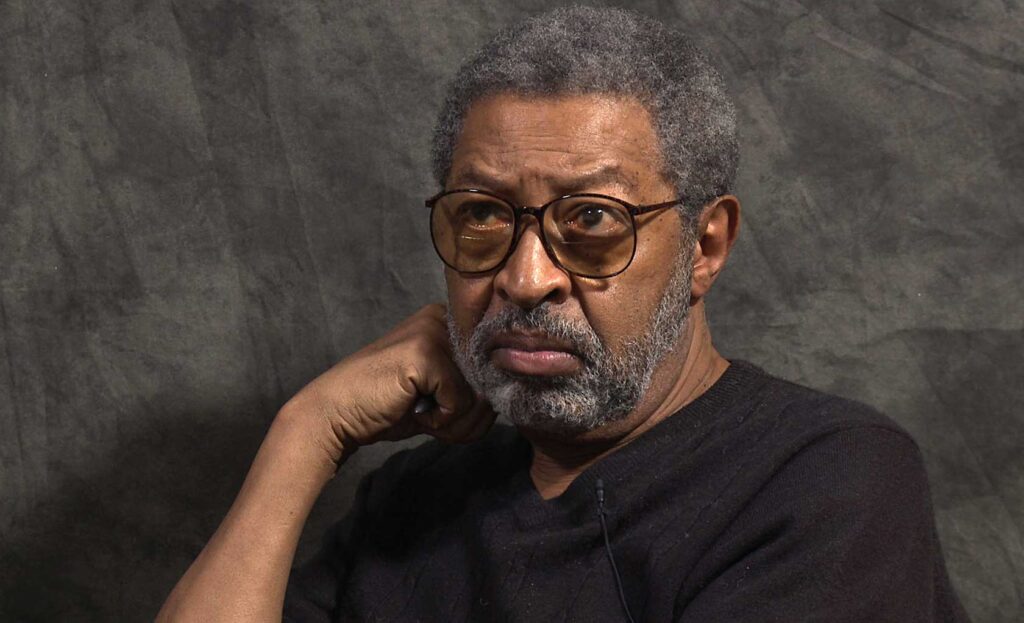

Bill Strickland: A long life of teaching, inspiring and activism

Civil rights champion, scholar, 87

In a life dedicated to teaching, writing and organizing as a behind-the-scenes political strategist, Bill Strickland had an outsized presence that belied his soft-spoken, even-tempered nature.

There is, however, one stop in his voluminous resume, full of nods to progressive causes, that may puzzle those who only knew him as a 40-year professor of Afro-American Studies at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst — that of U.S. Marine.

As a voluntary enlistee of that elite arm of Western power from 1956 to 1959, Strickland, who saw the military as a Southern province, was even then keenly observing his environment.

“What they teach you is, when you think you cannot run another step, you can run four or five miles,’’ he said of his three years in the service in a 2011 interview with the Civil Rights History Project.

“You’ve been acquainted with personal reserves you never knew you had,” he added. “That can create a certain image that can also work against you, because you can start to believe you are invulnerable. But for some of the guys, the Marines was like the only mother and father they had, and trying to understand where those needs came from was educational to me.’’

It was typical of Strickland that he found empathy even toward those whose world view he decidedly didn’t share.

William Lamar Strickland, 87, died April 10 at his home in Amherst where he taught at the respected W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies.

A graduate of Boston Latin School and Harvard University, a native Bostonian and son of Roxbury, Strickland made his presence felt locally and internationally as a friend of Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael, among other luminaries, and as a close advisor to Jesse Jackson during his presidential runs several decades ago. Strickland retired from teaching at UMass in 2013 after 40 years.

He was raised by his mother, Mittie Louise Strickland (Norman). His father perished in World War II, he said, but he was surrounded by several aunts and other relatives who helped raise him.

He graduated from Boys Latin, since renamed Boston Latin, in 1954. Two years later, he enrolled at Harvard College after seriously considering Howard University — but upon visiting, he said, it became a risky proposition to enroll there because the school’s population of females was top-heavy with 8s, 9s and 10s on the glamour scale, he recalled, perhaps making academics an afterthought.

His knowledge of the African revolutionary movements gaining traction in the middle of the previous century was comprehensive. He personally knew many of the leaders and the unique struggles they faced, whether in Anglophone, Francophone or Lusophone Africa.

His associations with political groups and the sources he wrote for were voluminous. But perhaps his biggest contributions came in the classrooms of the New Africa House, a former dormitory once known as Mills House, that in the 1970s became the hub of activity for the majority of Black students for several decades.

The building, open to everyone, nonetheless served Black students through the Committee for the Collegiate Education of Black Students, with academic advisors, career counseling and the emotional support young people away from home for the first time would need.

The fulcrum, though, was the academic goings-on. The “Afro-Am” department had to be among the largest and most comprehensive in the country, with up to nine tenured professors and adjuncts on staff.

Manuel “Rick” Townes, who finished undergraduate work in 1974 and then went on to serve at UMass for 26 years in various capacities, said Strickland was one of the stars of the highly regarded department, his knowledge and teaching reaching across all areas of study.

“I think Professor Strickland was the political guy, and his overlay of politics permeated those other disciplines,’’ said Townes.

“He had a sense of humor and a dry wit about him and a kind of sarcastic humor,’’ added Townes. “He was a funny guy. He’s the kind of guy where, if you are in a room full of people and Bill Strickland walks in, the attention calmly shifts from whatever was happening to ‘Strick’s here and he is going to light up the room.’”

After serving stints in London and Vietnam during his enlistment in the Marines, Strickland returned to Harvard to finish his undergraduate studies. He joined the Northern Student Movement and rekindled a friendship with Malcolm X while moving away from the civil rights model of protest in the early 1960s towards the Black Power Movement.

He became a founding member of Malcolm X’s Organization of Afro-American Unity in 1964 as a student representative and went South to assist the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party’s challenge, led by Fannie Lou Hamer, to the Democratic National Convention.

Strickland’s first academic post was at Columbia University, where he served as a lecturer starting in 1966. He later moved to Atlanta to co-found the Institute of the Black World, the nation’s first Black academic think tank. He joined the UMass faculty in 1973.

While he fathered no children, he did have a longtime love interest, Cynthia Perkins, according to Townes. Strickland also had a flat on the Spanish resort island Ibiza, where he spent a lot of Mediterranean time in retirement.

“I’d see him in rooms sitting among people like James Baldwin, Chinua Achebe, Shirley Graham Du Bois and others and be amazed how everyone in the room would draw off his knowledge. When they’d sit around, all of those people would draw from Strickland’s political acuity to help them navigate the moment,” said Townes.