The Jazz Urbane Cultural Commentary

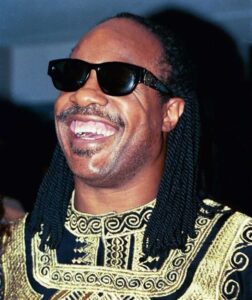

As our gem and gravity center, Black popular music culture used to be the place where we found answers and joy, a balm in our Gilead. A Stevie Wonder song, or a hip-hop anthem like “Headed for Self-Destruction” was a map. Aretha sang about “R.E.S.P.E.C.T.”

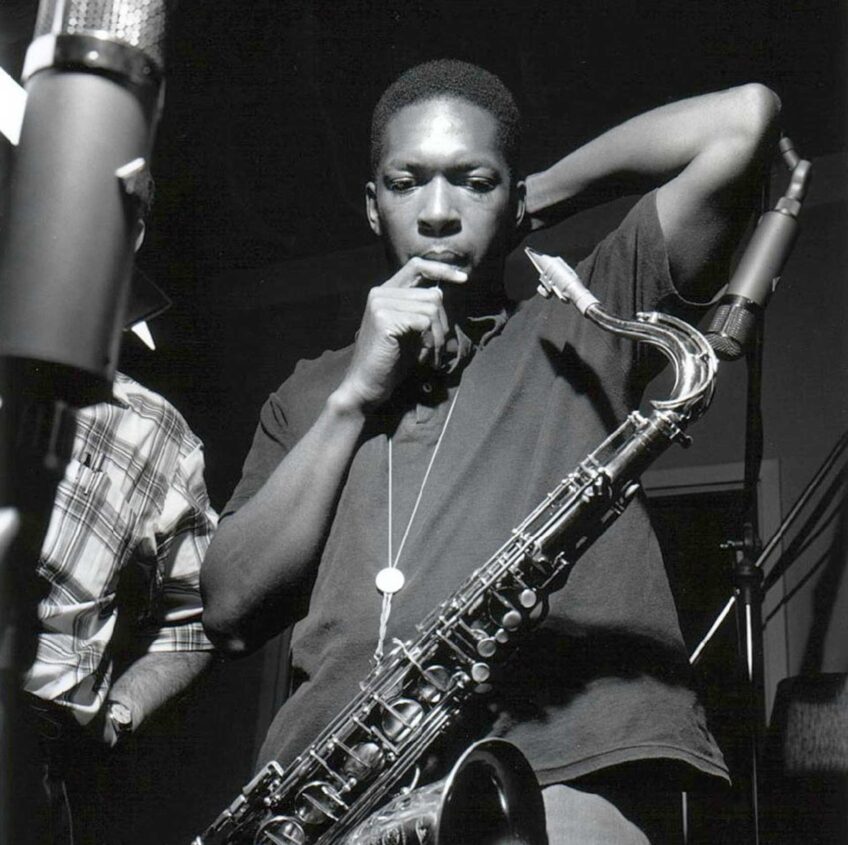

In 1984’s “The Autobiography,” Amiri Baraka wrote, “We followed John Col(Trane) … our own teaching for new definition. We heard our own search, travails, our reaching for new definition. Trane was our flag. There was a newness, defiance politically and creatively. … It was if the music was leading us.”

I’m not sure that’s the case today, but I sure wish it was. So, we are introducing a new series, pieces that are rediscovering the roots, introducing to others the reason and meaning, the gems of Black music culture. This is hugely relevant as we are looking to more fully examine what we mean by our culture(s), country, what democracy, freedom, values mean today, and how this connects in a complicated and shifting cultural terrain.

What these Black music pieces should do is raise us up creatively, ideas that can emerge and suggest reflection and then align to values, themes that move people’s spirit, imagination, thoughts and redemptive actions in our world.

That’s art with a “gem factor” in the culture.

Black music means…

Black music, as with all great art, is about moving toward human truths, universal ideals that reflect balance, order, beauty, love, justice and inspiring ideas that change people’s lives.

It has always primarily been about Black peoples’ lives and preserving culture tied to the African Griot traditions of carrying culture, creating community, critiquing culture and caring for it as well. It was always adopted and appreciated for this by all people who witnessed it. That’s why it’s a universally important tradition that we all benefit from. This includes all music in the Black African diaspora, the music of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Afro Brazilian, Jamaican and Caribbean music. In this series, we focus mainly on the six forms of Black popular music in the U.S.; Spirituals, Blues, Jazz, Gospel, R&B, Soul and Hip Hop.

What are the roots of all Black music and how did we get here today?

Africa

In “African Rhythms and African Sensibility Aesthetics and Social Action in African Musical Idioms”, Jon Miller Chernoff wrote, “The depth of music’s integration into all the various aspects of African social life is an indication that music helps to provide an appropriate framework through which people may relate to each other when they pursue activities they judge to be important or common place. … ”

A full appreciation and understanding of Black music are only possible when first looking at the full breadth of the African cultural diaspora; these include dance, music, sculpture, poetry, quilting, storytelling, instrument building, and religious practices. The African spiritual worldview and practice are the roots of Black music and African American cultural practices.

Spirituals

The Spirituals are a body of religious slave songs, created by plantation Blacks who fused together Western European harmonies and biblical stories, images, forms with pre-existing West African songs, modalities and practices creating an African American church song tradition.

Blues

The Blues are a form of secular Black music growing out of the Spirituals.

These can be thought of as plantation and Black rural songs taken on the road and to the streets in the 1890s through the 1940s and recorded. Black men were now free to roam, search for families and jobs and created this music to accompany this new life. They were known as the Bluesmen. Black women began to sing too, performing Blues in traveling musical shows and recordings. Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, and others made this Black music the most known Black popular music of its day, the prelude to Jazz.

Jazz

Jazz is the next great gem of American popular music that grows out of the urban, entertainment culture in American in the early 1900s. Birthed from New Orleans musicians, it is Black musical expression based on Blues, West African reminisces and field-shouts, mixed with European parlor and band melodies, organized for performing dances and entertaining people.

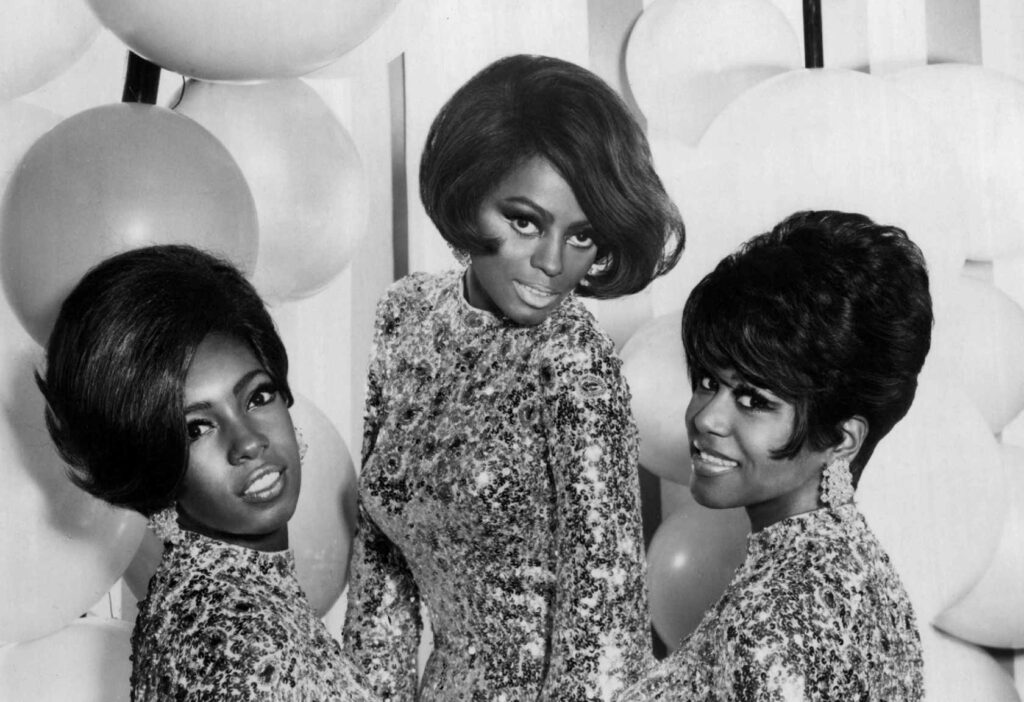

Jazz is America “growing up” and becoming modernized. With Jazz there emerges now a new identity for Black people, the modern, sophisticated “jazz artists.” Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis exemplify these traditions.

Gospel

Black gospel music in the mid-20th century can be seen as yet another outcome of the Great Black Migrations, incorporating Black rural and popular styles as well as Black cultural interests and musical styles, but heard primarily in African American churches. Gospel music became a powerful social-cultural tool within African American communities and was a major sound and style that impacted modern popular music. Many of the major singers — like Aretha Franklin, Whitney Houston, the Isley Brothers, and Sam Cooke, all voices that are staple sounds grounding rock and roll and soul — were all singers from the Black church gospel tradition.

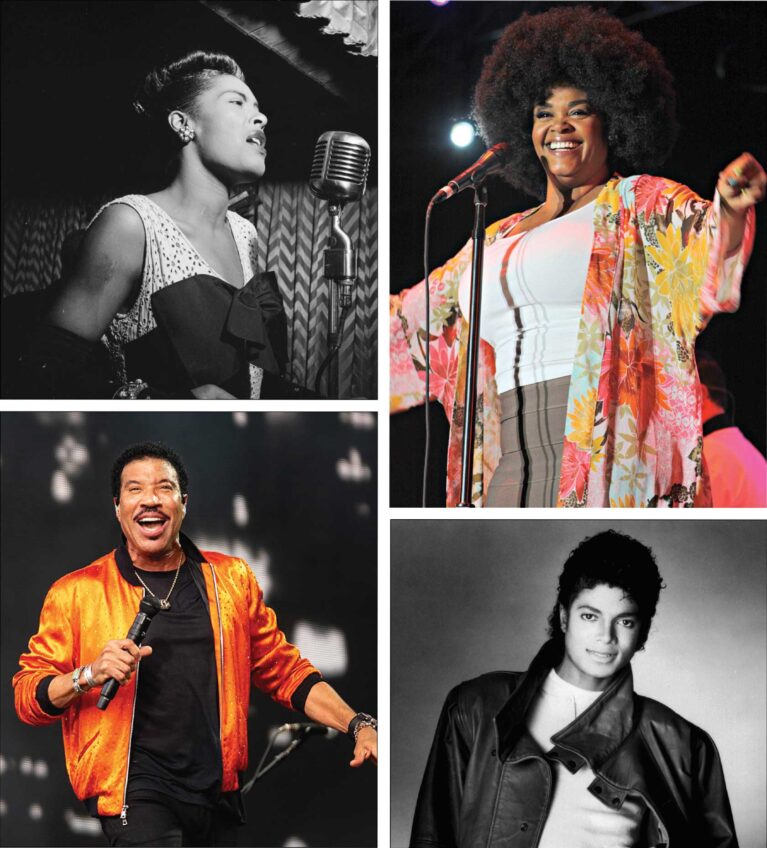

Rhythm and blues, soul and urbane contemporary black music

In 1949, Black popular music on the radio was titled, Rhythm and Blues or R&B. Think of acts like Louis Jordan, Ruth Brown, Ray Charles and Little Richard. From the 1940s and into the1960s this grows for the most part into “Soul music,”, particularly between 1965-75.

This new Black popular music represented many things: cultural and political empowerment, a musical/style category, spiritual/expression depth and meaning, race pride, and social and civic responsibility and accountability. Soul music can be thought of as the Black popular music that accompanied the Civil Rights years in America. In this turbulent period in American history, music sought to uphold a social consciousness about race, class, gender issues, police brutality, civil rights, integration, war protests and serving your common brother/sister-man. The song titles of this period tell the story though of what Soul music songwriters and performers from this period were about:

“A Change Is Gonna Come” (Sam Cooke/Otis Redding, 1965)

“Say it Loud I’m Black and I’m Proud” (James Brown, 1967)

“To be Young Gifted and Black” (Nina Simone, 1969)

“The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” (Gil Scott-Heron, 1971)

“Love The One you’re With” (1971, Isley brothers)

“Papa Was A Rolling Stone” (Temptations, 1971)

“Smiling Faces” (The Undisputed Truth, 1971)

“Shining Star” (Earth, Wind & Fire 1974)

“Wake Up Everybody” (Harold Melvin and The Bluenotes, 1975)

“Chocolate City” (Parliament/Funkadelic)

“Everyday People” (Sly and The Family Stone)

“Ain’t No Stopping Us Now” (McFadden and Whitehead 1979)

Hip hop music culture

“Don’t push me ‘cause I’m close to the edge. I’m trying not to loose my head. It’s like a jungle sometimes. It makes me wonder how I keep from going under.”

-The Message, Grand Master Flash, 1982.

Hip Hop or Rap music as it first was titled, began commercially with the release of Rappers Delight in 1979 by the Sugar Hill Gang. But the music and the culture were a movement that emerged in the consciousness of communities much earlier. Again, through sharing experiences and by diasporic connections from Jamaica to the Bronx, there emerged a new Black impulse in art. This particular expressive form grew out of neighborhood parties in the early seventies where the DJ’s spinning records used to talk with the audience during a break between records. DJs would challenge each other with capping on their opponents, thereby creating a contemporary urban debate session couched in slang word battles, rhyme schemes and humorous ways of telling a story.

Again, it’s the fall of 1979 and the first glimpse we get of Hip Hop culture commercially is heard in the now famous line, “I said a hip, hop, the hippie, the hipidipit, hiphop hopit, you don’t stop.” “Rapper’s Delight” was the first Rap record of marked success.

Conclusion

The gems are the artists and styles that people came through, ritualized by dance, singing, creating new worlds to see themselves, hear themselves, imagine themselves, wrap themselves in. That music has been critical to how Black people throughout the diaspora throughout, sounded and existed. And then the rest of the people heard it too and adapted it as their soulful songs.

One must wonder how the world too as well all joined in the Negro song, dance, ritual and all people could see their walk- talk in this music? The world got “locked into the groove and spirit” of Black music flow, song and social meaning through its all-encompassing expressions from Spirituals, Jazz, Gospel, to Soul, Funk and Hip Hop.

That’s why it is so valued, like gems, because the art matters in ways that give joy, perspectives, identity and guarantees that people sound together, exist together and are made a little higher together through the music.