption with lack of transparency and symbolic tokenism. We are today faced with a call to collectively boycott Target who made a public statement opposing inclusion, equity and diversity. The call is not to go inside those doors and only support Black businesses. Boycotts do not work that way. There is no going into work and clocking in and just refusing to answer the phone as a protest. Just by showing up, you are crossing the line in the sand. The businesses that are there have other direct means to support them, which is essential as we always want to flex powernomics. Thank you, Dr. Claude Anderson.

Please take this seriously and understand the assignment and be on code. This is bigger than Target and there are others currently and to come, but the point is we must understand our roles and be on code.

You may not be an activist; you may not be someone that will march. Maybe you call legislators, maybe you sign petitions, maybe you donate to organizations who are doing that work or simply redirect your dollars. This is not an opportunity to be an outlier and think differently.

Freedom of thought and not following the crowd and being a sheep is what my daddy taught me from the age of 4; however, this is not a moment of creative actions within the boycott. For example, maybe you go in and only buy this or maybe you go on the website and buy that. This is an in or out moment. Whatever your position is, stand on it, but also understand what you are effectively and ultimately saying at the same time.

Take this opportunity to seek out Black businesses that have been anxiously waiting to welcome your business. With these sentiments, as the founder of Black Dollar and cofounder of For Your Review Services, I am never encouraging mediocrity with your purchases and settling for less. So, while I encourage you as a consumer to put a 10x supercharge on every dollar you possess, I ask the business owners to show up, show out and prove why you deserve to get that reallocated dollar.

With love,

Daniel Laurent.

Daniel Laurent is an executive film producer of the award-winning short film “Cry for me,” which is about domestic violence and sexual abuse. He is also the founder of Black Dollar, an intentional messaging opportunity that provides the community with a way to be on one accord and on code.