A familiar face has retaken the White House, promising to pursue America’s “manifest destiny” and restore the country back to its former glory.

For some, that evokes a feeling of patriotism and nostalgia for the days of American exceptionalism. For those who have been the exception to those ideals, it is repudiating.

This message arriving on MLK Day added an undeniable layer of irony, given that President Trump’s return to the White House marks the end of an era when chances for electing a Black and South Asian woman to the nation’s highest office were the highest they’ve ever been.

While the opening days of the second Trump administration are undeniably a spectacle, I find myself still thinking about the time I spilled some tea with then-Vice President Kamala Harris about a year and a half ago. My GBH News colleague Jim Braude and I interviewed Harris for the 114th annual NAACP Convention in Boston. As I told her, I wanted to go ahead and set the tone.

“We all have at least one thing in common,” I said. “And that is love for Tupac Shakur.” Harris is from the Bay Area, Jim was once his babysitter, and I am a lover of hip-hop.

“That is amazing!” The soon-to-be lame duck VP replied with her signature laugh, silk press framing her face.

At that moment, I felt a pang of patriotism I hadn’t experienced before.

Growing up, there were a number of times I felt proud to be an American. I remember flaunting my red, white and blue at the July 4th cookouts where my big, multigenerational family set up picnic tables in my great-uncle’s backyard. My eyes widened at mail I received from the White House in response to letters my class wrote to the president. I even cried when an independent gubernatorial candidate upset the fictional Federalist and Nationalist parties during my week at Girls State, a nationwide summer camp that brings high school girls together to model democracy from the ground up.

Then there was the morning after Barack Obama was elected president in 2008. I was in ninth grade, elated as I bounded into my geometry class. Just before our lesson began, a blonde girl whom I once considered a friend said bluntly, “A Black man can’t be president.”

For her, those two images — a Black man and the Oval Office — couldn’t be more at odds. For me, her suggestion hinted that American pride may not be for me after all.

Throughout American history, images of Black women have been symbolized as the mammy, the welfare queen, the Jezebel, the Sapphire — and yes, the tragic mulatto. Meanwhile, the women themselves have surpassed and outsmarted their literal and figurative captors.

There are also the Black women who became symbols of our democracy by paving the way for Kamala Harris with their own firsts: Congresswomen Shirley Chisholm and Maxine Waters, Senator Carol Moesely Braun, former Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice, and Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson. They’ve all embodied patriotism in their own unique way, whether it was Chisholm throwing up a peace sign, Waters reclaiming her time, or Condi taking a no-nonsense approach as if she were pulling from a football playbook.

So, what do we do with the image of a Black and Asian woman who made it all the way to the top, but fell short?

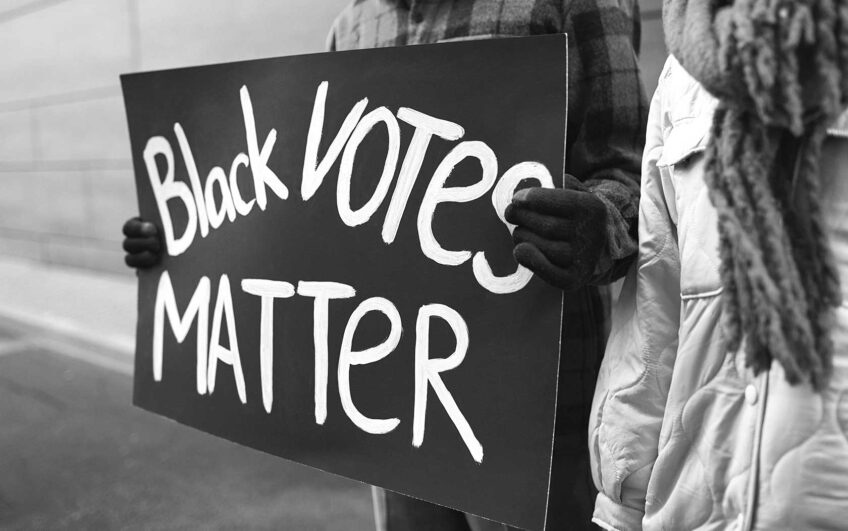

We’ve heard over and over how Black women are the backbone of the Democratic Party. Harris herself won 90% of their votes in 2024, continuing a decades-old trend. But it was more than just identity politics; a recent study from Boston University’s Department of Political Science shows that civic duty is the very thing that gets this voting bloc to the polls. That is a symbol of patriotism in and of itself.

A few months ago, I was driving along the backroads of the rural North Carolina town where I partially grew up. While we lived in the racially mixed city of Greensboro, I attended high school about 20 miles away in a small, rural and predominantly white community where my father was a teacher.

As I drove, I listened to Beyonce’s “Cowboy Carter” — the perfect backdrop to the sheep, horses and cattle grazing on the lush, green countryside I marveled at every morning growing up. I saw several Trump signs along the route — some small and posted in the grass, others waving in the wind with the cadence of an American flag.

For many Black Americans, the stars and stripes have always carried a dual meaning. They are recognizable as symbols of unity, but fade with the lingering question, for whom? It makes me think of the black and white version that the hip-hop duo Outkast posed in front of for their Stankonia album. Erasing the color from it didn’t mean it wasn’t still there or didn’t wave, but it reminded us that the perilous fight continues.

My high school mascot was a Patriot. I remember questioning, even then, whether I could truly be one because of my existence as a proud descendant of enslaved people. Yet in that Boston interview with Vice President Harris, I was able to relate to one of the country’s highest officials by way of Tupac. Or time-consuming hair appointments and awkward dance moves. Or standing in your Blackness even when people question it.

At the same time, representation could only take our nation so far. For many Americans, there was so much about Harris that did not connect: her bubbly persona, her record on crime, her policy platform, and her stance on the war in Gaza, to name a few.

Even as Harris ceremoniously certified her own election defeat before Congress earlier this month, the pageantry has proved to be a distraction from the fact that the Democratic Party has ignored repeated cries for help from the Americans to whom it has made so many promises. To be honest about these criticisms, while still acknowledging that no candidate is perfect, is patriotic in its own right.

These days, it is easy to surmise that patriotism skews toward people who are white, especially men. But in the year Kamala Harris’ presidential campaign went as far as it could, we saw a Black superstar juxtaposed with the American flag for the cover of her album. Others waved Old Glory as they collected gold medals at the Paris Olympics. And Harris stood before it as she promised to protect our freedoms.

It all made me wonder: Is this what patriotism feels like for people who have symbols they can point to all the time, everywhere they turn?

Perhaps patriotism remains accessible for all who want it, no matter who is in the Oval Office. For now, that person is not a Black woman. But that doesn’t mean she doesn’t still represent America.

Paris Alston is a reporter for GBH News.