2024 year in review: City, state pushed for green transition as climate change concerns loomed

Electric vehicle access, coastal resilience among 2024 initiatives

With rising sea levels and increasing urban heat temperatures, in Boston and Massachusetts, 2024 saw efforts to expand green technology and climate protection, especially with an equity lens in environmental justice communities across the state.

New green technology efforts aim to bring better energy efficiency

Throughout 2024, efforts across the city and state pushed for greater adoption of technology to address the causes and impacts of a changing climate.

In Dorchester, a partnership between the city and National Grid, announced in February, will see a large-scale pilot program geothermal heat pump installed at the Franklin Field Apartments, bringing clean heating and cooling to the public housing complex.

In cold weather, the heat pump, which will replace an aging boiler at the apartment complex, will use underground piping to move relatively warmer air from underground through a system that produces more heat that is pumped through the building.

In summer months, it works in reverse, moving warm air from inside into the ground, cooling the space in the building.

The system comes as part of a broader effort in the Boston Housing Authority to make the city’s public housing stock greener. As part of her State of the City address in 2023, Boston Mayor Michelle Wu announced the city’s goal to make Boston’s public housing fossil-fuel-free by 2030.

Andy Toomajian, business development manager at Revision Energy, shows off the solar array on the roof of the Kenzi an all-electric affordable housing development in Roxbury. The Kenzi is the first building taller than four stories in the city to use technology other than a diesel generator for backup energy needs and came as part of series of efforts to expand an increase access to green technology in 2024. PHOTO: AVERY BLEICHFELD/BAY STATE BANNER

The housing authority has said it wants to prioritize community members who otherwise might be priced out of green-technology improvements.

“It’s really important as we go forward that low-income communities, communities of color, non-English speakers and other populations are not at the back end of the implementing green technologies and planting healthier energy solutions,” said Joel Wool, deputy administrator for sustainability and capital transformation at the BHA in a February interview.

And large-scale heat pumps may become more common across New England. National Grid broke ground on another pilot program in a neighborhood in Lowell in 2023. Eversource started one of its own in Framingham in 2022.

Efforts to bring cleaner energy to lower-income community members aren’t limited to the Franklin Field Apartments. Near Nubian Square, the Kenzi, a new affordable housing development which opened in June, is the first mid-rise building in the state — and perhaps in the country — to be fully electric, even with its back-up power systems.

Generally, all-electric mid-rise and high-rise buildings — those taller than four stories — have a diesel generator to supply back-up power if the electricity goes out. Even when the power is on, that generator has to be tested regularly.

At the Kenzi, however, roof-top solar panels fill two industrial-refrigerator-sized cabinets of batteries that will power elevators, some lighting, fire alarms and the building’s community room in the case of a blackout.

Maria Chavez, an energy analyst with the Union of Concerned Scientists, who wasn’t affiliated with the project, said in a July interview that she sees the Roxbury development as an important step forward for clean energy transitions.

“I feel like it could be a model for future projects and deployments,” she said. “We really need progressive policy that can potentially replicate this model for other and multifamily housing.”

As the technologies expand and become available, community efforts are looking to make sure residents of color are included in the growing workforce.

Sen. Liz Miranda, center, discusses the future of diversity-focused workforce development at the Roxbury Worx conference. PHOTO: AVERY BLEICHFELD/BAY STATE BANNER

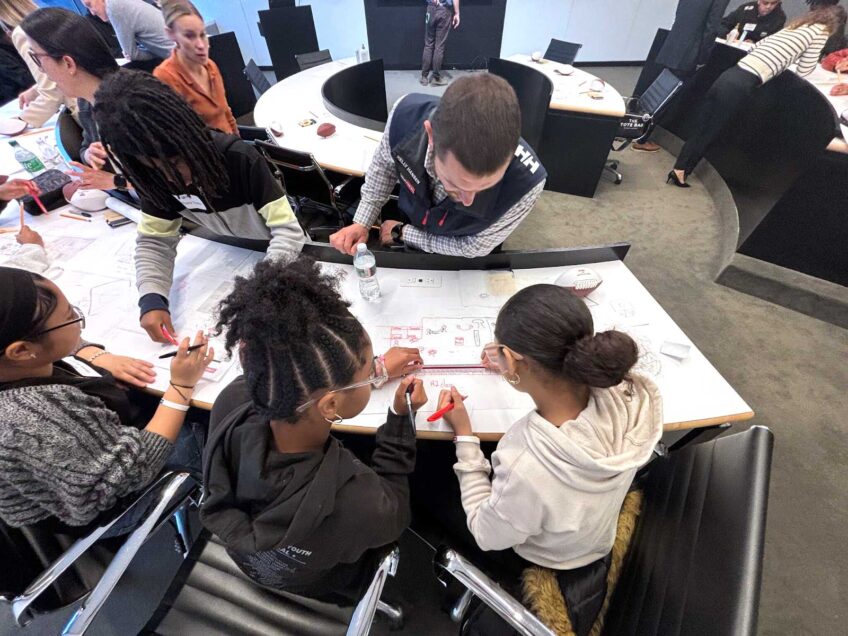

In November, The American City Coalition hosted its Roxbury Worx Conference, an annual gathering bringing together a collection of organizations working to connect community members with jobs in burgeoning science and technology fields, including green technology jobs.

The gathering came amid efforts from other groups to develop a diverse clean technology workforce.

The conference was held at Roxbury Community College, which has made efforts of its own to open jobs in green technology fields to its students.

In November, RCC, alongside the state’s Department of Energy Resources, announced federal investment into the development of an energy auditor training program focused on small- and medium-sized commercial buildings. RCC already has a program focused on energy auditing for residential buildings.

Students in the program will learn to identify how a building’s energy use is working and how it could be improved, the kind of work that will be increasingly important as buildings in Boston stare down next year the first benchmarks under the Building Emissions Reduction and Disclosure Ordinance, city legislation signed in 2021, that requires buildings of a certain size report and reduce their emissions.

The program will start at RCC and at Greenfield Community College in western Massachusetts, with goals to develop a curriculum that can be shared with other schools across the state.

For a developing field that generally has good, stable pay while also taking steps to help address greenhouse gas emissions and climate change, it’s important that the students RCC serves have a chance to be involved.

“It’s an opportunity that doesn’t happen a lot for folks in high poverty areas and students of color to get in on the ground floor,” Pina said.

And over the summer, the Boston professionals’ chapter of the National Society of Black Engineers ran a six-week course for 13 local high school students to expose them to options in so-called “green-collar” jobs. And in May, Governor Maura Healey announced a Climate Careers Fund.

For people of color working in the field, one area for growth would be improved supplier diversity goals, with benchmarks not just focused on diversity generally, but broken down with specifically targeted goals around individual groups like businesses of color, separate from women-owned businesses, separate from veteran-owned businesses.

Overall, it’s a space that has seen progress but still has room to grow, said Kerry Bowie, executive director of Browning the Green Space, a local nonprofit focused on advancing diversity, equity and inclusion in the climate technology sector.

“Generally, I think we’re doing stuff, but I also think there’s a lot more that we can be doing,” said Bowie, in a July interview.

City, state continue to push for electric vehicle access

And electric vehicles continued to be featured prominently among city and state efforts in 2024, with work to increase access to both the vehicles and related infrastructure like chargers.

One major focus is on-street charging options. In July, Wu announced city contracts with vendors to install new EV chargers under two pilot models — under one, the chargers will be owned by the city; under the other, the chargers will be owned and operated by private operators with permission to install them on public rights-of-way. The plan was first announced in July 2023.

A city goal aims to get an electric vehicle charger within a five-minute walk of any resident in the city.

A Sept. 4 meeting of the state’s Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Coordinating Council also tackled the topic, with presentations from three companies on on-street charging infrastructure projects across the state.

Those on-street chargers are considered a key priority, especially in cities like Boston where many residents might not have access to a garage or driveway to charge — a limitation that might prevent them from purchasing an electric vehicle.

“If I can’t charge a car, there’s no use, right? So that’s one major hurdle. Can we do better in terms of providing public charter infrastructure?” said Justin Ren, a professor of operations and technology management at Boston University.

Josh Ryor, assistant secretary of energy in the state’s Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, said that boots-on-the-ground efforts will largely be handled by individual municipalities, but the state is looking to provide financial assistance, including by directing $11.25 million in funding to the quasi-public Massachusetts Clean Energy Center to create a program supporting municipal efforts to expand on-street charging.

Getting the benefits of electric vehicles to the largest number of travelers is also a priority. In October, the city received $4 million in funding to purchase or retrofit school buses serving Boston Public Schools students.

That latter approach — taking existing diesel buses and replacing the engine with battery-electric component — may be able to help make more buses fossil-fuel free sooner, while limiting waste of other components, said Jackie Hayes, BPS deputy director of transportation.

“We want to really look at it from a scale perspective,” she said. “There is a tremendous amount of waste in throwing out the shells of these buses when we could be repurposing them.”

During her campaign, Wu promised to electrify the entire fleet of 750 school buses by 2030.

State efforts are also aiming to connect more drivers — especially those who see more time on the road — to electric vehicles. Under a new rebate program, the state is aiming to make EVs more appealing to taxi and rideshare drivers.

With the rebates, the drivers can get up to a $6,500 rebate from the state for the purchase of a new electric vehicle and up to $2,500 for a used EV.

“What will make this program so effective is that it provides resources to our highest mileage and most public-facing drivers who work hard to help all of us get around safely and conveniently,” said Rep. Jeffrey Roy, who chairs the Massachusetts Joint Committee on Telecommunications, Energy and Utilities, at a Nov. 12 press conference.

Resilience efforts look to tackle coastal resilience, urban heat

But Massachusetts and cities across the state are also working to tackle the impacts that communities are seeing or expect to see soon.

Throughout 2024, Boston and other nearby municipalities continued work on coastal resilience efforts aimed at increasing coastal resilience and protecting the coast from rising sea levels and the worse storms.

In many cases, the name of the game is “green infrastructure,” solutions that look to use nature-based solutions to address climate challenges, rather than building things like sea walls. Those solutions — think restoring coastal wetlands that are naturally better at protecting shorelines or expanding and raising grass-reinforced beach dunes — can be cheaper and more effective.

The view down Island End River, which marks the boundary between Chelsea and Everett. The two cities are working together to build a flood wall and revitalize native salt marsh on the site to close off a flood pathway that could impact infrastructure and residents in coming decades. In 2024, municipalities across the Boston area and the state looked to tackle growing impacts from climate change like coastal flooding and urban heat. PHOTO: AVERY BLEICHFELD/BAY STATE BANNER

“In many instances, nature has been facing these challenges for a long time, and she’s been doing a better job than us,” said Mariama White-Hammond, the city’s then-chief of energy, environment and open space, in a January interview.

That work has also required inter-municipal collaboration. Across the Chelsea and Everett town line, the two cities have joined together to limit the impacts of rising sea levels and storms that threaten to flood through the Island End River, impacting thousands of residents, schools, health centers and a produce distribution hub that serves all of New England and parts of Canada.

That project not only crosses that municipal boundary but is occurring in tandem with eight other efforts along the Mystic River, which feeds the Island End River. Without any one of the projects, flooding may still impact the areas that any one of the projects is trying to protect.

Similarly, broad efforts are targeting urban heat impacts. An effort through the Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization called ““Neutralizing Onerous Heat Effects on Active Transportation” or NO-HEAT, is looking to make walking, biking and public transit users cooler as they attempt to navigate four municipalities in the Greater Boston area.

It’s an effort that leaders see as an opportunity to make it easier to move through the spaces that are most impacted by heat.

“Our least walkable areas are also those that are most prone to heat risk,” said Tom Skwierawski, chief of planning in Revere, one of the municipalities involved.

Though not part of the NO-HEAT project, the city of Boston has taken similar steps, with the installation of 30 green roofs — again, a nature-based solution — one that puts plants on bus shelters along the 28 bus route from Mattapan, through Dorchester, into Roxbury. The new shelter roofs will help cool riders as they wait for the bus.

Ed Gaskin, executive director of the Greater Grove Hall Main Streets organization and an advocate for local green infrastructure, said the shelters are a start, but he’d like to see a broader plan that will tackle environmental needs — especially in communities like his that see disproportionate climate impact — in a cohesive manner.

“Without an overall plan, you just have a bunch of one-off stuff,” he said. “One-off is better than nothing, but at the end of the day, the greening of the bus shelters isn’t going to make that much of a difference.”

Climate leaders brace for a second Trump administration

The tail end of the year was marked by eyes turning to 2025 and the incoming presidential administration of a reelected Donald Trump, and thoughts on how his second term in office will impact conservation and environmental efforts.

In his first term, Trump rolled back nearly 100 federal environmental rules. Throughout his campaigns and time in office, he has waffled on how he describes climate change, sometimes calling it a hoax and other times saying the environment and issues like clean air are important to him.

As he has announced his nominees for various cabinet positions, Trump tapped Lee Zeldin, a former New York representative, as his choice to head the Environmental Protection Agency, a choice that is expected to lead to scaled-back climate change regulations if approved.

To head the Department of Energy, Trump has nominated Chris Wright, who heads the fracking company Liberty Energy.

Trump’s second term comes on the heels of a Biden-Harris administration that issued unprecedented federal investment into climate and conservation in the United States.

“That has made so much of the work possible in infrastructure at the city and state level,” said Hessann Farooqi, executive director at the Boston Climate Action Network, in a November interview.

Expecting the absence of that support, local climate and environmental groups and officials said they are battening down the hatches as they prepare for reduced federal investment.

That’s increasingly important, those leaders said, as Massachusetts and the world see rising temperatures and an increasingly abnormal climate and weather phenomenon. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association found that summer 2024 was the hottest on record in the northern hemisphere.

On Nov. 6, the day following the presidential election, temperatures in Boston neared 80 degrees. Historically, on average, the high temperatures for early November hover in the high 50-degree range

“We have made progress [over the past four years], but in a moment where we really need to really lean in, we’re going to be dialing it back on the federal level,” said Britteny Jenkins, vice president of environmental justice at the Conservation Law Foundation, in November.

But while local climate and conservation leaders weren’t eagerly anticipating the impact Trump’s return to office might have on local efforts, the overwhelming sentiment was that work in Boston and Massachusetts will continue, even without federal support.

In the wake of the election, Brian Swett, Boston’s chief climate officer, said that cities and states leading the charge on climate efforts has largely been the norm — with the past four years as the outlier.

“Elections don’t change the fact that climate change is the existential threat to Boston’s survival for the long term, and we need to address it, and we’re making progress on doing so,” he said.