As another Memorial Day passes, we gather with family and friends to honor those who gave their lives standing up for our country. Black Americans have a distinguished place in the ranks of the fallen, because our sacrifices often occurred during points in history when the ideals we fought for abroad were denied to us here at home.

Nevertheless, we have always honored our military and taken pride in our contributions to America’s claim as “the land of the free and the home of the brave.” We have taken our struggles to the streets and to the courts and to the battlefields of every war to protect and redeem the promise of America to secure our inalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. As we have continued our fight against social and legal injustice and inequity, we have also continued to serve honorably in the armed forces.

Just a few months ago, Army Sgt. Kennedy Sanders from Waycross, Georgia, was laid to rest after an Iran-backed militia launched a lethal drone strike against a U.S. military outpost in Jordan. She was just 24 and had been deployed as part of an effort going back to 2014 to combat the Islamic State in the region. President Biden, who had flown to Dover Air Force Base to honor Sanders and two other soldiers as their remains were brought home, posthumously promoted the young Black servicewoman from specialist to sergeant and awarded her the Purple Heart. Taps were played by an Army bugler as her flag-draped coffin, taken from a horse-drawn carriage, was lowered into a grave at her hometown Oakland Cemetery. An officer in dress blues knelt before her parents to present the folded flag and offer the thanks of a grateful nation.

Her service and sacrifice are anything but an outlier for Black Americans.

Before American independence was even declared, people of African descent were active in the cause of liberty. Crispus Attucks, a Black sailor from Framingham, died in a hail of British musket fire in the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770. The death of Attucks and four others occurred during a protest in front of the seat of British power in the Massachusetts colony. Their sacrifice radicalized the populace and led to open rebellion by 1775. Author William Cooper Nell, who chronicled Attucks’ death in a book entitled, “The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution,” proposed that his death was the first in the march to liberty of this country. It was publisher William Monroe Trotter of the Boston Guardian who pushed for March 5 to be named Crispus Attucks Day.

Black patriots like Peter Salem fought the British in Concord in the American Revolution’s opening volleys, and Salem was one of the heroes of the Battle of Bunker Hill. It was General George Washington himself who early in the war reversed an earlier prohibition on the enlistment of Blacks in the forces under his command. An estimated 9,000 served in various capacities during the conflict.

But when it came time to organize the government of the newly independent republic, African Americans were denied full rights as citizens by a flawed Constitution. That did not stop Blacks from serving in various military campaigns — from the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War through frontier battles to expand westward settlements — right up to the Civil War. Before a naval battle in the War of 1812, a commodore was asked if his Black sailors would flee before hostile British fire. “No, sir,” he answered. “They don’t know how to run. They will die by their guns first.”

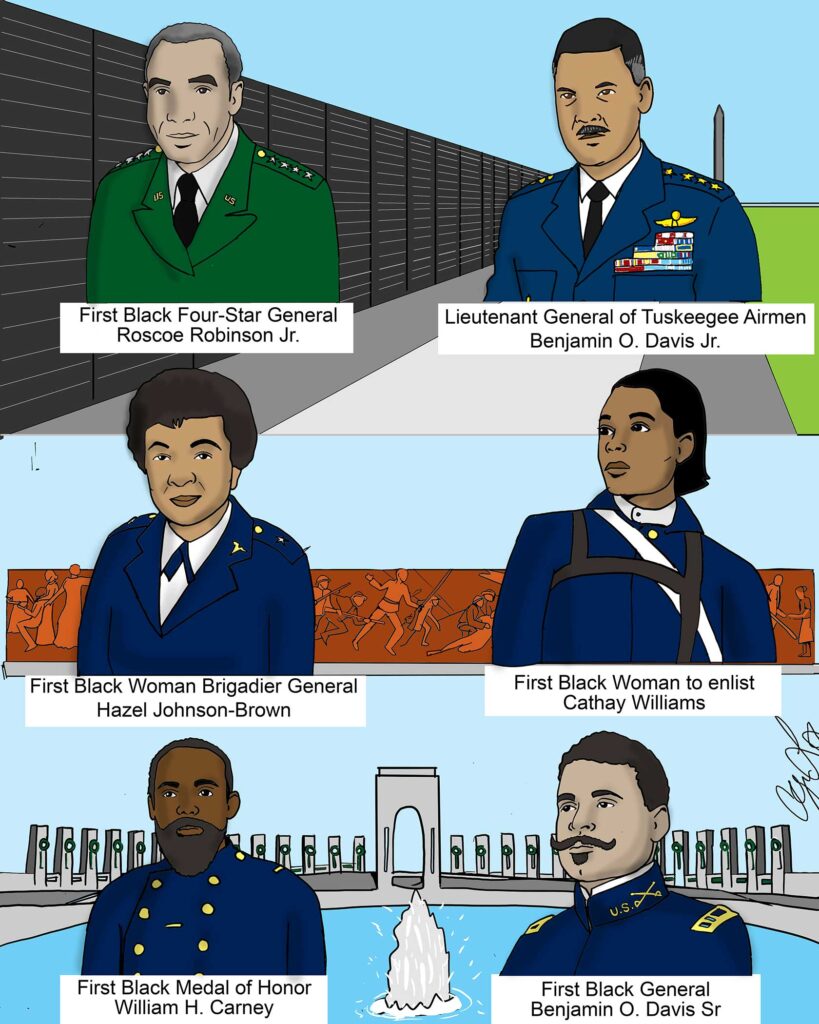

During the Civil War, close to 200,000 Black troops, including more than 7,000 officers, wore the uniform of the Union Army in 163 units. The first was, of course, the famed 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, who marched off to glory at Fort Wagner, South Carolina, to once and for all settle any doubt about the patriotism and fighting ability of Black soldiers.

Regiments of “Buffalo Soldiers” were master horsemen, scouts and cavalry fighters in the Indian wars and also formed an integral part of Col. Teddy Roosevelt’s charge up San Juan Hill during the Spanish-American War. Five Black soldiers received the Medal of Honor for their part in the battle.

Units like the “Harlem Hellfighters” from New York’s 369th Infantry Regiment fought with distinction, serving under French army command in World War I, but returned to face a rising backlash against demands from the NAACP for equal rights and federal protections from lynching.

Segregation in the military continued through World War II. An estimated 125,000 Blacks served overseas in the armed forces. The all-Black Tuskegee Airmen won accolades for their aerial skill, while segregated infantry, artillery and tank units fought bravely on the ground. Returning soldiers with combat decorations, like future U.S. Senator Edward Brooke, who served as an officer in Italy, were key leaders in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

Bowing to pressure, President Harry Truman finally ordered the full desegregation of the military in 1948. Over 600,000 African Americans served in the Korean War — the first military campaign with integrated forces — and 5,000 died in combat.

During the Vietnam War, Black troops served disproportionately in combat roles and suffered higher casualty rates. While they fought abroad, protests raged at home. Emerging from battlefield experience in the Southeast Asian conflict, Colin Powell rose to become the first Black chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He would go on to play a key role as Secretary of State in the U.S. wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, stages in the “War on Terror” that continue to involve hundreds of thousands of Black men and women serving in uniform around the world.

Everyone should remember and honor the soldiers, sailors and airmen who gave their lives to protect our way of life and defend the grand experiment of our founding fathers. We in the African American community have a special obligation to those who have given their last full measure of devotion in defense of American ideals. That’s because the sacrifice often came in spite of being denied the full rights and privileges of those ideals. Our brothers and sisters fought and died for the hope, rather than the reality, of full equality — and for that, we are eternally grateful and eternally committed to making sure their sacrifice was not in vain.