Environmental justice is ‘another branch on the civil rights tree’

For advocates, MLK’s work sits at the root of modern environmental justice efforts

In 2024, the evidence and impact of a changing climate were on display.

More extreme storms swept the country and, this month, the World Meteorological Organization confirmed that 2024 clocked in at the hottest year on record, with global temperatures likely reaching more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

As the impacts from climate change grow, the disparate impacts on communities of color and lower income communities — often designated as environmental justice communities — are not lost on the organizers and advocates working in the climate justice space.

For many of those advocates, these present-day fights are intricately tied in with the historical legacies of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders from the 1960s.

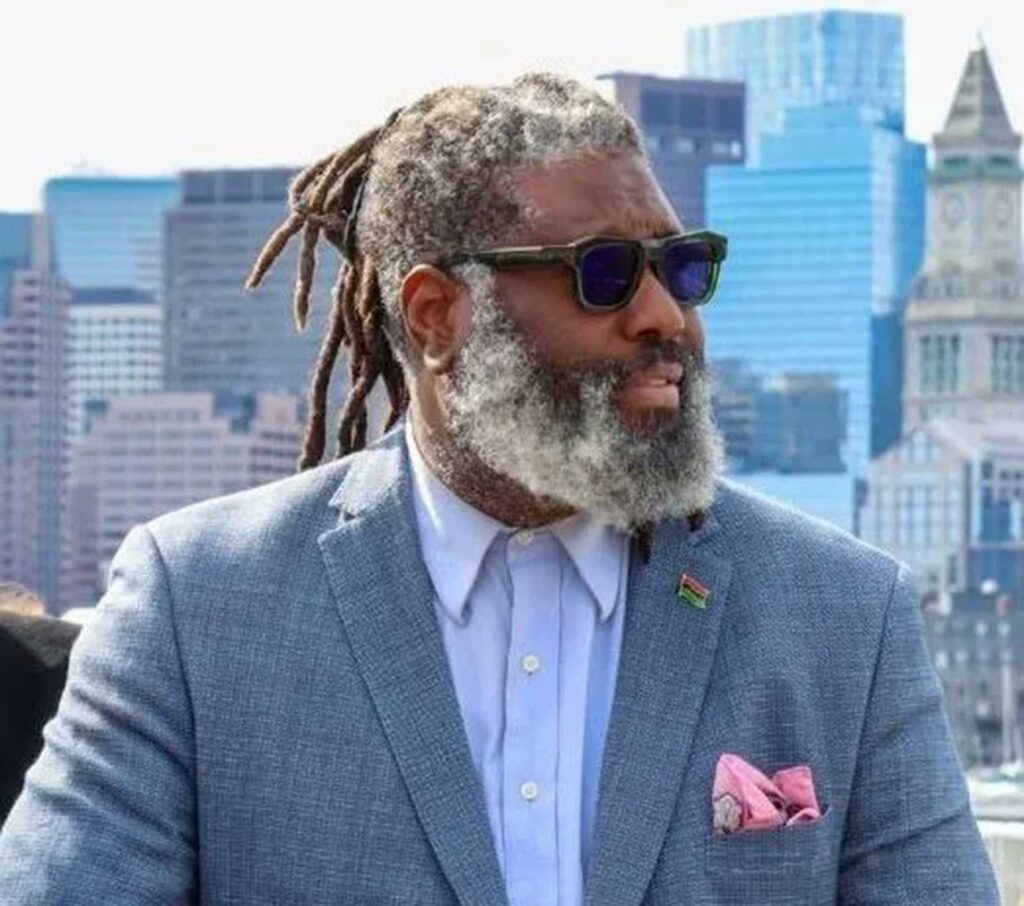

“[Environmental justice] is a civil rights issue,” said Dwaign Tyndal, executive director of Roxbury-based Alternatives for Community and Environment. “Environmental justice is what civil rights looks like relative to our public health.”

King’s work wasn’t largely focused on environmental fights during his lifetime and the term environmental justice wasn’t coined until 1982, almost a decade and a half after his death, but those working on the issue today see it as all part of the same efforts.

“I think, in a lot of ways, you could think about the environmental justice movement as being another branch on the civil rights tree,” said Kalila Barnett, senior climate resilience program officer at the Barr Foundation.

For Brittney Jenkins, vice president of environmental justice at the Conservation Law Foundation, much of the message King shared is present as she and others work to make sure environmental harms and benefits are equitably distributed.

“When we look back on the words that Dr King spoke, and other social justice leaders, they ring very true to the fights that we still have right now in the environmental justice movement,” Jenkins said.

She pointed to King’s 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” in which he wrote, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

“That’s exactly what we try to fight for in the environmental justice movement and to highlight,” Jenkins said. “If one community is being harmed, we’re all being harmed.”

For Tyndal, the movements aren’t just connected, but one and the same, and contemporary fights around environmental justice are a way for new generations to find their way into the broader civil rights movement.

“If they are coming through the door of climate justice, then the room should be called civil rights,” Tyndal said. “Right now, that’s probably one of the most difficult things to educate people [about], that this is your civil rights.”

He said that, to continue the fight for justice, each generation needs to revisit civil rights and what that means — as well as what protections exist to keep public and private entities accountable.

“When people look at climate justice, environmental justice, public health and they disconnect them from civil rights, that’s where the problems start,” Tyndal said.

In no small part, for him, that is because the issues are so intertwined. For example, conversations around housing justice are tied in with concepts of building emissions and air quality — in Massachusetts and Boston, there have been some efforts to bring the two together at a governmental level, with state and local officials advancing efforts around cleaner, greener public and affordable housing — or being able to stay and settle in and build a healthy neighborhood without being displaced.

“Housing, redlining and [environmental justice] public health is so interconnected,” Tyndal said.

“If we don’t deal with the housing issue, most of these issues will be null and void relative to the wellbeing of the Black community.”

Work in that space, especially at the state and local levels, is important in this moment, Jenkins said, as climate and environmental advocates prepare for the incoming administration of President-elect Donald Trump, a shift many expect will bring reduced federal investment in green initiatives.

“In many ways, I think that’s where a lot of the wins have been in the environmental justice movement,” Jenkins said. “It’s been the fight that community groups, advocates, organizers have been able to do on a local level to stop these facilities from being built in their neighborhood, to close a polluting industry, to pass stronger environmental justice laws on the local and state level.”

Part of that work, Barnett said, will be continuing to press federal leadership in departments like the Environmental Protection Agency to continue investment in environmental justice efforts.

“We don’t want to just automatically give up, even though there is some threat,” Barnett said. “I think that’s one of the pieces that’s important. Regardless of who is in the White House, our federal government still has this important commitment to the communities that have been most harmed.”

Part of that is considering new sources of funding to pursue initiatives locally.

Tyndal, whose organization works to address environmental harm in Boston’s communities of color, said he believes that there are private sector partners willing to get onboard with supporting the efforts that, in the past four years, have seen unprecedented federal investment.

For Barnett and the Barr Foundation, which does philanthropic work to support climate-focused issues locally, the change in administration is a moment to reassess how they approach those investments. She said she’s thinking of this moment as one for private funders to consider how they can extend their support.

For the Barr Foundation, she said, some of that work is considering what potential additional resources could be used to support not just the initiatives that organizations are pursuing, but the staff and members of those groups as well.

“I think that those are important considerations, for philanthropic institutions and for other individual donors and supporters to think about,” Barnett said. “You know, ‘Could you step up in a bigger way, given this difficult time?’”

Supporting that work is a part of supporting modern civil rights efforts.

In work surrounding climate equity, environmental justice communities are officially marked by a set of definitions around what portion of a census tract is comprised of residents of color, what portion is below an income threshold and what part primarily speaks a language other than English.

But for Jenkins, more broadly, environmental justice is better described with a vision that rings with some of the same notes of King’s dream for the people of the United States to be judged by the content of their character not the color of their skin.

“What we’re really trying to say is no matter where you’re born, no matter where you grow up, you have just as much chance and opportunity to breath clean air, to have access to clean water coming from your pipes, to be able to walk outside in green spaces,” Jenkins said. “To shorten that a little bit, you have just as much of an opportunity to enjoy the environment, to engage with nature as anyone else, regardless of your race, your income and other social determinants.”