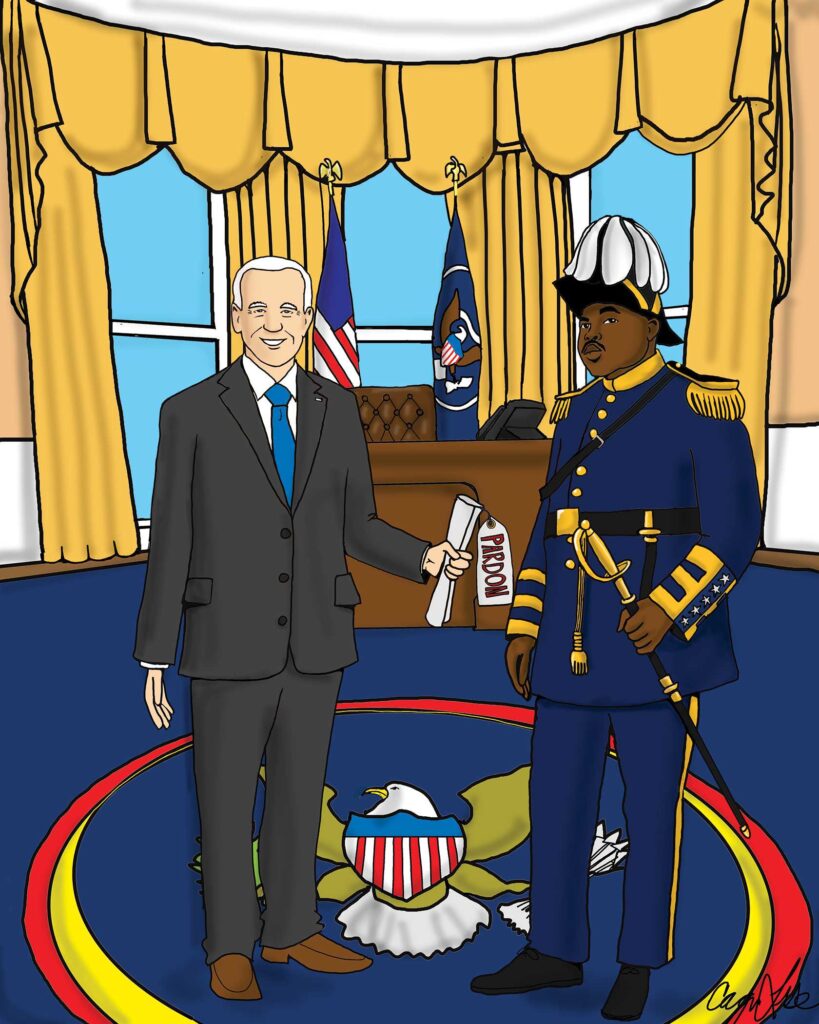

Better late than never. The old saying, a favorite of parents, certainly applies to Joe Biden’s pardon of Marcus Garvey on the 46th president’s last full day in office. Garvey built a mass movement, stretching from the United States throughout the African diaspora, until a federal court convicted him of mail fraud in 1923 — a case Biden noted was fraught with racial and political bias.

Biden was not the first president to recognize injustice in the targeted prosecution and apply the power of executive clemency. In 1927, Calvin Coolidge commuted Garvey’s five-year sentence after he spent two years in prison, on the condition he be deported to his native Jamaica.

Successive governments of Jamaica had called for Garvey to be pardoned for 40 years, making the first appeal to Ronald Reagan and the last to Biden. Members of the Congressional Black Caucus, Garvey’s descendants, Jamaican immigrants and Black activists joined the call for a posthumous pardon.

Garvey has been officially declared a national hero in Jamaica, where his portrait graces the country’s 100-dollar bill. The pardon dominated the front page of the two daily newspapers in the island nation the day after the announcement. “46 is the Lucky Number,” read the headline of the tabloid Observer. “US 46th President Biden does what predecessors shied away from and pardons Marcus Garvey,” was the other headline. The Gleaner led a package of three stories with calls to go beyond pardoning him and to exonerate him of committing a crime. Given the separation of powers, no president or Congress could do that, and a federal court rehearing a case more than 100 years old is most improbable.

The pardon raises the question of Garvey’s relevance more than a century after he launched his movement and was convicted to stop it, and to discredit him. The ripple effects of his impact are still felt today around the world, including in Boston.

Scholars credit Garvey with conceiving an enduring strand of Black thought: Black nationalism. He founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in Jamaica in 1914 and, two years later, moved its operations to Harlem, where the fledgling organization attracted flocks of followers. His movement was loosely labelled a “Back to Africa” movement. He preached what can be called a “do for self” strategy: Black people should run their own country in Africa and manage their own affairs and uplift — a radical thought at a time as most African Americans lived under Jim Crow, and Caribbeans and nearly all Africans lived under the yoke of European colonialism.

Garvey founded the Black Star Line to ship people and goods to Africa, which Biden noted was the first intercontinental transportation company under Black ownership. He also established a corps of Black Cross nurses and a newspaper, The Negro World.

Garvey gave public speeches in Boston at least four times. The first came in 1916, on a national tour to promote the UNIA. He spoke here three times in 1924 at a Congregational church and Masonic Hall in the South End, while appealing his conviction, and before a “large colored audience” in Jordan Hall at the New England Conservatory of Music, according to the Boston Globe.

Remnants of his UNIA still exist here and there. His Black nationalism influenced other organizations and individuals who carry on to this day. Elijah Muhammad, longtime leader of the Nation of Islam, adopted Garvey’s “do for self” approach and desire for a Black nation. Garvey’s derivative impact can be found in Grove Hall at the Muhammad’s Mosque No. 11, long led by the late Minister Don Muhammad. Minister Don orchestrated the development of the Mecca shopping center and collaborated with Boston Police to chase crack cocaine dealers out of Grove Hall.

Nearby is the Imani House, the organizational home of Sadiki Kambon, a self-declared Black nationalist. He directed the Black Community Information Center’s efforts to protect Black children during the violent backlash to school desegregation in the 1970s. More recently, Kambon was a prime mover behind rebranding Dudley Square as Nubian Square.

The impact of two direct disciples of Garvey endures in Boston though both have passed. Ruth Batson and Elma Lewis were children of Garveyites.

Batson raised the alarm that led to a lawsuit desegregating Boston’s public schools. In a videotaped interview for “Eyes on the Prize,” a public television series on the Civil Rights Movement, Batson noted that her parents were from Jamaica and her mother was a Garveyite and Black Cross nurse.

“Every week, every Sunday, there were meetings held in a hall that was called Toussaint L’Ouverture Hall,” Batson said. “And I would have to go with her to these meetings. And at these meetings, I heard ‘Africa for the Africans at home and abroad,’ and we heard racial issues constantly being discussed. And so, as I grew up, I was not swayed as much as some people I knew by this business of Boston being such a wonderful place to grow up [in], being such a great city, with the cradle of liberty. I knew … there were flaws in the cradle of liberty.”

Toussaint L’Ouverture Hall, named after a hero of Haiti’s revolutionary war, was in Lower Roxbury on Tremont Street, a few doors from St. Cyprian’s Episcopal Church.

School desegregation opened new educational opportunities to Black students and exposed the contradiction between Boston’s image and institutional racism, a fissure the city is still trying to close.

Elma Lewis, best known for her school of performing arts in Roxbury, was the daughter of parents from Barbados. Both were Garveyites. The National Center of Afro-American Artists, which she also founded and still exists in Roxbury, describes her this way: “Miss Lewis possessed an extraordinary will inspired by Marcus Garvey’s philosophy of self-reliance and nationalism. She visualized an artistic and cultural center that would empower and dignify Black creative and intellectual development and celebrate Black artistic genius on the world stage.”

Over the decades, her school shaped thousands of Black students from Boston who are still alive and making positive contributions, and not just in the arts. Another enduring legacy of hers is Edmund Barry Gaither, whom she recruited to run the National Center. He remains a wise asset to the Black community.

In his day, Garvey faced criticism from other African American leaders. He and W. E. B. Du Bois of the NAACP, for instance, did not get along at all. Part of the tension sprung from a perceived conflict between his Black nationalism and the NAACP’s integrationist approach. That need not be as Garveyites Batson and Lewis demonstrated.

Batson worked through and with the NAACP to file the desegregation lawsuit. Lewis extracted resources from white institutions to build Black arts institutions. Garvey’s pardon, his life, and his enduring influence reminds all Black people that there’s no conflict between doing for ourselves and working with each other to uplift Black people. And in the world today, we need to work together more than ever to achieve our goals.

Ronald Mitchell

Editor and publisher, Bay State Banner