Banner Sports Sponsored by the Patriots Foundation

For years, college sports masqueraded as an amateur venture while raking in billions of dollars in television and marketing revenue. The National Collegiate Athletic Association was one of the chief beneficiaries of the incredible wealth generated by the games it governed. For over a century, young athletes provided a deep talent pool for colleges while being exploited in the process.

The words “college scholarship” were a joke to any clear-thinking person. Large sums of money were being paid to premier athletes under the proverbial table for their services to their colleges. Forget that this was a clear violation of the NCAA amateur rule, which states that a scholarship athlete can only receive a free education and room and board for their services.

To many people, this seemed like a fair deal. Athletes would get a college degree for their efforts on the field of play. But anyone with scant knowledge of the word exploitation knew this was untrue. Thousands of athletes did not belong in college because they could not do the work required, but that didn’t matter. They were commodities to the colleges they represented — no more, no less. And when their eligibility expired, they could easily be replaced.

The athlete was sent into the world with little or no chance of success. The landscape of college sports is littered with stories of broken athletes with broken dreams. While colleges and their star coaches made billions on the backs of young athletes, the athletes paid the ultimate price.

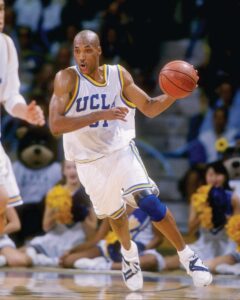

However, this all changed with the famous Ed O’Bannon case in 2009. O’Bannon, the star player on the 1995 UCLA national championship basketball team, took the NCAA to court over his right to profit from his image and likeness. He agreed to be the lead plaintiff after seeing his likeness from the 1995 championship team used in the EA Sports title NCAA Basketball 09 without his permission. The game featured a UCLA player who looked like O’Bannon: He matched his height, shaved head, No. 31 jersey and left-handed shot.

Basketball Hall of Famers Bill Russell and Oscar Robertson both joined the lawsuit. The blog LawInSport analyzed the suit this way: “The plaintiffs allege that the NCAA’s rules and bylaws operate as an unreasonable restraint of trade because they preclude FBS football players and Division I men’s basketball players from receiving any compensation — beyond the value of their athletic scholarships — for the use of their names, images, and likenesses in video games, live game telecasts, re-broadcasts, and archival game footage.”

The case stayed in the news for years and set the stage for where N.I.L. would go. In 2021, the N.I.L. flood gates burst when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a district court ruling that athletes could profit from their name, image and likeness. This idea did not sit well with many people, especially college administrators, who realized their free ride on the gravy train with biscuit wheels was over. The athletes now possess the power to make fortunes off their names, images and likenesses.

Caitlin Clark made millions while playing college basketball at the University of Iowa, becoming the poster girl for N.I.L. wealth. The most recent N.I.L. multimillionaire is Darian Mensah, a quarterback who transferred from Tulane University to Duke University for a price tag of $8 million over the next two years, an N.I.L. record to date. Mensah, a redshirt freshman who worked his way from the scout team to a starting job, maximized his opportunity by throwing for 2,273 yards, 22 touchdowns, and just six interceptions, leading the American Athletic Conference in completion percentage and passing efficiency rating while guiding his Tulane team to the AAC championship game. For that performance, Mensah is going to get paid big dollars.

One recent issue that has started to cause problems in college football centers is the current transfer portal situation. The transfer portal allows student-athletes to place their name in an online database, declaring their desire to transfer to another college without the old rule of sitting out for a year.

Another component of this scenario deals with underclassmen bailing out of college football bowl games to protect their transfer portal and NFL draft status. The latest examples involve players from the University of Georgia, Ohio State University, Arizona State University, and the University of Miami.

In the case of Miami Hurricane All-American quarterback Cam Ward, a surefire first round NFL draft pick, he played just one-half of his team’s bowl game against the Iowa State Cyclones before sitting out the second half of the contest. Miami would lose the game, 42-41, drawing the ire of many Miami alumni and fans.

Ward said that he had only planned to play one-half of the bowl game, which he did. While some may say that this is wrong-thinking, others say that the Hurricanes’ quarterback made a sound business decision to protect himself from possible injury that would have cost him money, which is the main focus of this commentary.

This is all about money and those who control the flow of it. Present-day athletes can control their money stream thanks to N.I.L. and the transfer portal. But where will all this end? And while the powers that run college sports are at their collective wits’ end, the money for college athletes continues to spiral upward.

Critics of N.I.L. and the transfer portal are saying that the current state of affairs will severely damage college sports. My answer is: Where was the concern for athletes over the last 100 plus years when colleges and coaches were making billions? Let’s be clear. Big money is made in college sports. And so much of that money goes to colleges and the NCAA, not the athletes who put on the show for the dough.

For example, the Business of College Sports site points out that ESPN signed a 12-year $5.64 billion contract with the College Football Playoff through 2025, allowing it to broadcast the two semifinal games and the title game. The parties signed an extension through 2031 for an additional $7.8 billion. This figure does not include the money big-time conferences make off the networks before bowl season. Each Big Ten university will make $72 million, as will the SEC and Big 12 conference teams.

It’s now time for the athletes to make their share of the billions of dollars that they generate. This is how things should be in the free-enterprise, capitalistic society in which we live. Today, young athletes are well aware of their worth, a thought that bristles the thinking of some people. The archaic thinking of those people will have to be adjusted to catch up with the times.

A prevailing idea of American thinking is that parents send their offspring to college to make a better life for themselves. But what if the young athlete can make millions of dollars before graduating with a degree instead of incurring massive college loan debt? What sane parent would ever tell their young, gifted athlete not to take that filthy lucre and let it all go to the college as he struggles to get a hamburger, a soft drink, and movie money, while constantly calling home for cash.