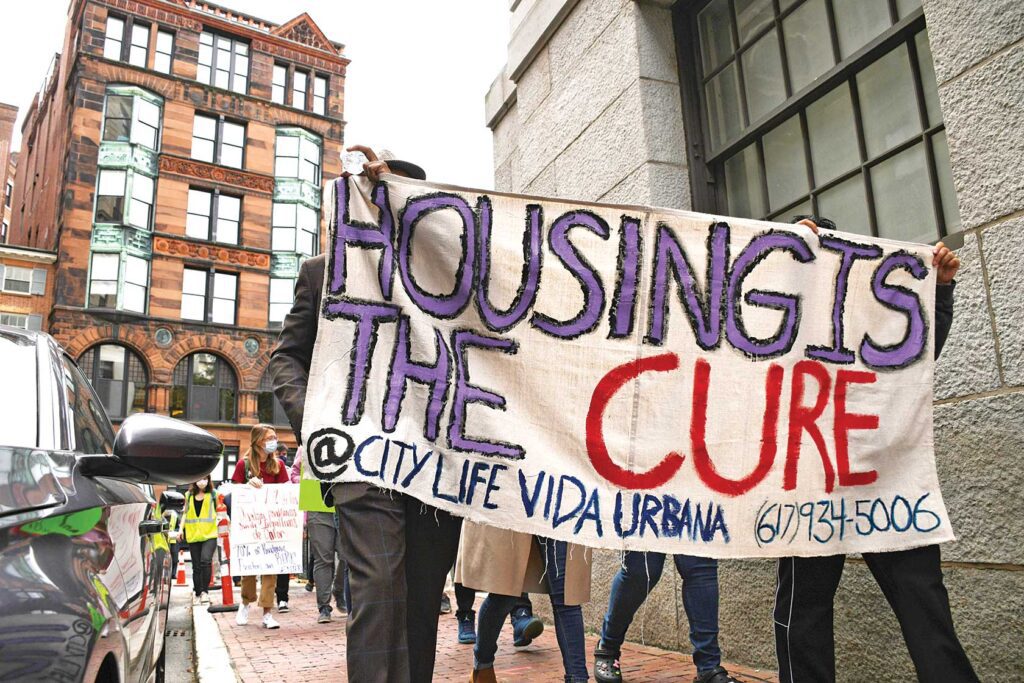

Tenant advocates look to housing bond bill to bring relief in a challenging Boston market

For Boston-area renters, high rental prices, low availability and a rising cost of living are some of the challenges that can stand in the way of stable housing.

And those issues have had an outsized impact on Black and Latino renters, who are also more likely to face discrimination from real estate agents and landlords, according to a 2020 study from Suffolk University and the Boston Foundation.

But, as the state legislative session wraps up, a bill on Beacon Hill is looking to tackle some of those issues. A housing bond bill, originally proposed by Governor Maura Healey, would make billions of dollars available to take a number of steps to increase housing production and affordability.

The exact value the legislation would authorize remains to be seen. The House passed it’s $6.5 billion version while the Senate’s would authorize $5.4 billion. Both are up from the original $4.1 billion proposed in Healey’s initial draft.

State-level action is a promising step, said Luc Schuster, executive director of Boston Indicators, the research arm of the Boston Foundation, which releases a report card for the Greater Boston housing sector annually.

“There’s certainly a growing recognition that people live, work, play regionally in Greater Boston, not just confined to one specific municipality. It’s certainly the case when most people are looking for a new home; It’s very rare that someone will only consider a new home in one specific city or town,” he said. “It means that the best solutions are going to have to happen at a higher level of government than just municipal government.”

The need for that legislation is high, said advocates working in the field.

“This is a key moment for tenants and housing justice,” said Kathy Brown, executive director of the Boston Tenant Coalition. She pointed to pieces like language in the House’s version that would open up funding to support tenants in buying a property if the landlord wants to sell, as well as policy that would allow renters to seal previous eviction records in certain cases.

For the lower-income families served by Metro Housing Boston — generally making, on average $15,000 or less per year for a family of three — supports for public housing in the bond bill are majorly important, said Chris Norris, who heads that organization.

“The housing bond bill is definitely a net positive,” Norris said. “The focus on production, the focus on preservation and repair for our public housing apartments are two things that are extremely important for the families that we work with.”

The Senate’s version of the bond bill also included an amendment that would shift who pays a broker’s fee — normally equal to one month’s rent, part of the high costs when first renting an apartment, alongside first and last month’s rent and a security deposit, that can create more barriers for potential renters.

Anne Corbin, chief operating officer at ABCD, said that change could help reduce the burden on would-be renters.

“If you can’t pay a full month’s rent, just for first month’s [rent], how do you come up with that full month’s rent to pay the broker renting an apartment?” Corbin said. “That would definitely be a burden lifted from a lot of renters. You’re really paying a broker’s fee, first month’s [rent], last month’s [rent] and a security deposit. That’s four times the amount of monthly rent.”

Under that amendment, the fee would be paid by whoever hired the broker — frequently the landlord. Boston is one of only two major cities in the country — alongside New York City — where renters are typically left to handle the fee.

Brown said the bond bill wouldn’t solve all the issues in the state’s housing landscape but could take important steps to address some of them.

“All these policies are really important,” Brown said. “You need a number of policies to address the housing crisis, to protect tenants in their housing, to help them keep their housing, and to create more fully affordable housing.”

COVID-19 worsened a struggling landscape

Housing in the city has long seen issues, but in many cases they worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, as residents lost jobs and struggled to find employment, and have yet to get better, said Corbin, who served as the director of ABCD’s homelessness and housing department during the pandemic.

“Everything was heightened during COVID and we’re still seeing that,” she said. “The folks that we serve, are still needing assistance, including those that would have never had to come to ABCD or any other service provider looking for help. Maybe they lost a job or they didn’t get employment with the same income that they may have had before.”

That landscape may be shifting, but not quickly. Schuster said that high rent prices are starting to plateau — per ongoing research for the Boston Foundation’s 2024 report card, which will be released later this year — but have yet to see declines.

“It’s hard to call this good news, but the rates of increase have slowed down. The rate of increases in home prices has really slowed, and even more so on rents, but we really haven’t seen reductions yet,” he said. “I think far, far better would be actually turning the curve in the other direction, and we just have not seen that.”

Other concerns, like limited availability, persist. He said there may be less new multi-family housing available in coming years, given the long timelines to construct them and a slowdown on ones that are already permitted.

Corbin, too, highlighted the need for more housing — especially affordable options — across the city. One challenge she has seen, she said, is a narrow scope for who falls under the parameters for affordability.

“Although the cost of living in Massachusetts is extremely high, the income eligibility for some of the affordable housing units is not high,” Corbin said. “If you don’t fall in the lowest of the low, then you’re not eligible for a subsidy. Right now, you can make $80,000 and still need assistance, paying for rent.”

Heightened barriers for renters of color

Barriers in the housing market impacts renters across the region, but renters of color have faced increased challenges.

According to the 2023 Greater Boston Housing Report Card, Black and Latino renters were more likely to experience a cost burden — having to pay more than 30% of annual income on rent — than their white counterparts.

That report found that 55% of Black renters and 57% of Latino renters experienced cost burdens when it came to housing. Nearly 30% of both demographics were severely cost burdened, meaning they had to spend more than half their income on rent.

In contrast, 49% of all renters in the Boston area experienced a cost burden while, among white renters, that number was about 46%.

And some of the challenges faced by renters of color are more direct. A 2020 study from Suffolk University and the Boston Foundation found that Black renters experienced instances of discrimination — like being shown fewer apartments or being ghosted by real estate agents — in 71% of undercover cases tested by the researchers.

The study also found that individuals with Section 8 housing vouchers also experienced discrimination, with agents dropping communication or outright refusing the apartment, sometimes describing voucher holders as less-attractive applicants.

Norris, at Metro Housing Boston, said the organization has a fair housing department that regularly hears from residents being turned away by landlords.

“We still receive calls regularly about landlords who say they won’t accept a voucher for payment, or they have lead paint, or they would prefer not to have kids,” he said. “Oftentimes, [it] doesn’t even get to that part. Oftentimes, what happens is folks are ghosted.”

But renters aren’t left to face the landscape all on their own.

For lower-income residents, Metro Housing Boston offers programming around homelessness prevention, housing stability and economic security.

Organizations like ABCD offer housing counseling services and moderating conversations with landlords. The organization also connects potential renters with services like Housing Navigator Massachusetts, an online database of income-restricted rentals statewide.