As an emergency physician at Boston Medical Center in the early 2000s, Dr. Thea James saw Black and brown patients come into the emergency department forgotten by the system.

Arriving during a rise in gun violence incidents, staff in the hospital called them thugs. They bore tattooed phrases like “born to be hated; dying to be loved” and “living is hard; dying is easy.”

And then, in 2006, Mayor Thomas Menino decided something needed to change.

He tapped Boston Medical Center, which sees 70% of gunshot and stabbing victims in the city, to address the problem. The solution James, alongside her mentor, Dr. Ed Bernstein, developed was the Violence Intervention Advocacy Program.

Since then, the team has expanded from two advocates to a staff of almost 14. It has worked with over 6,000 individuals in the Boston Medical Center system. Its goal: to support gunshot and stabbing victims through recovery with a trauma-informed approach to care, while also aiming to reduce incidences of future violence.

“Our approach was to understand who these young people were, to establish a rapport of trust and try to understand what were their dreams, what were their visions of a life that they would want to live and what were the barriers to getting there,” said James, who now works as the Boston Medical Center’s vice president of mission, while continuing to direct the intervention program.

In July, the program celebrated the receipt of $370,000 in federal funding, part of the more than $13 million in Community Project Funding — formerly known as earmarks — obtained by Rep. Ayanna Pressley for nonprofit and municipal projects in her district in 2024.

At a press conference July 18, Pressley said the program has the potential to help save lives.

“Our communities need meaningful resources to save lives,” she said. “As we strive to build a more just and equitable society, it’s crucial to invest in critical programs like this one.”

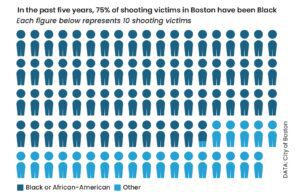

That work overwhelmingly impacts Boston’s Black communities. According to city data, within the past five years, there were 937 shootings logged by the Boston Police Department. In about three quarters of those, the victim was Black. Black residents made up over 80% of fatal shootings in the data.

The work of the Violence Intervention Advocacy Program, also called VIAP, goes beyond traditional medical interventions. Advocates serve as a resource to victims in the hospital and after, but also offer help in areas like addressing needs around access to food and other essentials, transportation, housing support and even education in an attempt to stem the tide and impacts of trauma and violence for victims and their families.

She said the work is, ultimately, about providing the people who come through the program the resources they might not otherwise have had access to.

“It’s just basic things we need to thrive and one of them is access to self-determination,” James said. “A lot of young people we encounter with these injuries cannot imagine self-determination; that is not what they have seen so far.”

Alastair Bell, president and CEO of the Boston Medical Center system, said the work is reflective of how the hospital tries to work and support communities generally.

“It centers on meeting with people where they are, working with impacted individuals to chart a path forward, including by empowering them with skills, services, opportunities so that they may return to their communities, make positive changes in their lives, strengthen others who have been affected by violence and contribute to building better communities,” he said.

After the first year of operation, the program — which had started in Boston Medical Center’s emergency department — expanded to going out into communities and has come to include family support and mental health services.

For James, the VIAP has served as proof of concept for all the other work she’s done in her career.

“It proved to me that you cannot make assumptions about who people are based upon where they come from and what their experiences are…. I always ask people all the context for what’s there, and what it would take for that to happen again,” James said. “The transformations that have occurred in the lives of so many of these young people — It’s like day and night.”

The work hasn’t been without result. According to the city’s data on shootings, in 2024, shooting incidents logged by the Boston Police Department in the first half of the year were the lowest since 2015, as far back as the dataset goes. Incidents in that time, in each year, have been declining since 2021.

The city also saw a sharp decline in homicide rates in the beginning of the year, with three recorded homicides in the first five months of the year, an over 80% drop from the same period the year previous.

It’s a trend that might be, in part, thanks to the work from VIAP, Bell said at the press conference, where he celebrated the decline cautiously. He said that while the drop is good, the statistics don’t capture the trauma and impact that violence has on an individual.

“We know that, while we’re making progress, one shooting or one death is too many, so we must continue to redouble our efforts,” he said.

Ultimately, for James, the goal of the work is simple — to level an uneven playing field.

“It’s not complicated; it’s never been complicated. There have just been barriers to some and full rein to others and you just have to remove the barriers,” James said. “We’re all human beings, and I never thought that they needed something special other than access and opportunity.”