Banner Sports Sponsored by the Patriots Foundation

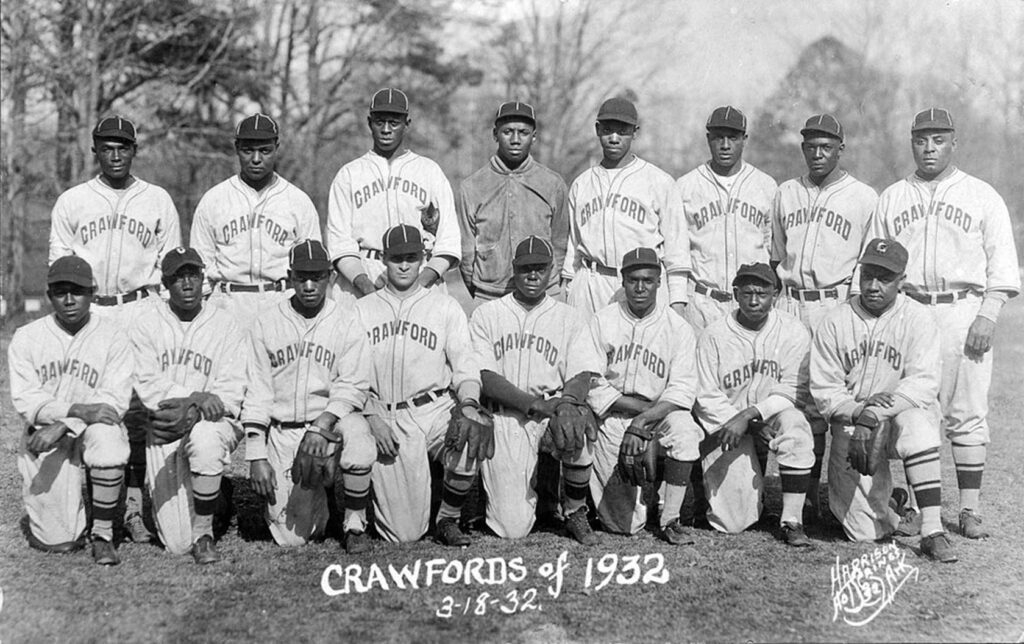

The words “justice delayed is justice denied” seem appropriate for this story, which centers on Major League Baseball’s attempt to right a century-old wrong. I am speaking about MLB’s recent announcement that it will incorporate the statistics of the Negro League’s baseball legends of the past into its official record books. The sad irony of this story is that it took over 100 years to bring to light a lost chapter in the history of America’s Grand Old Game.

For most of my adult life, I have tried to tell the stories of Black men named Josh Gibson, “Cool Papa Bell,” Martin Dihigo and far too many others to list here, who were some of the greatest baseball players of all time.

My father and other relatives, who were eyewitnesses to their legendary exploits on the baseball field, introduced me to these men and their excellent athletic accomplishments.

One of my all-time favorite bedtime stories is the legend of Cool Papa Bell, who was so fast that he could turn off the light switch on the wall and be in bed before the room went dark.

And then there were the scoffers who told me the story was pure myth. Others stated that the light switch was delayed, allowing Bell to pull off his legendary feat. Many were the same people who pooh-poohed Harry Houdini’s exploits. As a child with an active imagination, I believed in the legend.

But there was one fact in my mind that could not be ignored or dismissed — that there was a Negro League’s baseball organization and that the legendary stars of that league were real human beings, standout Black men.

Critics of many commentaries on this subject usually bring up that “there were no true statistical facts (numbers)” to quantify these historical opinions. But thanks to the diligent work of Negro League historians like Frank Jordan, whose father played in the ‘B’ division of the Negro Leagues, and John Thorn, chairman of the Negro Leagues Statistical Review Committee tasked with reviewing thousands of box scores and other data and information as part of Major League Baseball’s fact-finding mission, enough accurate statistical data have been brought to light on this subject.

On May 30, 2024, Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred made the official announcement that the statistics of more than 2,300 Negro League players from the years 1920-1948 were officially incorporated into MLB’s historical record, and that the records will become a permanent part of baseball history.

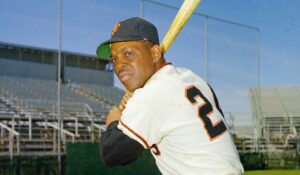

For people like Sean Gibson, the great-grandson of the baseball Hall-of-Famer Josh Gibson, and part of the 17-member Negro Leagues Statistical Review Committee, it was a day too long awaited. The same could be said of people like Rose and Lydia Teasley, daughters of 97-year-old Ron “Schoolboy” Teasley, one of only three living Negro Leaguers (93-year-old Willie Mays and 99-year-old Bill Greason being the others); Joyce Stearnes Thompson, one of the daughters (Rosilyn Stearnes-Brown being the other) of Norman “Turkey” Stearnes, posthumously inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2000; and all the way to people like Frank Jordan. Jordan put these words to this historical achievement: “I have worked many years of my adult life to see this day. Sometimes, a journey takes a long time to reach a truthful and justified destination. Was the wait worth it? I would put a definite YES to that statement.”

Thorn, the committee chair, described the MLB decision as “not only righting a social, cultural, and historical wrong, it’s defining baseball as a game for Americans, without exclusion.”

He said, “Baseball is a game of consistency and change. We may be slow to change, but when we do, it can be profound.”

When word reached Sean Gibson, he said, “Oh my God. I had to hold this in. I couldn’t tell nobody.”

The overwhelming part of this story is that the name of Josh Gibson is now at the top of the list for Major League Baseball’s career batting average (.372, five points higher than Ty Cobb’s .367), slugging percentage (.718) and OPS (1.177), and the single-season leader in batting average (.466) and slugging percentage (.974). He arguably has the statistical basis to be mentioned as the greatest hitter of all time.

Gibson’s other achievement, mythologized in baseball history — his plaque in Cooperstown, New York says he “hit almost 800 home runs” — will still be omitted from the league statistics, but the home runs and RBI’s (runs batted in) and countless other stats Black players put up more than 100 years ago will now appear next to those of modern-day icons. The fight will have to continue over Gibson’s official home run total.

In the meantime, Gibson’s great-grandson will continue his battle to get every statistic of his legendary ancestor on the record. Young Sean Gibson has also lobbied for the past few years to rename the Baseball Writers’ Association of America’s Most Valuable Player Awards, previously named after Kenesaw Mountain Landis, MLB’s pre-integration commissioner, after Josh Gibson.

“How ironic would it be for someone like Josh Gibson to replace the person who denied him and other great Negro league ballplayers an opportunity to play Major League Baseball,” said Sean Gibson in a recent interview in USA Today. “It’s poetic justice.”

The release of MLB’s newly integrated statistical database comes one week after Major League Baseball and the MLBPA (Major League Baseball Players Association) announced an annual retirement benefit for living players, and three weeks before the San Francisco Giants and St. Louis Cardinals play June 20 at historic Rickwood Field, MLB’s first regular-season game at the former home of the Negro Leagues’ Birmingham Black Barons.

Those involved with the Negro Leagues Family Alliance want the celebration of the Negro League’s history to continue beyond next month. They have advocated establishing May 2 as Negro Leagues Day across baseball each year. Teams would mark the anniversary of the first Negro National League game, May 2, 1920, with old-time jerseys and caps and Negro-League-themed giveaways.

“It’d be an emotional day,” Ron Teasley said last year.

There are voices of discontent from specific segments of white and Black communities over this issue. Some white people feel that what happened in the past should be left in the past, and that the recognition of the Negro League was fine just the way it was — before May 30, 2024 — a day of truth and reckoning for the 2,300 Black men who were denied their place in baseball history for far too long.

While some Black people applaud MLB for “coming to light” on this sensitive issue, others feel that much more needs to be done to rectify this grave injustice for a group of men who gave so much to the game of baseball while receiving so little in salaries, recognition and respect for their efforts.