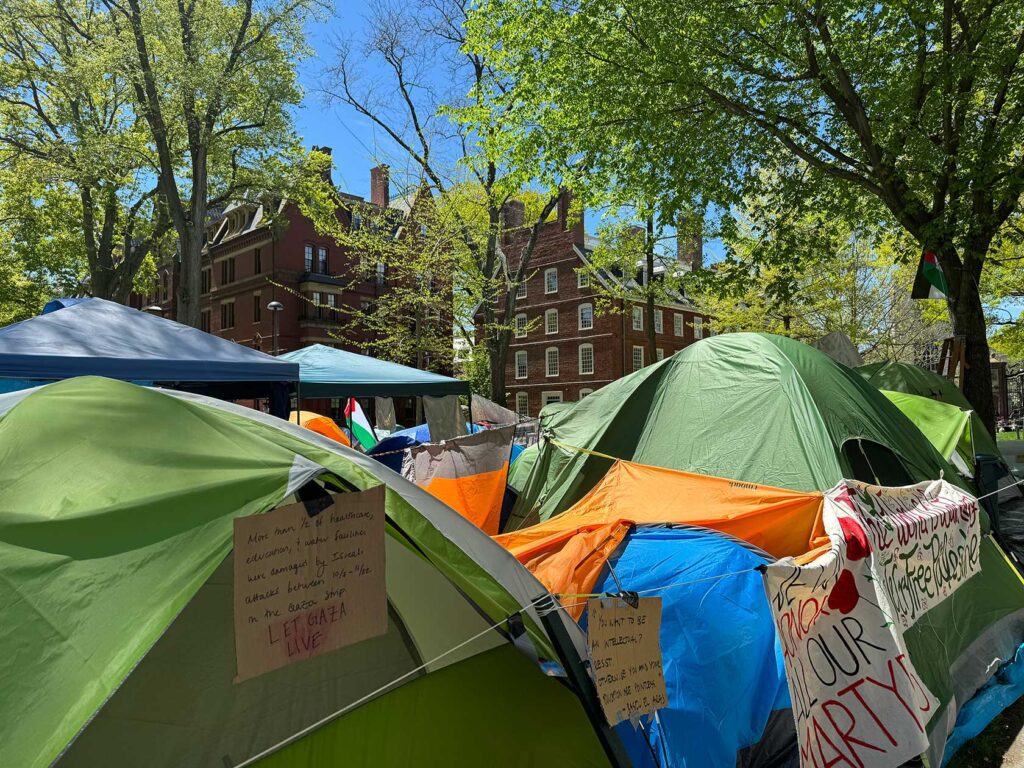

When students at Harvard voluntarily dismantled their encampment last week, it marked the end of a month of protests across the Greater Boston area as students across the region voiced their opposition to university investments in companies with ties to Israel as the country continues its war in Gaza.

The encampment came down, after nearly three weeks, after university officials agreed to a meeting between protesters and Harvard’s governing boards about the university’s endowment and investments related to Israel, as well as the reinstatement of 22 students who were placed on involuntary leaves of absence due to their involvement in the protests.

In doing so, Harvard became one of at least eight colleges and universities across the United States that agreed to disclose, divest or discuss divestment in response to the student protests.

Across the Boston area, other protests ended more abruptly, with police intervention and student arrests.

The protest at Harvard saw support from the campus’s African American Resistance Organization. Prince Williams, one of the co-founders of the group that’s also known as AFRO, served as an organizer with Harvard Out of Occupied Palestine, the coalition that set up the encampment.

Williams said he sees parallels between how Israel treats Palestinians in Gaza — calling the system an apartheid — and how Black communities in the United States have been treated.

“That history of Black people in the United States has been a legacy of segregation, Jim Crow, American apartheid,” Williams said. “That legacy of shared oppressions continues to unite us in solidarity with one another on a global level, across the diasporas, Black and Palestinian.”

AFRO in particular was organized at the start of the 2023-24 academic school year — around the time student activism around the treatment of Palestinians in light of the war in Gaza began — and has been engaged in the topic since.

Williams pointed to the groups activism around Palestinian issues as a part of a legacy of Black civil rights leaders, like Jesse Jackson, Nelson Mandela and members of the Black Panther Party pushing for change in the region.

“We see ourselves as the continuation of a tradition of Black people who understood that there is no Black liberation without Palestinian liberation,” Williams said.

Neither the pro-Palestine protestors nor local Jewish groups view the end of the encampments as the end of activism around the issues.

Williams said the deal that led to the end of the encampment, with its promises to discuss divestment and recommendations to expedite decisions on student disciplinary proceedings, as victories for Harvard Out of Occupied Palestine, also called HOOP, but said they are not substantial gains, calling the shuttering of the encampment a moment to regroup and think about other ways to push for their demands.

“With these encampments winding down, I don’t perceive this as an end or a period of lull but actually a beginning to something much bigger,” Williams said.

In an Instagram post announcing the end of the encampment, Harvard Out of Occupied Palestine said the agreement did not include a solid win around movement toward divestment.

“These side-deals are intended to pacify us away from full disclosure and divestment,” the statement alleged.

Meanwhile, Jeremey Burton, CEO of the Jewish Community Relations Council of Greater Boston, said he views the shuttering of the encampments as being as much a part of the end of the academic year as anything else.

“It’s not going away just because colleges students have gone home for the summer,” he said.

Even following the deal, protests continued. On Sunday, a HOOP protest drew 2000 attendees after Harvard suspended five students and placed more than 20 on academic probation, a move that will keep 12 seniors from graduating at the university’s commencement Thursday.

HOOP, in an Instagram, called the move by the university a violation of the agreement with the student protesters that led to the dismantling of the encampment.

According to reporting by the Harvard Crimson, when the end of the encampment was announced, the university was set to encourage schools within the university to begin processing petitions for reinstatement from involuntary leave and agreed to expedite the proceedings for more than 60 students facing disciplinary charges with “precedents of leniency for similar actions in the past.”

Following Sunday’s protest, in a statement to the Crimson, a university spokesperson said the agreement never made promises about the outcome of the disciplinary proceedings, only to move forward with them expeditiously.

The shuttering of that last encampment comes even as others push for continued action around the war, including calls for a ceasefire, most recently from the Boston City Council. When the City Council passed the resolution in an 11 to 2 vote, Boston joined others — including Cambridge, Somerville and Medford — and became the ninth municipality in the state to pass a similar resolution.

As municipalities and organizations continue to make statements, Burton called for a clearer distinction between protests against the war and protests against Israel as a country, as well as increased understanding of what some of the saying and symbols pro-Palestinian protesters are using and the impact they have on Jewish communities.

“What I’m hoping for is that local leaders will continue to more clearly speak out, to make the distinction between criticism of how a government prosecutes a war and criticism of the existence of the State of Israel,” he said.