Banner Business Sponsored by The Boston Foundation

Growing up, instead of reaching for dolls during her playtime, Shamaiah Turner opted for cardboard boxes and Lego. She interpreted this as an indication of an interest in a career in architecture. But a year spent working with Habitat for Humanity where most of the builders were women, an unusual sight in a male-dominated arena, steered her in a different direction.

“That experience gave me the confidence to know that I could do this job, like be a construction worker,” said Turner, business development representative for the Northeast Regional Council of the Sheet Metal, Air, Rail, and Transportation Workers, or SMART, and a member of the organization’s Local 17 union.

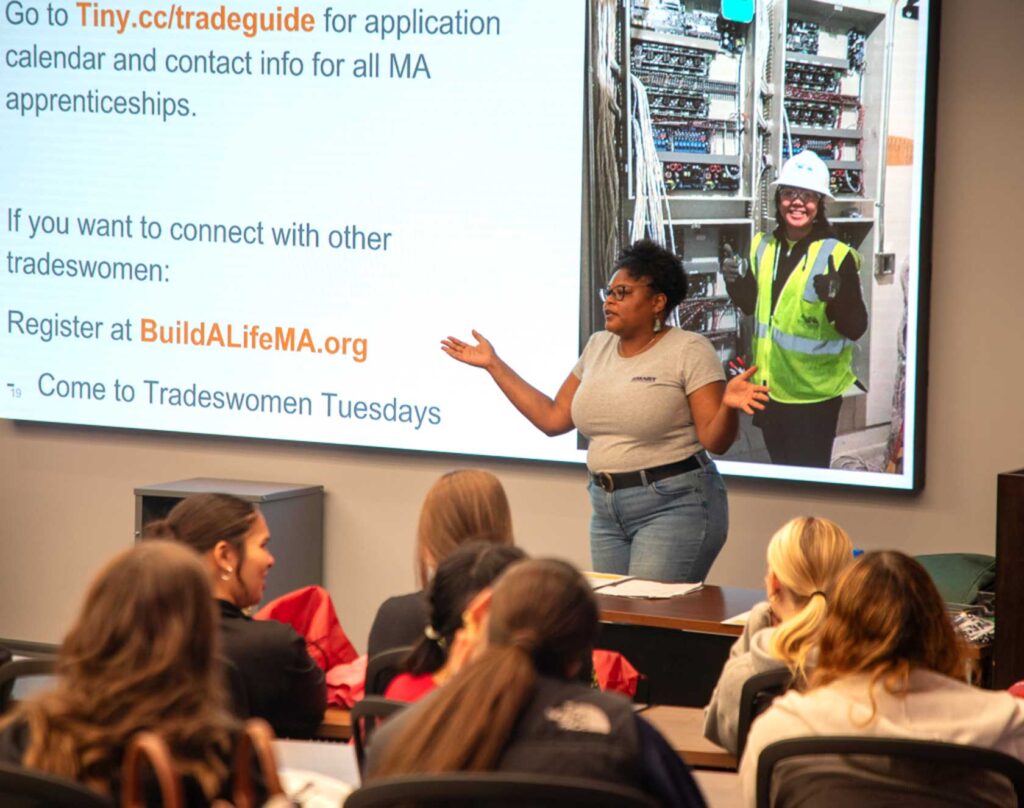

Now, Turner is encouraging other women and girls to consider entering the trades. Late last month, she held a student workshop at the Massachusetts Girls in Trades Conference and Career Fair, an annual convening of women in trade careers and hundreds of young girls interested in similar jobs.

Founded in 2015, Massachusetts Girls in Trades supports middle and high school students in their journeys toward union construction trade careers. The organization’s conference is an opportunity for young girls to learn about career pathways and for organizations like Turner’s to start recruitment early and increase diversity in the industry.

In 2023, women made up just 10.8% of the total labor force of construction workers, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This percentage has remained virtually the same since 2002, the earliest year with comparable data, when women represented 9.3% of the industry.

When Turner began her career as a sheet metal worker 12 years ago, there were just five women in her union, and camaraderie wasn’t exactly the norm.

“There was a culture where … if you did happen to be with another woman on the job, you wouldn’t really speak to her because you didn’t know that woman, you didn’t know if she would make you look bad,” she said. “There was heavy fear of being lumped in together … you didn’t want her mistakes to reflect on [you].”

While progress has lagged over the last two decades, Turner has witnessed some changes in her union, which today has 60 women members, a notable advancement. Communities that support women in the trades, like the Boston Union Trade Sisters, have also sprouted in recent years.

This progress is beneficial for the industry as a whole, Turner said, because women often possess unique skills like strong attention to detail and communication, which are especially important on job sites where multiple trades are working simultaneously.

“We need a capable workforce, and we need a diverse workforce,” Turner said. “And so when we put an investment in that, we can start to see a return.”

Working in the trades also offers women financial independence. Local 17 union members are paid equitably and receive good health care benefits, and Turner also has two pensions and an annuity. Even without having graduated from college, she can afford to own a house in a city as expensive as Boston.

“Women and girls are very capable of doing these jobs. They should know that this is an opportunity available to them,” Turner said. “Also, especially with union construction, we start to close the gender pay gap.”

Suzy Depina-Correia had been working in the human services industry for a decade before pivoting to the trades. In her old job, she worked 60-hour weeks just to make ends meet, and the load began to take a toll on her.

When her cousin, a sheet metal worker for Local 17, the same union Turner is a part of, introduced Depina-Correia to the idea of working in electrical, touting the high pay and benefits, she decided to take the plunge, and she quickly learned that she was just as competent as the men.

She recalled hauling two 25-pound boxes at a time up and down extension ladders and operating pulleys during her first job. While some people may not have thought she could do it, she endured the physical exertion and “did it with a smile,” said Depina-Correia, now a fourth-year apprentice electrician with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 103.

That didn’t minimize the challenges of being a woman in the industry, though. In one position, she encountered a male worker who was troublesome, she said, and who made her days so difficult to the point of pushing her to consider leaving the position.

“Overall entering a male-dominated field, I’ve just kind of erred on the side of caution when it comes to being assertive about my ideas or anything,” Depina-Correia said. “Because I guess the … overarching theme that comes from working with men is that they think we might not perform as well as men or just not be as strong as a male might be to get the job done.”

But, with the support of a friend and the Boston Union Trade Sisters, she felt reassured in her ability to succeed in the industry.

While she’s grateful for her career path, Depina-Correia said she wishes she’d known 10 years earlier that working in the trades was a viable career option. She said she has even been trying to convince her 15-year-old cousin to consider trade school because of “how good of an opportunity it is.” If young girls like her cousin were introduced to careers in the trades from a younger age, there would be more women in the industry now.

The detriment of women being underrepresented in the industry is that it results in a “lack in perspective,” she said, because diversity breeds fresh ideas and outlooks.

While men might opt for brute force while problem-solving, women “might not come in and right away hit it with a hammer or a pair of pliers. We might use leverage to get something done,” she said. Excluding women means “missing out on having more people be involved” and on the “little bit of joy” women bring to the trades.