As drivers sought to head home or to evening activities on June 7, the music and chatter of buskers at Faneuil Hall mixed with the chants of youth activists as protesters shut down the street below City Hall, calling on Mayor Michelle Wu to preserve updates in the city budget that would increase access to youth jobs and housing.

The protesters from the Youth Justice and Power Union, alongside supporters, shut down Congress Street for about two hours, setting up tents in the road, decorating the pavement with chalk and calling into a megaphone for preservation of the $4.5 million that the City Council voted to move from the Boston Police Department budget into employment programs for youth, as well as rental subsidies and community land trusts. The budget overall totals at about $4.6 billion.

The effort, which nearly ended in the arrest of protesters as officers marked off the space with yellow police tape, ultimately had little effect. Mayor Michelle Wu largely shot down the budget amendments that the activists were supporting Monday.

In her response, Wu did keep a $750,000 increase in youth employment out of the $2 million proposed by the Council as well as an additional $500,000 for housing.

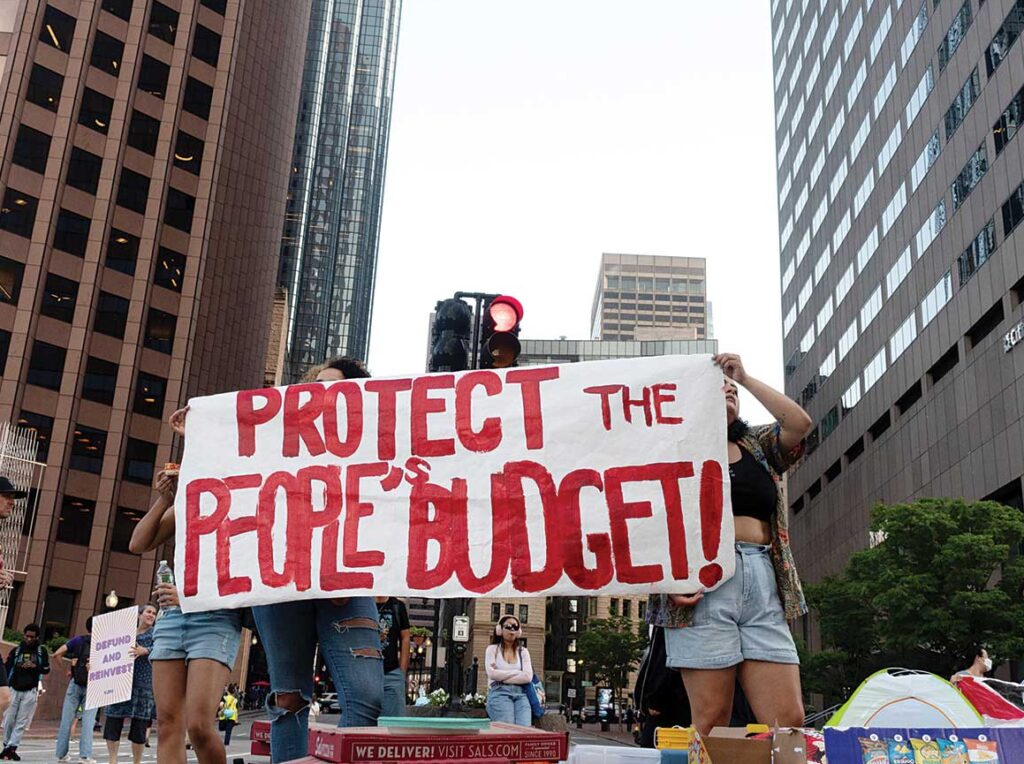

A protester writes in Congress Street during a youth-organized rally, June 7, in support of City Council budget amendments that would redirect

some police funding into housing and youth jobs. BANNER PHOTO

She also upped the police budget by an additional $20 million, from the $454.9 million she had included in her April budget proposal, to $474.3 million in her response to the Council’s adjustments, a change that she credited to contracts the city recently settled with two police unions, according to reporting by the Boston Globe

The protesters from the Youth Justice and Power Union said that increased funding for youth jobs can help provide better support for families who might rely on that income to the household.

Victoria White, a youth leader with the group, said her job made it possible for her to pay for ride shares to get to school when she fractured her foot and had trouble taking public transportation.

She said she doesn’t have to use the income from her job at the Youth Justice and Power Union to pay for a lot in her household, but she knows of others who do.

“My friends have to pick between lunch on their dinner table or lights in their house and it’s hard to see that, especially too when we live in such a rich city,” White said. “It’s hard to see that $50 million are going towards the police instead of at least just 2 million going to youth jobs to support us.”

They also spoke in support of reduced funding for police, out of concern that the policing system fails to properly support Black and brown communities.

“In my community, we know that affordable housing and just mental health crisis response keep us safe, not police,” said Alexa Santana, a youth leader at Youth Justice and Power Union. “There are so many youth wishing for a home and a community that cares. People deserve to have resources in their communities. People deserve real safety, not police.”

The $4.5 million the City Council moved from the police budget was pulled from a $50 million increase in funding to the department from last year.

Youth Justice and Power Union organizers rally below Boston City Hall June 7 in support of budget amendments that would increase investments in housing and youth jobs. BANNER PHOTO

Protesters also pointed to underspending by Boston Police around its permanent employees, something also noted in a May letter to fellow councilors by District 4 City Councilor Brian Worrell, who chairs the Council’s Committee on Ways and Means and leads the budgetary process.

“$50 million [to Boston Police] but there are youth who can’t get jobs to support their families and put food on their tables,” said Joaquim Lombos, a youth leader with the Youth Justice and Power Union. “The money not being used by the police can easily be divested and used to fund community problems in Boston, specifically youth jobs.”

In a post on X, formerly Twitter, the Boston Police Patrolman’s Association said it supported Wu’s move to restore the funding the City Council had reallocated.

“We applaud Mayor Wu for not only prioritizing public safety, but moving to fully restore any irresponsible cuts to the police budget by a City Council seemingly more concerned with playing politics instead of providing the highest levels of public safety to the people of Boston,” the group posted.

Wu’s action is the latest step — and one of the final ones — in the city’s budgetary process, which was updated in 2021. Under the current process, the mayor proposes a budget that is sent to the City Council to approve, adjust or reject.

Following a ballot question in 2021, the City Council now shares authority over the budget with the mayor, with the ability to make wider changes to the proposed budget, including increases to existing line items or the addition of entirely new line items that previously was outside of the scope of their powers — so long as the budget stays below the total amount proposed by the mayor.

After the City Council adjusts the budget — the council passed its budget on June 5 in a 10-3 vote, in all reallocating about $15 million — the budget goes back to the mayor’s desk to approve or veto the changes. The City Council can override the mayor’s veto with a two-thirds majority.

Two of the 10 council members who voted in favor of the changes would have to flip their vote and not approve the override to keep Wu’s veto in place.

Youth organizers dismantle their protest in Congress Street, June 7, after police put up yellow tape and threatened arrests in response to a rally that stopped traffic for nearly two hours. BANNER PHOTO

The protest comes as groups across the city are pushing for greater citizen involvement in the budgetary process.

Also in 2021, under the same ballot question that shifted City Council’s power around the budget, voters approved establishing a participatory budget process in the city that would require the mayor set aside money in the budget to be allocated more directly by residents.

After a slow process to establish the city office responsible and put together the procedure, this year will mark the first time residents will be able to voice their thoughts on how that chunk of money should be spent.

“This is a process where people actually have decision-making power,” said Eliza Parad, co-coordinator of the Better Budget Coalition. “Every other city process is essentially asking for input from residents, where the city has somewhat of a plan and they’re asking for input on certain elements. Participatory budgeting fully puts decision making in the hands of the residents and when it comes to resources, that’s critical.”

In her budget, Wu set aside $2.1 million for participatory budgeting. Members of the Better Budget Coalition wanted a full 1% of the city budget, about $46 million.

Supporters of the participatory budget process view it as a more directly democratic process, that will also allow a greater selection of residents to say how they think the city should be spending it budget. The process allows for input from residents as young as 11 and also includes undocumented immigrants.

“It really brings all voices to the table to think about how to use limited resources best to meet your needs,” Parad said.