‘Going to Ground’ installation honors Boston’s first Black female homeowner

Banner Arts & Culture Sponsored by Cruz Companies

At the corner of Cross Street and Hanover Street in Boston’s North End sits a steel structure, a house with no walls that is both open to the public and exposed to it. “Going to Ground,” an installation by artist LaRissa Rogers on the Rose Kennedy Greenway, pays homage to Zipporah Potter Atkins, the first known Black woman homeowner in Boston.

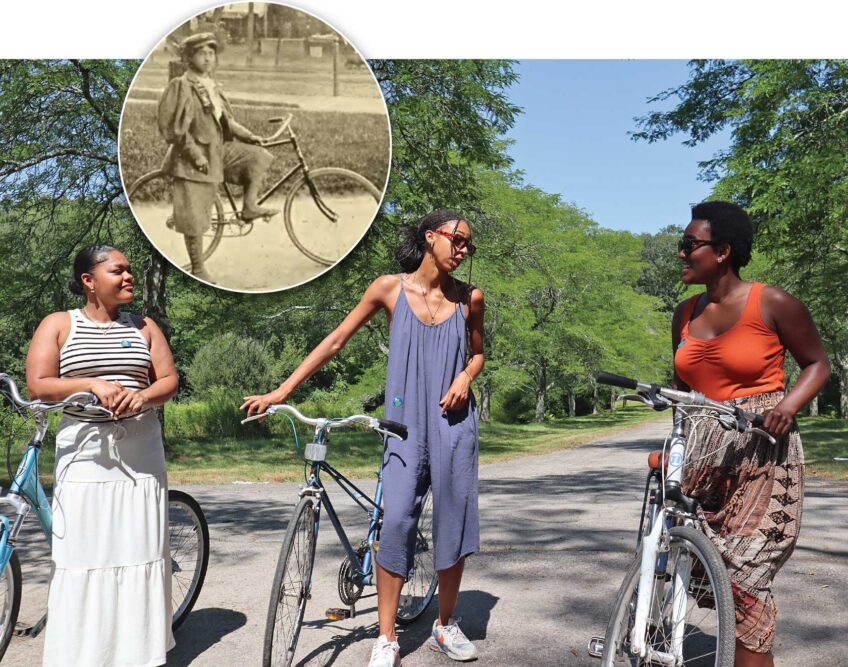

Atkins was the sole deed-holder of a home on this very site from 1670-1699. Rogers’ sculpture serves to both uncover that history — brought to light in 2010 by Dr. Vivian Johnson, professor emerita of education at Boston University — and to explore the ongoing barriers to homeownership for Black and brown communities.

Artist Larissa Rogers at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Mass., March 2024. PHOTO: OSEMWENKHAE STUDIOS

“Soil has the capacity to hold histories of trauma, and also produce life,” says Rogers. “It is a site of possibility, a living archive, a material that speaks in and on its own time.”

“Going to Ground” takes its title from and was directly inspired by author Vanessa Agard-Jones, who emphasizes the importance of groundedness as a space for thought and emotion.

The ground is particularly meaningful in Rogers’ installation. In the months prior to creating the piece, Rogers put out a call for soil from places that are significant to Boston’s communities. Soil came in from 15 different states and countries, among them Massachusetts, Virginia and Italy. Rogers used that soil to create the bricks that make up the foundation of the house installation. This incorporates local communities directly into the structure and illuminates how community is both the physical and metaphorical foundation for art and for change.

“Like soil, processes of repair move slowly,” writes Rogers in a statement. “In the wake of archival and state failures to attend/tend to Black life, we look to deepen our understanding of Zipporah Potter Atkins’ life in spaces of impossibility and imagine what’s possible through our shared attention.”

The roof of the house is designed with a scarification pattern that acts as a sundial throughout the day, casting a dramatic shadow on the ground below. The open design of the sculpture allows the community to see directly inside the piece and engage with it, but it also leaves the interior of the home vulnerable to the elements. This references the precarious state of homeownership for Black and brown communities in Boston and elsewhere in the country as well as the history of the Greenway itself. Many vulnerable communities were displaced during construction of the elevated Central Artery that eventually was torn down and replaced during the Big Dig project that led to the beautiful park we enjoy today.

Audrey Lopez, director and curator of public art at The Greenway Conservancy, says, “‘Going to Ground’ is the first project in what will be a continuing site of engagement for contemporary artists, and a larger community dialogue around honoring Zipporah Potter Atkins’ legacy and Boston’s public histories as a whole.”

The installation is currently on view on the Rose Kennedy Greenway in the North End. Throughout the life of the piece, collaborating artists Jackie Amézquita and Zalika Azim will activate the site with live performances.

“Dear community,” Rogers asks, “Can we go to ground together?”