Can churches help narrow the wealth gap?

Three teams of community organizers and students explored that question during a daylong hackathon on the racial wealth gap. The organizer, Karilyn Crockett, a professor of urban history, public policy and planning at MIT, has said “there’s no bigger challenge.” The teams focused on white suburban churches with financial and other resources, a word that popped up often in discussions.

The hackers taking on the social problem, instead of a technical one, tapped archival material to guide their deliberations on possible initiatives. Two teams concluded white churches in Massachusetts have in the past contributed to addressing the racial wealth gap, but these days many resist going beyond the charitable donations they already make to help needy individuals and joining activist coalitions.

“They always say, ‘We donate. We donate,’” said Elsy Almeida, a supervisor at the Roxbury Youth Programs of the Unitarian Universalist Urban Ministry in Roxbury.

Ivette Melendez, the community organizing and engagement coordinator at METCO, indicated she is less than optimistic about building fuller relationships between white suburban congregations and Black community organizers.

“Not to say the white community is the savior, but they have the resources,” Melendez said.

Later, she lamented that Unitarian Universalist Urban Ministry leaders say they do continuous outreach but “the issue that they are coming across is the white community churches aren’t attracted to coming into Boston. No matter how much invite they execute and offer, there’s no relationship-building amongst them.”

During the hackathon on May 4 at MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning, three faith-related teams explored how to build new social movements and coalitions for cities and suburbs to share wealth, with a focus on education.

Participants in a racial wealth gap hackathon gather in a MIT lounge for the closing session on May 4, surrounded by walls covered with archival documents on the struggle for racial justice in Boston. PHOTO: KENNETH J. COOPER

A year ago, a similar hackathon on housing at the same venue suggested ways suburban churches, particularly Unitarian ones, could help increase Black wealth. Recommendations included such congregations spending more with businesses owned by people of color, reassessing how their endowments are invested, advocating additional affordable housing “in their own suburbs” and raising funds to support low- or no-interest loans to buy homes in Roxbury.

This year, one team partnered with the Unitarian Universalist Urban Ministry, which is affiliated with 40 of the denomination’s churches in the state. That team noted that in 1968 the church established a Black Affairs Council, a nonprofit affiliate that engaged in community organizing and economic development.

“Basically, they received money from Unitarian Universalist churches to advance racial justice and civil rights for Black people in the United States, and they supported both vocational and educational work,” the team reported.

Those hackers proposed a scholarship and mentoring program for high school juniors or seniors of color because “college is crucial to increasing earning potential,” with only 24% of Black adults over 25 holding a degree. Twenty members of congregations would serve as mentors, and another 80 would donate to the scholarship fund.

Members of a team partnered with the Massachusetts Council of Churches do research on their devices during the racial wealth gap hackathon. PHOTO: KENNETH J. COOPER

Another team’s partner was the Massachusetts Council of Churches, which represents 18 denominations, including AME, AME Zion, Unitarian, Episcopalian and United Methodist, according to the council’s website.

That team found that, also in 1968, the council supported the national Poor People’s Campaign that culminated in a march on Washington, built 2,700 units of affordable housing and contributed $60,000 to fund summer jobs, working with the Boston Urban Coalition. That sum is equivalent to more than a half million dollars today.

Melendez concluded the council’s efforts back then “absolutely” had an impact. The team was one of six finalists for the hackathon’s monetary prizes.

A third team was associated with the Episcopal City Mission in downtown Boston. Rev. Edwin Johnson, a priest who is director of organizing, said in an interview that the mission engages with 80 Episcopalian churches from Martha’s Vineyard to the Berkshires out of 252 congregations statewide.

But the team described only 15 as “very receptive congregations” that are involved in making grants to “justice-oriented nonprofits” with a focus on reparations, lobbying for state legislation and “solidarity economy investing.”

Among the proposals hackers on the Episcopal team developed was a “cross race” team of paid interns to speak at Sunday services and lead an interracial youth summit to promote awareness of the racial wealth gap and issue calls to action.

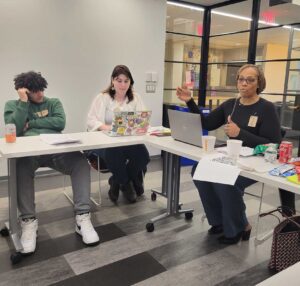

Vonnessa Goode-Knight, executive director of Project Hope Boston Inc. in Roxbury, makes a point to her team at the racial wealth gap hackathon at MIT on May 4. PHOTO: KENNETH J. COOPER

One other team, with METCO as a partner, shared with the faith-related ones the “hack track” of building urban-suburban coalitions to promote wealth sharing.

Those hackers proposed a community fair in 2026 tied to the integration program’s 60th anniversary. The fair, to be held in four regions covering the 33 suburban districts that educate Black and Latino students from Boston, would provide anti-racist and anti-bias training in addition to cultural performances and fun activities.

The METCO team won the hackathon’s first-place prize of $1,000. There were a dozen teams in all. They were multi-racial and intergenerational and occupied every classroom in MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning.

Jean McGuire, the retired longtime director of METCO, spoke to the hackathon, which saw about 140 people register to participate on a spring Saturday.

“Anything that gets people together to exchange points of view, experiences — that’s good for us in a democracy,” she said in an interview.

Asked how to solve the racial wealth gap, McGuire said, “That’s a matter of who controls the resource,” citing banks as an example.

Crockett, the MIT professor who has organized both hackathons, noted that the small teams working around classroom tables “flatten” ordinary hierarchies. She pointed to a 13-year-old student from Boston College High School who emerged as the energetic leader of a team whose members included someone with a doctorate in education.

Crockett is involved with what she described as a separate but related effort to update and expand the 2015 “Color of Wealth” report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, which found a gaping disparity in the assets of Black and white residents of Boston.

“It can’t just be corporate folks, banks and businesses,” she said. “From a solutions perspective, I don’t want to leave it up to the economists” and leave out organizers, activists, young people and nonprofit directors.

One approach to closing the racial wealth gap, Crockett said, is to have people with resources put some of them in service of communities of color.

The hackathons have been supported by a grant from Trinity Church Wall Street in New York City, whose endowment usually supports seminaries. Crockett said MIT is the only current grantee that is not one.

The final hackathon, she said, will be next year and focus on jobs and entrepreneurship.