Banner Arts & Culture Sponsored by Cruz Companies

A few years ago, archivists around the city undertook a project to digitized the plethora of historical materials in their collections relating to desegregation and busing in Boston. Professionals at Northeastern University, University of Massachusetts Boston, Boston College and Suffolk University along with those at the municipal and national archives scanned boxes and boxes of primary source material, further preserving a tumultuous and significant part of the city’s history.

As the 50th anniversary of the start of busing this year approached, Lew Finfer and his colleagues at the Boston Desegregation and Busing Initiative, which he co-chairs, sought to reflect on the events that took place in the 1960s and 1970s and their impact by hosting forums and events, and relied on the work of the archivists to do so.

“Busing, I would argue, is probably the most important civic event that happened in Boston since World War II, in terms of just the challenges it brought to the city,” Finfer said.

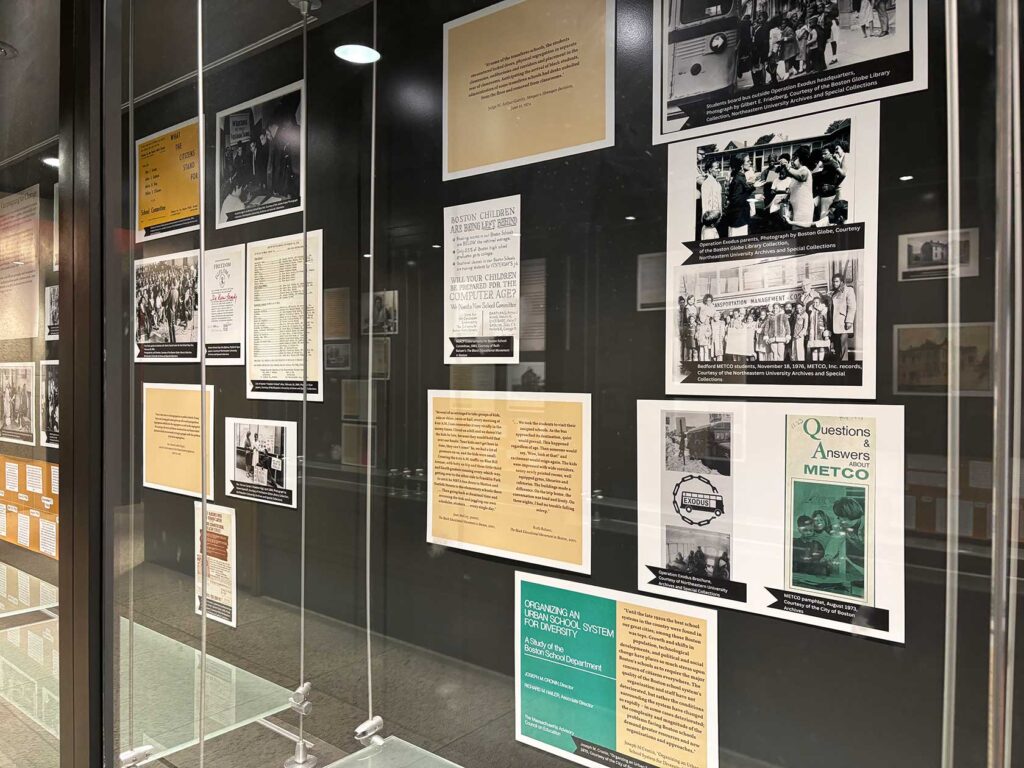

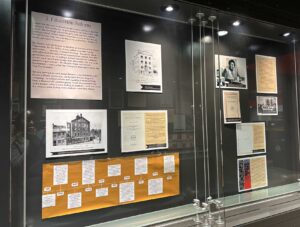

Those challenges are laid bare in an exhibit in Boston Public Library’s Gallery J, located near the door to the library’s entrance on Boylston Street.

Thanks to the work of archivists around the city like Molly Brown, reference and outreach archivist for the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, and historian Jim Vrabel, the exhibit, sponsored by the Boston Desegregation and Busing Initiative, has been on display since September and will be up until Jan. 7, 2025.

“Boston is a city where we encounter history accidentally, no matter where you go, and so I think school desegregation history is not always as public or as visible as it could be,” Brown said. “So, I think just having that be more clear and more visible and more encounterable … just felt really exciting to me.”

In the Boston Public Library’s Gallery J, an exhibit on desegregation and busing tells a brief story of one of the most challenging periods in Boston’s history. PHOTO: Mandible Mpofu

In the past, Gallery J had been used to display reproductions of materials from the library’s special collections, said Katherine Mitchell, the visitor experience coordinator. In the last year or so, the library chose to open the space — a mini hallway comprising display cases — to exhibits by community groups, local organizations and artists, and the desegregation and busing display was one of the firsts.

“We’re a community resource, and we take that really seriously,” Mitchell said. “And so being able to be a space where community members can come and can share their ideas and their work, that is really important.”

The challenge when curating the exhibit was distilling decades of history into a digestible account. Over the course of about a year, Brown and other archivists were tasked with pulling the materials that would form the basis of the exhibit. Vrabel’s challenge was to further streamline the documents and photos to create a concise and cohesive story.

In the end, Vrabel settled on a format that employed a mix of images, written documents and timelines. The story starts in the 17th century with a history of Boston’s relationship with public education and runs through to the 20th century, when Black civil rights leaders and parents organized to desegregate schools and busing began.

“The exhibit acknowledged the violence and the political failures of the time … but it tried to emphasize the history of the demands for improving public education and improving desegregation of Boston schools that have been going on for hundreds of years as a matter of fact,” Vrabel said. “And it tried to emphasize the details of the failings of the school committee and the the awful policy measures that they passed to actively segregate the schools, which people don’t understand.”

Working on the exhibit, Molly Brown tapped into the feelings evoked by the narrative of desegregation and busing.

“When you’re trying to tap into this emotional story, having records to help you understand the stakes of it and also to think about what the work of activism looks like in the real and in the concrete can just be really helpful,” she said. “Now as we think about what education activism can be, I think there is a lot of the past that we can channel and look to.”

Brown pointed to icons like Ellen Jackson who spearheaded the community-led busing initiative Operation Exodus and Muriel and Otto Snowden, founders of the Freedom House in Roxbury.

The exhibit was also a chance to show Boston residents “that archives are for them to participate in and to learn stories from and to contribute stories to,”Brown said.

As the buzz generated by the anniversary of busing dies down, Finfer said he wants people to continue “taking stock of all that was involved” in that period: the major forums organized by community activists in the 1960s, the school committee refusal to acknowledge the inequities in education, and the heroes of the movement like Ruth Batson, who founded METCO.

Vrabel said he hopes the city can learn from the desegregation and busing period.

“The conversation this year has shown how difficult it still is for people to talk about and to get past their emotional response to it and their moral response to it, to maybe focus a little bit more on the public policy implications,” he said. He added that “The other lesson is that the schools can’t solve all the problems that society won’t face and that all parents want the same thing for their children: quality public education, preferably in schools near their homes, and for some reason, we weren’t able to unite people around that understanding.”