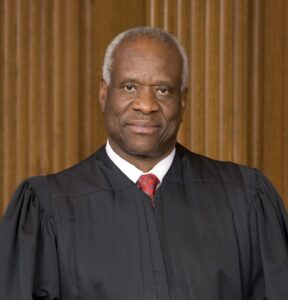

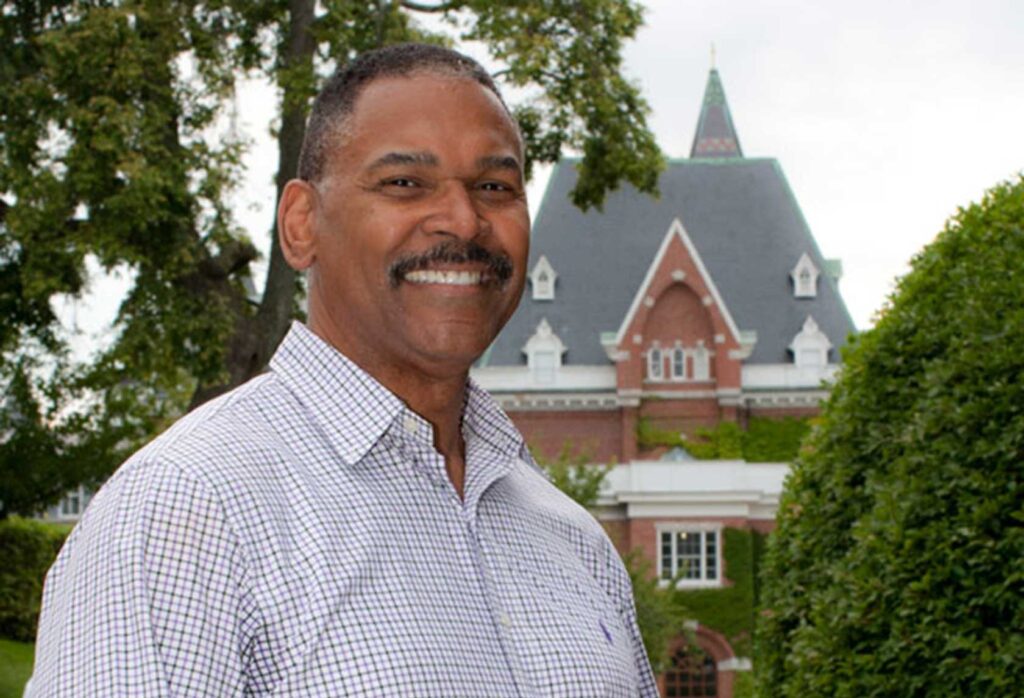

Roxbury lawyer Eddie Jenkins has distanced himself from Clarence Thomas, who was a friend and classmate at the College of the Holy Cross, because of the justice’s decisions on the Supreme Court.

Last December, Jenkins sent Thomas a 12-page missive titled, “A Letter to a Brother That I Once Thought I Knew,” that reminisces about their relationship, from their days collaborating as Black student activists on the Worcester campus and post-graduation disagreements about civil rights law to the U.S. Senate battle over Thomas’ nomination and his string of court decisions based on a narrow reading of the original Constitution.

“What is troubling for Black Americans is that during your thirty-one (31) years of seemingly ‘originalist philosophy,’ we as innocent bystanders are directly impacted by your manifesto of opinions discrediting and weakening any groups or persons who opposed your nomination, including women, Black people, Democrats, and progressives,” Jenkins writes.

The letter, which Thomas did not answer, at turns strikes a tone of disappointment and disdain while holding out a faint hope someone Jenkins has known since 1968 might change his judicial stance. Parts of the letter read like a legal brief with case citations and footnotes, while others contain literary references or express Christian beliefs in compassion for others and the possibility of redemption.

Jenkins reveals that long before his Supreme Court nomination, Thomas argued in private debates that Brown v. Board of Education, a unanimous court decision in 1954 that outlawed segregated schools, was “wrongly decided.”

“I often listened countless times to your criticism of how the Brown vs. Board of Education case was wrongly decided,” Jenkins writes. “Interestingly enough, you ignored the disparate resource allocation between Black and white public schools but focused on the black-and-white doll experiment wherein the Black child chose the white doll. You thought there was little or no psychological impact, which was an early indication of your seemingly race-neutral blinders.”

In an interview, Jenkins said Thomas first expressed that opinion while he was an aide to former Sen. John Danforth, a Republican from Missouri, from 1979 to 1981 — a decade or more before George W. Bush nominated Thomas to the Supreme Court. The conversations occurred in Washington, D.C., where Jenkins was working for the U.S. Department of Labor.

Potential nominees to the Supreme Court are carefully vetted, suggesting members of the Bush administration and possibly the president knew Thomas opposed one of the court’s landmark decisions, given that a friend like Jenkins knew. Once seated on the court in 1991, Thomas replaced Thurgood Marshall, who as a NAACP lawyer had argued the Brown case before the court.

Jenkins said he sent the letter because of the cumulative impact of Thomas’ conservative decisions, but particularly his concurring opinion in the 6-3 decision last June that overturned precedents going back to 1978 allowing colleges to consider race in admissions, one form of affirmative action.

In that opinion, Thomas cited a dissent in Plessy vs. Ferguson, the 1896 case that endorsed racial segregation as “separate but equal,” a doctrine that the Brown decision overturned.

“That’s what got me,” Jenkins said in the interview.

Thomas did not respond to a request for comment submitted through the public information office of the Supreme Court.

Thomas and Jenkins were among 19 Black students that a Catholic priest at Holy Cross, John E. Brooks, recruited to the Jesuit school, making Thomas a beneficiary of affirmative action.

Jenkins said in the interview he debated whether to send the letter and, then after he did and received no response, whether to make it public.

“Who would have ever thought that this brother coming from the kind of background he came from would ever have that kind of gall to have these kinds of opinions the way he does?” he explained, referring to Thomas’ upbringing in segregated Savannah and nearby Pin Point, Georgia. “So I decided to release the letter and to let it marinate a little bit.”

His other motivation was to sound a warning about Black individuals like Thomas.

“There [are] a whole lot of people who have been given a tremendous amount of power and opportunity, and they’re no different than him,” Jenkins said. “Everybody has somebody in their network that’s like that, and it’s not because they’re Republican. It’s because they have no heart for the people, that they really and truly represent, in an equitable way.”

Jenkins said he decided to share the letter with the Banner, which publishes the full text in this edition, because its readers live near where he does. In the past, some local associates have heard Jenkins defend his college classmate or give him the benefit of a doubt.

The Banner asked Jenkins what he would say to longtime Thomas critics who might wonder what took Jenkins so long to disassociate himself from his college classmate.

“When you know someone for a long time, there’s ebbs and flows in how you have communications and relationships,” he replied. “You always have a feeling deep down inside there’s a possibility of change.”

The relationship between Jenkins and Thomas has had it ebbs and flows. They started out close friends who addressed each other with the nicknames “Jenks” and “Couz” at Holy Cross.

“We hooked up almost the first couple days he was there. I became one of his closest friends,” Jenkins said. He later introduced Thomas to his first wife, Kathy Ambush, who was from Worcester.

After graduation, Jenkins became a professional football player before going to Suffolk Law School. Thomas went straight to Yale Law School and worked for Danforth in Missouri before joining his staff in Washington.

Jenkins and Thomas kept in touch through former classmates until the debates over the Brown decision strained their relationship. Jenkins said they did not speak for 10 years until, at the urging of other classmates, Thomas invited him to lunch at the Supreme Court in the early 2000s. They aired their differences over the meal, while Thomas pointed out he had two or three Black clerks working for him.

“From that point on, we just interfaced at Holy Cross” or when Thomas came to Massachusetts to speak at the New England School of Law or Southern New England School of Law, now UMass School of Law, Jenkins said.

The last time the two men saw each other was in 2008 when both attended an event commemorating the 40th anniversary of the founding of the Black Student Union at Holy Cross.

Jenkins, 73, practices what he calls “community law” in Grove Hall, helping people with “everyday problems” or making referrals to other lawyers. He has chaired the state Alcoholic Beverages Control Commission and served as chief diversity and civil rights officer for the Massachusetts Department of Transportation. He has run unsuccessfully for Boston City Council and Suffolk County district attorney.

His letter to Thomas concludes with a chilling suggestion about what may happen when the justice faces “one final ‘supreme hearing’” and is asked, “What did you do with the talent and power that was given to you to help your brothers and sisters?” His presumed response elicits “a deep guttural laugh” from someone other than God.