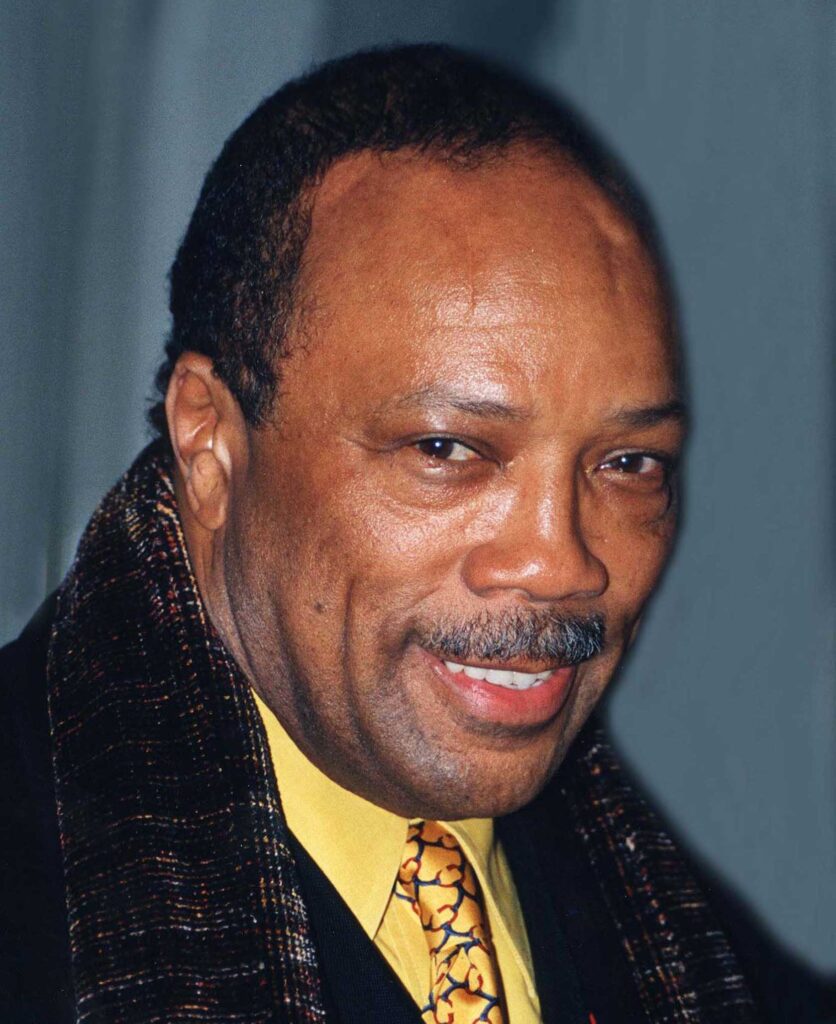

Quincy Jones, a mega force in the entertainment business and a champion of civil rights, has died at age 91.

Jones was surrounded by his family of seven children at his home in Bel Air when he passed away on Sunday from complications from pneumonia. In a career which began when records were still played on platters turning at 78 rpm, Jones kept company with presidents and foreign leaders, movie stars and musicians, philanthropists and business leaders.

He toured with Count Basie and Lionel Hampton, arranged records for Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald, composed the soundtracks for “Roots” and “In the Heat of the Night,” organized President Bill Clinton’s first inaugural celebration and oversaw the all-star recording of “We Are the World,” the 1985 charity record for famine relief in Africa.

Jones transformed Michael Jackson from a child star to the “King of Pop.” On such classic tracks as “Billie Jean” and “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough,” Jones and Jackson fashioned a global soundscape out of disco, funk, rock, pop, R&B, jazz and African chants. For “Thriller,” some of the most memorable touches originated with Jones, when he recruited Eddie Van Halen for a guitar solo on the genre-fusing “Beat It” and brought in Vincent Price for a ghoulish voiceover on the title track.

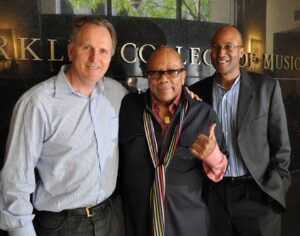

Jones at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, January, 2004. PHOTO: ANDY METTLER/WIKIMEDIA

Unfortunately, tensions emerged after Jackson’s death. In 2013, Jones sued Jackson’s estate, claiming he was owed millions in royalties and production fees on some of the superstar’s greatest hits. The California Court of Appeals reversed a $9.4 million judgment in Jones’ favor in 2017. In a 2018 interview with New York magazine, he called Jackson “as Machiavellian as they come” and alleged that he lifted material from others.

Jones’ early life was no crystal stair! He was a budding juvenile delinquent before discovering music. “They nailed my hand to a fence with a switchblade, man,” he told the AP in 2018, showing a scar from his childhood.

Music saved him. As a boy, he learned that a Chicago neighbor owned a piano and he soon played it constan tly himself. His father moved to Washington State when Quincy was 10 and his world changed at a neighborhood recreation center.

Jones and some friends had broken into the kitchen and helped themselves to a lemon meringue pie when Jones noticed a small room nearby with a stage. On the stage was a piano.

“I went up there, paused, stared, and then tinkled on it for a moment,” he wrote in his autobiography. “That’s where I began to find peace. I was 11 and I knew this was it for me. Forever.”

Within a few years, he was playing the trumpet and befriending a young blind musician named Ray Charles, who became a lifelong friend. Jones’ talent won him a scholarship to the Berklee College of Music in Boston. “Jones was there at the beginning to set the tone for Berklee to become the world leader in music education” said legendary drummer and producer Terri Lyne Carrington, who worked with Jones on his “Vibe” TV show.

Carrington, who is now founder and artistic director of the Berklee Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice, said Jones has been a constant inspiration in her career.

“For me, he’s always been a role model, and somebody I try to get inspiration from because of his ability to maneuver between all these different musical styles,” she said. “You know, that’s something that I’ve always done myself and that’s something that he’s letting me know is OK. Yes, you can be a jazz musician and flourish, and in these other areas, we can be versatile and be taken seriously and never dream too small.”

One of Carrington’s favorite quotes from Quincy is “Don’t hold a press conference saying you’re going to the moon. Hold the press conference from the moon.”

Jones left Berklee before graduating, when Lionel Hampton invited him to tour with his band. He went on to work as a freelance composer, conductor, arranger and producer. As a teen, he backed Billie Holiday. By his mid-20s, he was touring with his own band.

“We had the best jazz band on the planet, and yet we were literally starving,” Jones later told Musician magazine. “That’s when I discovered that there was music, and there was the music business. If I were to survive, I would have to learn the difference between the two.”

As a music executive, he overcame racial barriers by becoming a vice president at Mercury Records in the early ’60s. In 1971, he became the first Black musical director for the Academy Awards ceremony. The first movie he produced, “The Color Purple,” received 11 Oscar nominations in 1986, but to his great disappointment, no wins.

In partnership with Time Warner, he created Quincy Jones Entertainment, which included the pop-culture magazine Vibe and Qwest Broadcasting. The company was sold for $270 million in 1999.

“My philosophy as a businessman has always come from the same roots as my personal credo: Take talented people on their own terms and treat them fairly and with respect, no matter who they are or where they come from,” Jones wrote in his autobiography.

Brenda Andrews was the international senior vice president of Rondor Music when she worked with Jones. As the publishing arm of A&M records, Andrews and Jones had several collaborations over the years. According to Andrews, “Quincy lived and breathed music, he was a designer and creator of so many different sounds and conquered every style of music that exists. He was a musical genius!”

Andrews also mentioned Quincy’s lifelong dream was to help the United States appoint an Ambassador of Music for the world, since American music has long been an export that makes a lot of money worldwide. He apparently was in talks with Vice President Harris to make this happen.

I first met Quincy while doing my Boston TV show “Coming Together.” I literally ran into him at the Sunset Gower Studio parking lot in Hollywood. I introduced myself and told him that I had my crew from Boston, and we would love to interview him. To my surprise, he said, “Sure come back here tomorrow and don’t be late.”

We were early and so was Jones! The interview was a smashing success, and he gave me some words of wisdom that I still live by today.

Quincy Jones has left an indelible body of work for us to enjoy for years to come. He never stopped working as he just produced a documentary with Debbie Allen, “King of Kings: Chasing Edward Jones,” which is currently streaming. To his children and family, our sincere thanks go out to all of you who shared this great gift to humanity known as Quincy Jones!