Partnership between Metro Boston Alive and Mass General Brigham fosters new trust for addiction care

When Metro Boston Alive, a recovery center near Nubian Square, joined Mass General Brigham to work in nearby communities to address challenges around substance use disorder, it was an unlikely partnership.

Greg Davis, who runs Metro Boston Alive, said he has generally respected Mass General Brigham’s medical professionalism but didn’t have high hopes for their engagement with Boston’s communities of color.

Over the past about three years, however, since his organization joined MGB’s Bridge Clinic, which offers immediate and low-threshold access to substance use disorder treatment, Davis has come to work closely with and started to rely on staff from the New England hospital system — after they all had a chance to balance their philosophies.

“Once we agreed on that, we’ve been able to really do a lot of work,” Davis said.

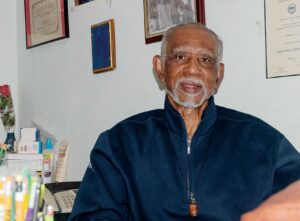

Greg Davis, executive director at Metro Boston Alive, poses for a photo in his office, Jan. 31. Since 2022, the Roxbury recovery program has partnered with Mass General Brigham’s Bridge Clinic to provide substance use disorder support in the community, a partnership that they said has brought new trust to the programming. PHOTO: AVERY BLEICHFELD/BAY STATE BANNER

He said Jasmine Irvin, senior program manager for substance use disorder health equity at Mass General Brigham, is now a partner in the work. She described herself as his “right-hand man.” Much of the success in the program, and something that she said has helped build that bridge, has been allowing community needs to drive the process.

“This has all been community-based work,” Irvin said. “Going into the community, listening, assessing the needs, and then working with community partners in a way that feels helpful to them so that we can work together for better outcomes.”

Through that partnership, which was launched in December 2022, the two groups have hired new staff and launched fresh efforts.

What had previously been an organization run and operated sometimes exclusively by Davis on his own, now has a staff that includes two new outreach workers and a community health navigator.

The program has launched new community meetings at Metro Boston Alive’s headquarters on Malcolm X Boulevard, including running overdose training, and it started to put together resource packages that Davis called “dignity bags” — stocked with hygiene products and COVID-19 tests as well as test strips to see if drugs contain fentanyl and Narcan to reverse opioid overdoses.

A community survey with over 100 responses pushed the partnership to expand its focus to specifically aim services at women and addiction to other substances beyond opioids — areas that Irvin said the outreach forms suggested were lacking.

Davis said that through his work with the community he has seen addiction to a range of drugs.

“We can’t forget about them either,” he said. “We want to include everybody, whatever that means.”

Much of that work has been made possible through trust fostered by bringing in Davis, who has been working on the issue for almost 40 years. That community connection has been an anchor to build trust for residents who might otherwise be hesitant to seek services from an institution like Mass General Brigham.

“So many people are afraid to step into a hospital,” Irvin said. “There has been so much health care and systematic racism in this country for years, especially around substance use disorder, right? So, people can be nervous to talk about care, or to want to reach out and get treatment.”

In the same vein, the partnership has worked on bringing care options to Boston’s communities of color, bringing the Bridge Clinic’s mobile clinic into Roxbury, an effort that has seen some success. Between October 2023 and May 2024, the van treated 33 individuals in 56 visits. Almost all those patients identified as Black.

Of those patients, 75% with alcohol use disorder and 40% with opioid use disorder were placed on medications to support them.

And the mobile outreach is continuing. Clinicians of color are running six addiction sessions in the van monthly in Roxbury and Dorchester, according to Mass General Brigham.

The kind of community connection the partnership aims to foster was also what made him feel he could trust what MGB’s Bridge Clinic was offering, Davis said. Three staff members from the Bridge Clinic had previously partnered with Mass General Brigham.

When he found out where they worked, he was surprised but said it helped him decide to work with the Bridge Program.

Bringing the two groups together still required feeling out where Davis had boundaries and helping him understand what the Bridge Clinic was looking to accomplish and what they do. He said he supports harm reduction measures like naloxone and test strips but is not comfortable providing things like needle exchange or medications like methadone or Suboxone, which are used to treat opioid use disorder. He also said he has no issue referring individuals to facilities that do, if that’s what they want.

Davis said that, previously, he viewed Mass General Brigham’s substance use disorder efforts as not accessible to Boston’s communities of color.

“For me, it was kind of generic,” he said. “I think it was only geared towards folks who don’t look like me.”

But now, he said, programs have helped address some of that image.

And through that work, there’s been a shift, with more community members looking for and being willing to access services.

Irvin said she’s presented about resources that MGB offers, feeling like her words don’t have an impact, only for someone to reach out in response.

“You think it falls upon deaf ears, and then someone calls you and says, ‘Hey, I know you were talking about that Bridge Clinic,’ or ‘I know you were talking about care; can you kind of direct me to what that looks like?’”

The kind of trust that fosters, she said, will make people more willing to go into those spaces and feel more comfortable.

“Us continuing to show up, and for people to know that we’re actually here and that we have people of color on our team that are from the communities, that’s going to build the trust up where somebody will say, ‘You know what, let me try this,’” Davis said.

And it has also meant that, as a large hospital system, MGB has had to reconsider how it approaches connecting residents to services.

“I think it’s been really great for Mass General Brigham to think about health equity and how we can really step out of walls and go to the people who need it most, as opposed to people coming to us,” Irvin said.

For his part, Davis has been glad to see the shift and the growth in trust but thinks the hospital system can do more. He said he’d like to see more funding come to initiatives like their partnership.

“I think we’ve become an example for Mass General to take a closer look at: what more they could do in the communities of color,” Davis said. “It’s still my hope that they will.”

As a bigger dream, he said he thinks Mass General Brigham should open a Bridge Clinic location in Roxbury, so community members don’t face another barrier by having to go downtown to access care.

“If we had a bridge center or a health center right here, it would benefit and make Mass General look a lot better and the valuable services that they have, folks could access it,” Davis said.

If a center like that were to exist, he said, it would have to be staffed, at least in part, by people who Roxbury residents trust.

As the partnership continues, much of the work will be continuing to support the systems they’ve already created, as well as promoting the connection through measures like working to give direct referrals from Metro Boston Alive to the Bridge Clinic.

However, some recent grant funding is looking to push the extent of the work. Through a grant from the city, the partnership is preparing to extend its reach off the streets and into other parts of the community facing challenges around substance use disorder. Metro Boston Alive is seeking a city grant to do outreach in housing run by the Boston Housing Authority, an effort to address what Davis called the “hidden epidemic in public housing.”

That effort will start by targeting efforts at the Mildred C. Haley Apartments, South Street development, and Franklin Field Apartments and will include education and outreach as well as providing resources like naloxone.

“A lot of the times when we do outreach work, we’re meeting people on the street or people who are homeless, but we’re really missing an untapped community,” Davis said. “Not everybody who has substance use disorder is homeless.”

And, with the support of MGB, Davis is looking to get Metro Boston Alive established as a community naloxone program with the city. The Boston Public Health Commission has, in recent years, made increasing access to the drug, which can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, a priority, including through novel solutions like free kiosks and vending machines.

Further down the line, Davis said he’s hoping to be able to expand how many outreach workers he can send out into communities across Boston — his vision, he said, would be 10 to 15 in total — with about three outreach workers dedicated to specific areas around the city.

The partnership started when the team at Mass General Brigham reached out to Davis, who said he doesn’t know why they chose him, but he’s glad that they did.

Irvin said that choice came from his long-term commitment to the community, even when he was tackling the work largely as a one-man show.

“We wanted to work with and learn from people who had been doing this work and pouring into the Black recovery community before anyone else cared about them,” Irvin said. “He’s been doing the work before it was trendy.”