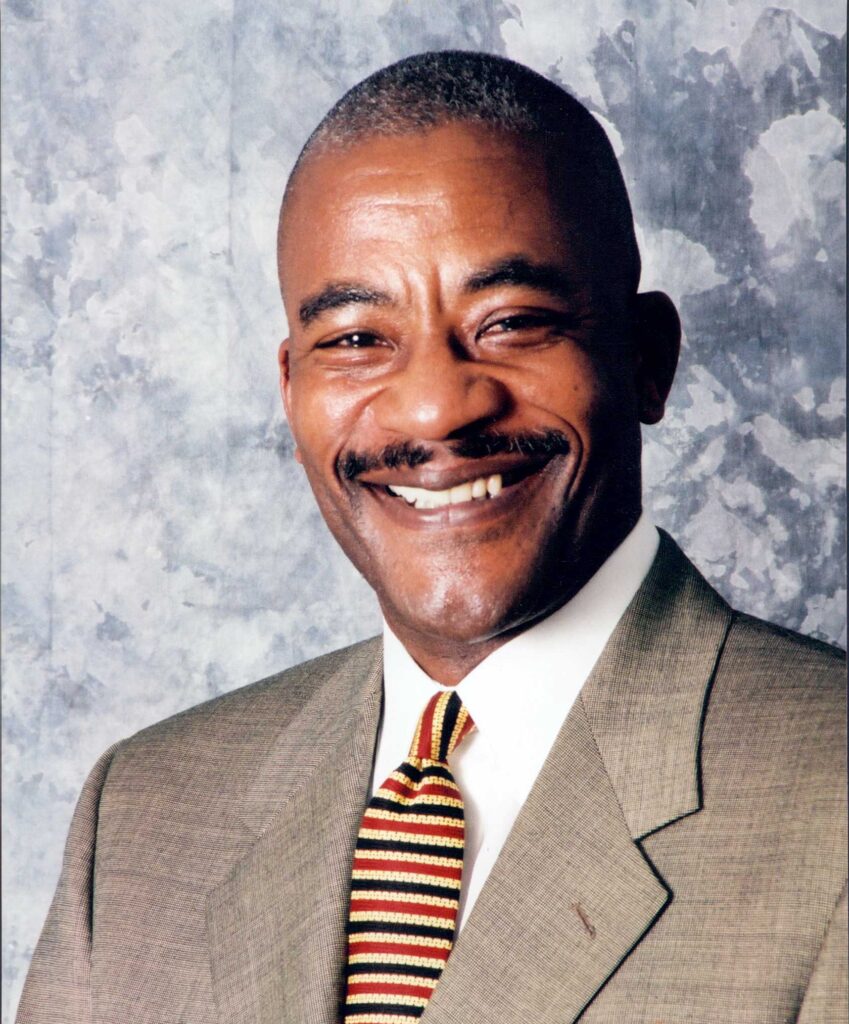

Vietnam vet Ernest Washington reflects on life before, during and after service

‘We should always remember’

Every decision Ernest Washington Jr. has made since 1968 has been informed in part by his time serving in the Vietnam War, the 20-year conflict between the country’s northern and southern factions.

“I look back at that situation every time I have some difficulty now, because the ultimate answer all the time is it’s not as bad as it feels. It’s not as bad as the bush,” he said. “Make a decision, just like you had to do there.”

Washington is 76 years old now, but his time in the field is cemented firmly in his mind.

“Nine months, 29 days, 11 hours and 15 minutes,” he said, recalling exactly how long he spent in the Southeast Asian country as one of 300,000 African Americans to serve in that war, according to the Library of Congress.

Highlighting the experiences of African American veterans such as his is important, he said, because “the majority of our children and majority of people of color don’t know that story.”

Washington’s story began in Lower Roxbury in a diverse neighborhood inhabited by Black, Jewish and Italian families. In 1966, at 18, Washington received a letter drafting him to military service, and his mother attempted to stop her son’s conscription to no avail. His family ultimately showed their support.

“Go do the work son, and come back home,” Washington recalled his father saying.

Soon after, Washington and his two best friends, who also had been drafted, headed to Parris Island, South Carolina, where they began boot camp training. Having familiar faces nearby was “a big help,” he said.

He and his friends were together until duty was chosen. Washington and one of his pals were assigned to the United States Marine Corps First Marines, he said, stationed in military bases in the coastal city Da Nang, before moving to Con Thien, a combat base further north near the demilitarized zone. There, he spent his days executing deadly search-and-destroy missions.

Camaraderie was essential in battle.

“Watching the back is one thing,” he said, “but watching the back [in Vietnam] encompassed everything if you wanted to go back home, and all of us complied.”

While aiming for survival, Washington faced complicated feelings as he served. For example, at one point, he realized that he was killing “another colored man,” the same dilemma his older relatives faced while serving in Korea. This realization, Washington said, shifted his outlook on the war.

“It’s not that I was any more lenient,” he recalled. “If I had a chance, any kind of opportunity that was different than just taking orders and killing, I tried to fall in the middle of that.” All the men in his unit adopted a similar mindset, he said, but sometimes “you didn’t have any choice.”

This was especially hard for him to contend with, particularly given the disproportionate conscription of Black men in the war. While African Americans comprised about 12 percent of the U.S. population at the time, they accounted for a third of ground combatants in the war, according to the Library of Congress. African Americans also experienced the highest casualty rates, which Washington said “put a hurting on Black people.”

Washington witnessed immense horrors and even suffered a gunshot to his left shoulder that saw him extracted from the zone by helicopter. America sent him to do a job, he said, but “I don’t think even they knew what the add-ons were going to be in terms of actually being in Vietnam.”

His best friend died in action.

As is the case for many veterans, specific parts of his military service have stuck with him. One of them is April 4, 1968 — the day he returned to the U.S.

“Just kind of thing you will never forget,” he said.

His return created a mix of emotions. Upon his arrival, he was met with anti-war protestors, some of whom spit on him, but he also felt “the happiness involved in surviving.”

He decided he would do the best he could with the rest of his life.

To heal the wounds of service, he said, he leaned on services provided by the Veterans Administration and Veterans Benefits Clearinghouse, a nonprofit organization that assists veterans in reintegrating into civilian life post-service.

As some of his veteran peers joined the Black Panther Party, Washington decided to continue his education, attending Bentley University and Northeastern University for undergraduate and graduate school, respectively.

“I went and did the work, came back home and kept working,” he said.

In 1986, Washington established Vanguard Parking & General Services Corporation, a business that operates Northeastern University’s parking garages and provides dormitory cleaning services. Through his business, he created an employment program that recruits locally and trains people from his neighborhood and beyond.

It’s been five decades since he returned from service, and Washington said he has healed “a great deal” from the sores of the war. Processing his military service was challenging, he said, but he’s glad he went through it.

“Concealed, reconciled, forgiven,” he said of his perspective on the war, adding that community support was instrumental in getting him to where he is today.

“Conscientious, caring and active as a representative of the military experience,” is how Bruce Bickerstaff described Washington. Bickerstaff, also 76, was born in Pittsburgh and raised in Ohio. He served in Vietnam from 1967 to 1971 and moved to Boston thereafter.

Bickerstaff met Washington through veterans activities, including Concerned Black Men of Massachusetts, of which Washington is a founding member.

When Bickerstaff volunteered for military service, he said, he was “naive” about the “malaise” of military service. Like Washington, Bickerstaff dealt with an added layer of contention.

“As a Black man … the first sense was representing our community in defense of the country,” he said, “but then realizing that the motivation of the military had nothing to do with the protection of this country. It was a power move, if you will.”

When he returned to the U.S., Bickerstaff once again grappled with feelings of confusion. The promise of economic and social change did not materialize, he said, and many Vietnam veterans didn’t receive the recognition they deserved because many viewed it as an “unjust war.”

The rhetoric around the war has since shifted, with many now being thanked for their service, Bickerstaff said, adding that “the legacy of the Black Veteran” beginning with the Revolutionary War should be better known.

Washington has spent time raising awareness about the experience of African Americans in war, teaching a Zoom course at Northeastern University about the subject. When he retires soon, he will have time to finish the book he said he’s been writing for two decades about his life story and time in Vietnam.

“We should always remember,” Washington said. “For me, the ones I remember, I remember every day; it’s not just Memorial Day.”