Efforts to close outdoor recreation diversity gap could bring health, conservation benefits

Mardi Fuller credits her love for the outdoors to her parents — Jamaican immigrants who were persistently outside, if not hiking and climbing — as well as school, church and camp outings growing up, which introduced her to the American flavor of recreation, that branded way of getting outdoors that means spending $1,000 on gear to camp in the woods.

But when Fuller gets out into the woods, she and other recreators of color tend to be underrepresented, part of what she sees as a longstanding legacy.

“People of color were never really part of the narrative that the US created around the outdoors,” she said. “There’s just a general deficit that we’re operating at where there’s a lack of sense of belonging in outdoors spaces.”

That gap has an impact. While those leafy green woodlands scored with birdsong and cool waterways filled with the splash of paddles provide fun summer opportunities, they also offer a host of physical and mental health benefits that communities of color, who see lower representation in outdoor recreation, miss out on.

New moves by the state government aim to grow the outdoor recreation industry and bring a more diverse selection of recreators into the space.

“One of the goals of my office is to try to make Massachusetts one of the most, if not, ideally, the most welcoming, inclusive, diverse and accessible places to come [and] recreate,” said Paul Jahnige, director of the Massachusetts Office of Outdoor Recreation. “I think we have some work to do there.”

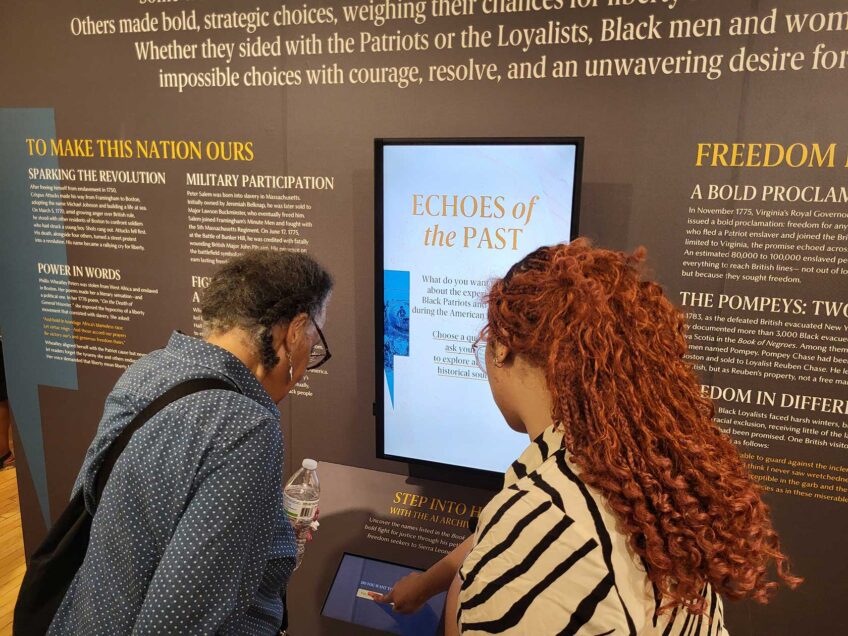

Participants learn to fish during an outing at Camp Sewataro in Sudbury organized by Elevate Youth and the Boys and Girls Club of Dorchester. PHOTO: Elevate Youth

In May, Massachusetts joined a coalition of state outdoor recreation offices, called the Confluence of States.. The coalition’s Accords, its guiding document, outlines goals around conservation, workforce training, economic development and public health.

When Massachusetts joined the Confluence, it adopted a new guiding pillar focused on reducing barriers to access and promoting safety and inclusion in outdoor recreation.

Those barriers often include limited time, difficulty accessing locations that are often only accessible by car, high gear prices, and the persistence of some gatekeeping in recreation communities — limiting factors that are nothing new, said CJ Goulding, executive director and co-founder of Boyz N The Woods, a national nonprofit that runs outdoor retreats for Black men.

“I’m not going to be saying anything radical by naming the list of barriers, because I think even at this point, knowing what the barriers are isn’t a mystery,” he said.

Fuller, an advocate for more diversity in the outdoors, said the gap in access stems from a longstanding culture around the outdoors that has left people of color out.

What to do about addressing the barriers is different question.

Through its retreats, Goulding’s group looks to bring Black men into the outdoors, not just to generate comfort in the space, but to help become their best selves. That process includes working with mental health professionals during the retreat, in addition to participating in outdoor activities.

“We’re building spaces of community, we’re building stronger mental wellbeing for the men who join and introducing them to new outdoor spaces and outdoor activities,” he said.

And the state is pushing for its outdoor recreation to be a part of the push. A relatively new state entity, the Massachusetts Office of Outdoor Recreation was established in late 2022 — Jahnige joined the team in September 2023.

It comes as part of a relatively new trend nationwide; the first office focused on outdoor recreation was founded about a decade ago in Utah

But Massachusetts’ office has started work on growing the industry here, including supporting more diverse recreation.

In April, the state announced $167,000 in grant funding to 21 organizations — including, in part, funding a Boyz N The Woods along the coast near Essex, Massachusetts — to run events across the state focused on inclusive and accessible outdoor recreation.

Participants learn to cross country ski at the Weston Ski Track during an outing organized by Elevate Youth and the Boys and Girls Club of Dorchester. PHOTO: Elevate Youth

“Events are a great way to bring new people in, to introduce them to outdoor recreation, outdoor recreation spaces, and then also be able to communicate with those participants,” Jahnige said.

Jahnige called the grants one of the office’s early actions, but said the office has more projects in the works to address the barriers he sees standing between underrepresented communities and outdoor recreation.

He outlined goals of highlighting spaces that are accessible by transit as well as supporting language access by diversifying languages used on signage and websites for outdoor recreation resources.

The state’s work is guided by an awareness of a so-called “nature gap,” he said. According to a 2023 report by the Outdoor Industry Association, Black participants made up about 9% of the outdoor participant base but almost 13% of the United States population.

And that gap doesn’t just limit the leisure elements of outdoor recreation. Studies have shown exposure to green spaces can present numerous health benefits.

Day to day, less green space can also mean more heat trapped by surfaces like asphalt and concrete that can contribute to urban heat islands. It’s an issue the city has been working to address through developing an urban forest plan and a plan to mitigate heat impacts.

“If there are benefits to outdoor recreation that go beyond just having fun, to either economic or public health, you know, it becomes an environmental justice issue,” Jahnige said. “So, how do we make sure that the benefits of outdoor recreation accrue to everyone in the state, regardless of economic status or racial background?”

The Confluence of States, too, includes both conservation efforts and public health goals in its five guiding pillars.

Fostering a love of nature could also be an important step to growing support for conservation and preservation movements, said Fuller, for whom environmental justice and outdoor recreation are intrinsically linked.

“People need to feel a sense of belonging and comfort outside to feel a desire to protect nature, and a sense of wanting to have ownership of solutions,” she said.

Advocates say that, as work to diversify the outdoor recreation industry develops, it’ll have to be based on partnerships. Fuller said that any work from the state should be done in collaboration with local communities.

“It’s joint ventures, but I think community really needs to be at the center of it so that programs aren’t created by people who have no sense of what a community wants and how they want to be outside,” she said.

Those partnerships, too, can open doors to opportunities that might not have otherwise been possible. A six-year-long collaboration between the Boys and Girls Club of Dorchester and Elevate Youth, a Boston-based nonprofit focused on engaging young people in the outdoors, has brought programming for local kids outside the walls of the Boys and Girls Club’s building.

“Our programming is really based inside a building,” said Mike Joyce, senior vice president of operations at the Boys and Girls Club of Dorchester. “It’s facility-based and you know, it’s successful and it works, but to be able to jump in, [Elevate Youth] over the years has been able to get our team off site to experience outdoor activities which we typically wouldn’t offer.”

That kind of partnership will be key to closing the gaps in access, said Alec Griswold, founder and former executive director of Elevate Youth.

“No one organization, no one person, is going to address this issue,” Griswold said. “It needs to be a collaborative approach and the more voices — and the more diverse voices — that are leading this advocacy I think the better.”

Two fishing day trips to Brookline Reservoir, offered by the two organizations in conjunction, will use more of the state grant funding to connect youth and their families with local outdoor opportunities.

Those outings are designed to be a gateway to the outdoors, not a one-and-done experience, Griswold said, with a beginner’s take-home fishing kit in addition to the transportation and instruction.

It also is an opportunity to showcase ways to engage with outdoor recreation locally. Griswold pointed to spaces like Franklin Park or local beaches as an easy way to connect with nature.

In a separate conversation, Fuller said she likes spending time in the Blue Hills Reservation, south of Boston, though she said that public transportation offerings to the site are lacking.

Chaya Harris, Elevate Youth’s new executive director, also called for expanding the concept of outdoor recreation to things that can be done in Boston, even if it doesn’t involve a miles-long hike in the woods.

“Our communities are doing things like gardening and farming and bike rides in the city,” Harris said. “All of those things should be elevated and make sure that they get the attention that they deserve as well.”