On Nov. 5, I hopped off a bus and voted early. It was quick, convenient, and came with two stickers: one for me and one for my son.

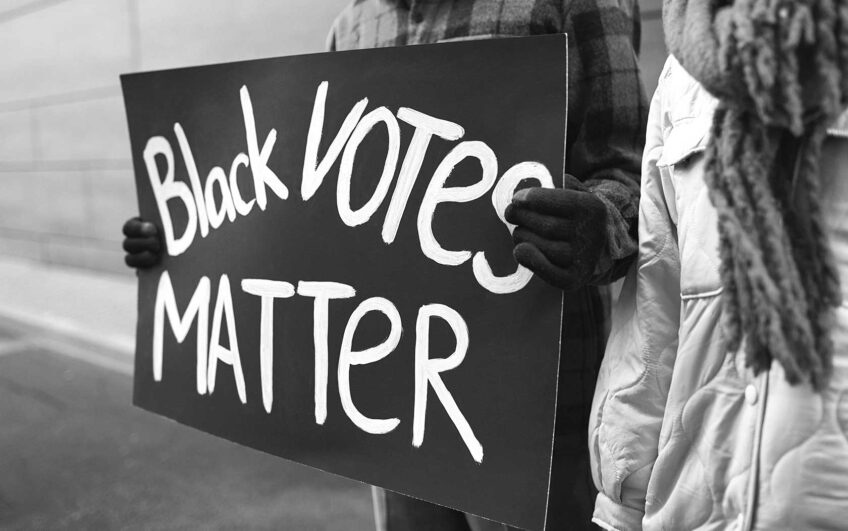

As I walked out, the volunteers (mostly elder Black women) thanked me for voting. I said, “Of course!” One of the volunteers said, “Wow, it feels like all day, I’m seeing Black men with the same reply after voting.” As an Afro-Latino, that made me smile a bit.

For years, I’ve thought about how a civic duty for some was a moral obligation for others in this country. In the week before election day, the Harris campaign was cautiously optimistic that their 100-day journey would triumph while the other side doubled down on a dark, bigoted vision for America. As waves of fascism hit countries large and small across the world, the influx felt more pernicious here, where the specter was ever-present.

Many of us knew the work we needed to do regardless of the results.

At this point, the world knows the story. The re-ascendance of Donald Trump to the presidency only confirmed the unapologetic white supremacy and patriarchy that looms over the nation. Pundits and politicians have used code words like “economic anxiety” and “wokeism” to explain the Democrats’ White House and Senate losses. However endearing, organizers rebuked the cavalcade of celebrities that came to represent the Harris campaign. (I thought Kamala Harris’ appearance on “Saturday Night Live” was perhaps her most soulful moment of the campaign.)

Others like Rachel Maddow openly wondered why Trump didn’t seem to court votes like he wanted to win. Regardless of the reasons, it bears repeating that millions of people across the country, including in so-called blue states, voted for Trump’s return with indictments and all, this time with fewer guardrails against his agenda. Fifteen million people either stayed home during this election cycle or didn’t vote for Harris at all. Yes, the Palestinian genocide played a role in the discontent. So did courting the Cheneys, who didn’t move many registered Republicans or independents, it seems.

But ultimately, the United States has a deep cultural problem, and one election won’t fix it. A country founded on enslavement, subjugation and colonial terrorism can only run from its shadows for so long.

Zooming in a bit, many of our schools and classrooms have had to contend with influences that don’t show up on standardized tests, but still affect how children see the world. Politicians over-scrutinize and under-resource schools. We’re seeing cultural shifts, too. Our schools have seen how the manosphere influences our boys, how concepts like “trad wives” set women’s political and cultural rights back decades, and how phobias and aggressions further ostracize LGBTQIA+ folks. Our social studies books have histories just like this, but diluted and dispassionate in form and function.

This dynamic is happening in multiple languages across multiple districts and student racial demographics. Our teachers aren’t all prepared to teach children to develop an internal spam filter or to moderate their addictions. Local politicians have normalized gun violence in schools. Our kids have access to watching people — like and unlike them — die needlessly with little recourse, justice, or accountability. Mayors and governors ran from socio-emotional learning and racial justice lessons shortly before election cycles.

Rather than demanding better, many of our youth have decided to idolize a person who reflects that darkness back to them. That, too, is an identity.

But I’ve been heartened by some of the reactions post-election day from educators and others, too. Unlike 2016, when people jumped into a deep depression, I’m seeing people more energized to build in community. That’s an important pivot. Some local wins in different states happened, not around party lines, but the kind of world we want to live in. I’m heartened by the examples I’ve seen from Black women who’ve insisted that other groups do better, and the Black men who were confident in letting a woman lead. It’s also exciting to engage in conversations about machismo, xenophobia, and transphobia in a way that might build a real movement.

In other words, I’m not ready to give up. Hopefully, neither are you.

Whether you were shocked at recent electoral results or knew this is who America has been all along, it means you are part of the coalition of folks who want to build a better world. And build I will with me and mine. Locally and internationally, I believe we have to walk together toward a shared humanity. A world where we do better together feels brighter than a siloed caste system, especially in the midst of unprecedented crises on our minds, hearts, and planet.

If you’re a believer, look around you and find your community. Go get your people. Grieve and mourn together. Then, find a time to build toward that bigger vision. As for me, I’ll grieve and mourn for a bit, too. I’ll think of the elders in my neighborhood, the teachers who wiped away tears to face students the next day, and the people who tried to rally others, not just for one person, but away from unapologetic divisiveness.

I know one thing: it doesn’t have to be this way. This is what it means to make politics our way of life. Steel your resolve with your people. Stay ready so you don’t have to get ready.

Billionaires and media outlets have already acquiesced to the new presidency. We don’t have to. Whatever you do, do not obey in advance. We will win.

José Luis Vilson is a veteran educator, writer, speaker, and activist in New York City. He is the author of “This Is Not A Test: A New Narrative on Race, Class, and Education.”