In the face of rising sea levels, art efforts are rising to the challenge

Installations explore human impacts on the environment

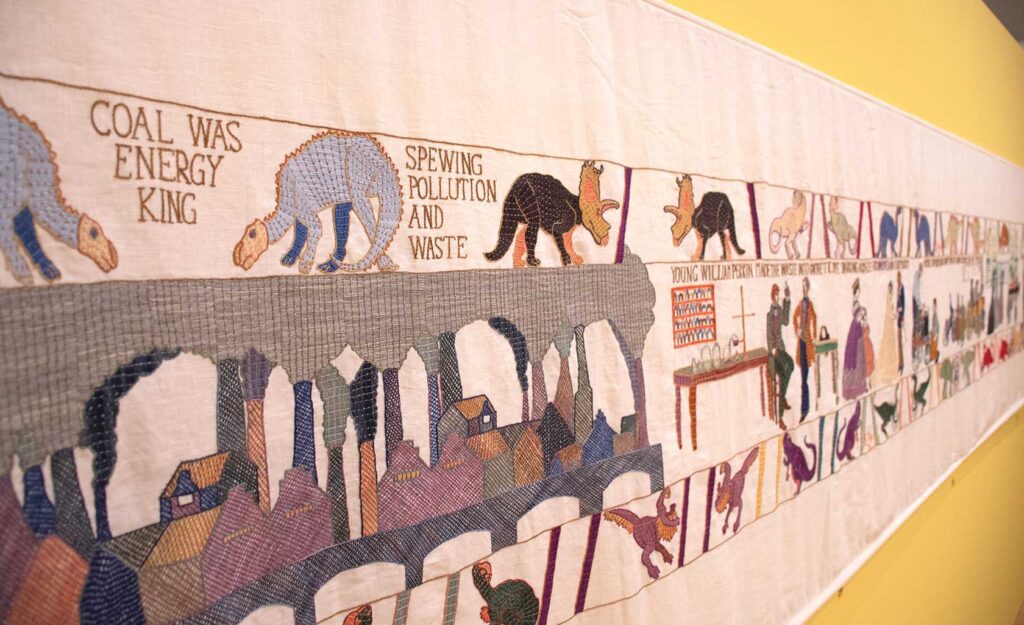

At a little museum on Huntington Avenue, 200 feet of linen, lined with colorful images of dinosaurs, depicts the history of fossil fuels from the Triassic Period to the late-1900s when researchers showed carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere were steadily rising.

The last six feet of the artwork, without words, shows the impact of oil spills and other pollution on people, wildlife and the environment.

This “Black Gold Tapestry,” a hand-embroidered artwork by artist Sandra M. Sawatzky, is part of “Displacement,” a new exhibit at the MassArt Art Museum that opened at the end of June, exploring how humans have affected the environment and how the environment is responding.

Stitched figures illustrate the impact of climate change in Sandra M. Sawatzky’s “Black Gold Tapestry,” part of an exhibition on human environmental impacts at the MassArt Art Museum. PHOTO: Avery Bleichfeld

As organizations across the city work to meet climate goals that would sharply limit their emissions in the coming decades, exhibitions like “Displacement” have a role to play in communicating about climate change and the impacts it can pose, said Amy Longsworth, executive director of the Boston Green Ribbon Commission.

“Art can stimulate discussion. It can poke and provoke and ask questions and scare you and delight you. It gets to your emotions in a way that a report can’t,” Longsworth said.

That ability of art isn’t unique to discussing climate change, though conversations around climate and environment are one important outlet, said Annie Lundsten, a co-founder of the Experience Alchemists, an experience design and consulting firm.

“Art always has played a role in helping us, as humans, think differently about the world around us,” she said. “Whether it’s climate change or the political landscape or how we interact with each other.”

It’s a role that comes from art’s ability to evoke emotion in a way that simple data or words can’t always do, said Silvia López Chavez, a local mural artist whose work has included images focused on climate and rising sea levels.

“I think art has the ability to bring it home, to bring some clarity around certain topics in a way that is understood by many audiences,” López Chavez said. “I think that in particular, it’s being able to dissect or focus on a specific area in small bites so people can understand it.”

An image of David Ortiz illustrates the effects of climate change in Silvia López Chavez’s mural at Fenway Park. PHOTO: CELINA COLBY

Sometimes that work involves translating data into a more immediately recognizable form. A 2022 project she did at Fenway Park, featuring an image of former Red Sox player David “Big Papi” Ortiz, showed the two feet that sea levels are expected to rise in the area by the year 2070.

That mural was one of six temporary public art installations across the city aiming to draw attention to the climate and environment as part of the Action Pact campaign, an effort organized by the Green Ribbon Commission — with support from Lundsten’s Experience Alchemists — in partnership with institutions like the Museum of Fine Arts, the Museum of Science and the Red Sox.

But, for López Chavez, more important than visualizing data is telling a story.

“My hope is that that the more time you spend with the imagery, the more you understand what’s happening, and the more you learn about what the message is,” she said.

For example, another mural by López Chavez in East Boston, called “Rise,” shows a mostly-submerged female figure surrounded by natural elements, like seaweed and a North Atlantic right whale, as well as human-caused impacts in oceans, like netting and floating plastic.

“She’s overwhelmed by water, but at the same time she’s calm, and it looks like she’s using her hands in action, she’s doing something about what happened. … You start questioning, ‘Why is she doing that?’” López Chavez said of that work, which was part of the international Sea Walls art program.

Other cultural institutions in the city have taken a stab at the work as well.

The New England Aquarium, through both its public-facing outreach and its research, focuses efforts on conservation and climate change. In November, the aquarium displayed a public art photo series highlighting locations along the city’s waterfront and encouraging connection and engagement with those spaces to support resilience efforts.

Similarly, other organizations like the Arnold Arboretum or the Zoo New England pay similar attention to conservation efforts.

But in other institutional settings, where environmental messaging isn’t necessarily expected to be baked into the mission, it’s a process that can be slow to develop.

When she first joined the Green Ribbon Commission in 2016, Longsworth said, she had lofty goals of jumping into the fray and convincing museums and cultural institutions to make immediate changes.

Sandra M. Sawatzky’s “Black Gold Tapestry,” lines the walls at the MassArt Art Museum as part of an exhibition on human environmental impacts. PHOTO: Avery Bleichfeld

“I was like, ‘I know — I’ll just tell them we exist, and then they’ll do exhibits about climate change. It’s so simple,’ and that was hopelessly naïve,” she said. “I mean, these are world-class organizations. They take five or 10 years to plan an exhibit. They borrow from all over. They do not listen to people like me telling them they should do things about climate change.”

But Longsworth said the Commission began to do work in helping to develop educational programs focusing on climate change at cultural institutions, an area where she said there’s been more progress.

When institutions do develop exhibitions about climate and environment, it’s also a process of exploring what art and what exhibitions about the topic mean.

Lundsten, who has a background working with museums and other institutions, said it’s easier for contemporary art that can address the topic more directly and that sometimes exhibits ostensibly about climate might just focus on nature.

“If you’re talking about plants and animals, that’s awesome and lovely, and it’s great to draw people’s attention to the natural world, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re opening discourse or getting the topic of climate change to the top of the top of the pile,” she said.

Meanwhile, as cultural organizations in Boston explore how to communicate about climate change in their unique ways, the same organizations face pending deadlines to reduce their own emissions.

Under 2021 regulations passed by the Boston City Council called the Building Emissions Reduction and Disclosure Ordinance — or BERDO — all buildings greater than 20,000 square feet must decrease their emissions in five-year increments to reach net-zero targets by 2050.

The regulatory push is leading local institutions to reexamine their environmental impact. López Chavez pointed to efforts at Fenway Park around plastic waste the ballpark has engaged in in addition to communication efforts like her mural.

According to reporting from the Boston Globe, other institutions like the Isabella Stewart Gardener Museum are looking to implement cleaner energy sources and more energy-efficient appliances like LED lightbulbs, while others like the New England Aquarium are cleaning and recycling resources like water in exhibits to minimize use.

That work comes as part of climate action plans developed with assistance by the Green Ribbon Commission. Longsworth said the effort started with cultural institutions, but the commission is expanding to other companies and organizations, as groups across the board have to adjust to BERDO requirements.

“We cut our teeth on the cultural institutions, we welcome cultural institutions, but honestly now, with BERDO in place, every single institution in Boston needs a climate action plan,” she said. “We take all comers.”