Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery

Lucilda Dassardo-Cooper in conversation with artist Reginald L. Jackson

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/RLJ3-798x1024.jpg)

View Banner Art Gallery

Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery

Sponsored by City of Boston | Mayor Michelle Wu

This is the 21st interview in a weekly series presenting highlights of conversations between leading Black visual artists in New England. In this week’s installment, artist Lucilda Dassardo-Cooper talks to artist Reginald L. Jackson. The interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

A native of Springfield, Massachusetts, Reginald L. Jackson is a professor and visual artist. He received his AAS in graphic arts, printing and photography from the Rochester Institute of Technology and his BFA and MFA in graphic design, film and photography from Yale University.

Jackson also earned a MSW in policy and planning from SUNY Stony Brook University and a Ph.D. in communications and visual anthropology from the Union Institute. He is the recipient of numerous academic awards, including a Fulbright Fellowship and fellowships from the Ford Foundation, the Smithsonian Institute, UMass Boston, and MIT. Jackson has documented African retentions in Ghana, Nigeria, Brazil and Cuba. His work can be found in the permanent collection of the MIT Museum, the RISD Museum of Art and the Boston Athenaeum, among other places.

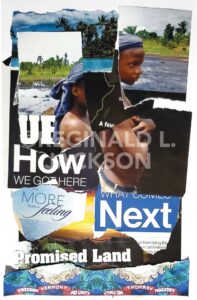

“Martin Freeman collage,” A Peculiar Freedom Series 2024 by Reginald L. Jackson. PHOTO: Courtesy of the artist

Lucilda Dassardo-Cooper: What fascinates you about documenting through your photography the lives, happenings and experiences of others?

Reginald L. Jackson: I come out of the understanding that when you have the tools, particularly in the arts, you need content, and that content you need to be informed about. So, I began to think more in terms of the social dynamics behind what I was doing as a documentarian. I’m much more comfortable documenting what’s going on, because … it gives me the opportunity to learn as well as to record what’s going on around me. That’s linked with community service, which is something I’ve always tried to keep in the forefront. We are here for a particular reason, and if you’re part of the community, you want to be able to contribute in a meaningful way.

The photography and films you’ve created over the years have not only included Africa, but other countries. Tell us about some of the other countries.

Primarily during the late ’70s and into the ’80s, I spent a lot of time in Brazil. When I heard about the 100 million or so people of African descent in Brazil, I said, I’ve got to go there and check this out. I went down there and got hooked on Brazil, particularly Bahia and Salvador. I had been to Festac, which is a festival of arts and culture that happens every once in a while. There hasn’t been one in quite a while, but I had seen the Yoruba tradition at work in Nigeria, and when I went to Brazil, I saw the same thing going on and I began to work on a documentary, which was a part of my dissertation in communication and visual anthropology.

And you were a professor at Simmons.

Yes. I came to Simmons in 1974 to set up the photo communications program.

There was none before you came?

Right. In fact, I neglected to ask about the darkroom when I came for an interview. It turned out that it was under a stairwell in the main building, so I had to build all of that. I spent 21 years there, and eventually went to Africa on a Fulbright. I studied the resistance communities in northern Ghana. When slave raiders came from the north to collect Africans, people didn’t say, “Okay. I’ll go. I want to go to America.” It was a very sad situation, horrific. People were captured, but people resisted. They built walls around the cities. They hid in caves — the women, children and elders. So, there’s this whole legacy that we don’t hear about. We hear these stories about the slave trade, particularly the middle passage, that are horrific, but they’re all kind of one-sided and we don’t really get to know what was going on.

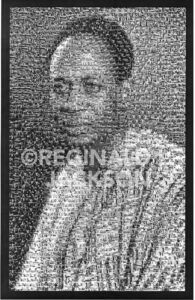

“Kwame Nkrumah Series, Ghana” (black and white montage) by Reginald L. Jackson. PHOTO: Courtesy of the artist

Later in 2007, I was invited back along with my wife to be a part of the founding of a new university, African University College of Communications in Accra. I spent five years in Ghana, living and working there and founding this university, which is running very nicely now, I’m proud to say. We’re really pleased about having had that opportunity.

We’d like to hear about your current projects and future endeavors.

I’m working on a project called “Peculiar Freedom,” which has to do with free Blacks in New England from 1750 to 1860. I’m working with a filmmaker in Vermont. Her family arrived here from Barbados to New Hampshire and then eventually Vermont. … We’re working on a project that’s going to illuminate the lives of five free Blacks in New England. When we hear about New England, we think lily-whites, especially Vermont, Maine and New Hampshire to some extent. We’re pitching that now. We’ve been able to get an NEH grant to do the planning. Now we’re doing the proof-of-concept piece to get the production money, so hopefully this time next year, we’ll be in production.

View Banner Art Gallery