Orenthal James Simpson, the hall-of-fame running back and pitchman supreme whose acquittal on charges of double-murder proved a racial Rorschach test on perceptions of justice and police misconduct in America, died April 10 of prostate cancer at his home in Las Vegas.

While views of the superstar celebrity’s guilt or innocence in the deaths of his ex-wife and her boyfriend left the nation deeply divided along the color line, the case itself unified the country as a vast viewing audience collectively glued to the television through every step of the social and legal drama.

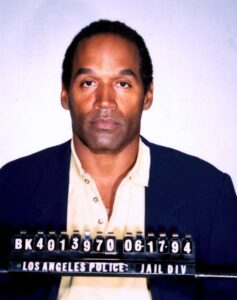

After the lifeless bodies of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman were discovered outside her Los Angeles condo on June 13, 1994, Americans watched, captivated, as Simpson fled police on a low-speed twilight chase along the freeways and back streets of Los Angeles, his friend Al Cowlings at the wheel of his white Ford Bronco as he crouched in the back seat of the two-door vehicle, holding a gun to his head.

News copters flying overhead captured images of spectators crowding overpasses and side streets, like scenes from a universe parallel to the audiences that had sat transfixed watching Simpson steadily pursue a record-breaking 2,000-plus yards rushing season as an all-pro back for the Buffalo Bills in the 1970s.

Simpson’s peaceful surrender in the driveway of his Brentwood estate contrasted sharply with the fate of Rodney King just a few years before. King’s arrest came after a videotaped torrent of police baton blows. The incident touched off a shockwave culminating in riots following the acquittal of the officers charged with beating him — and set the stage for a legal counter-reaction by the Simpson jury.

The former University of Southern California gridiron star, always the only suspect in the murders of his white ex-wife and her lover, faced an uphill battle during the lengthy legal ordeal that proved a ratings bonanza, with sub-plots unfolding like a Hollywood script throughout the trial. The courtroom theatrics introduced America to the Kardashian family, prosecutor Marcia Clark, slacker Kato Kaelin and media-friendly Judge Lance Ito. Harvard Law Professor Alan Dershowitz and legendary defense attorney F. Lee Bailey played supporting roles.

In spite of evidence showing serial physical abuse of his ex-wife, the jury delivered a non-guilty verdict based on reasonable doubts planted by Simpson’s legal “Dream Team,” led by courtroom impresario Johnnie Cochran. The defense exploited sloppy and perhaps criminal handling of evidence by police along with their own evidence of racist attitudes among L.A. police, including the lead investigator, Mark Fuhrman.

The jury, made up of 10 Blacks and two whites, voted to free Simpson after prosecutor Chris Darden notably asked the defendant to try on the notorious “bloody glove” found at the crime scene as well as its match police said they found at his home. Simpson visibly struggled to pull the gloves over his hands.

“If the glove don’t fit, you must acquit,” declared Cochran. And the jury agreed, setting off split-screen coverage of Black audiences cheering the verdict while whites sat in silent shock at the decision.

To Harvard Law Professor Ronald S. Sullivan Jr., the government undermined their own case by overreaching, especially in the questionable handling of physical evidence, some of it possibly planted, others obtained with warrantless searches.

“They framed a guilty man,” said the noted defense attorney and legal expert. At the time of the 1995 verdict, he was a young public defender in Washington, D.C., working in an office “where a multi-racial, multi-ethnic crowd cheered the verdict,” he said.

TV news reporter and host Tanya Hart, who left WBZ in Boston for the West Coast in 1990 and covered the trial for E!, made an on-air prediction of acquittal not long after Cochran craftily had the case moved from the courthouse in predominantly white Santa Monica to Downtown Los Angeles.

“If you had taken the same evidence to a white Santa Monica jury, he would have been convicted,” said Hart. “The venue was the difference between guilty and not guilty. I was attacked for saying he’d walk but when he was acquitted, they ran my commentary every ten minutes.”

Looking back on the case, Ife Franklin, 64, a Roxbury artist currently working in the field of combatting domestic violence, said she both admired Simpson for his accomplishments on and off the football field and condemned the abuse of women in his life.

“I always believed O.J. Simpson was guilty, but that didn’t stop me from understanding how far he’d traveled to become a success. I got a lot of heat for the perception that I was being a traitor to the Black community,” said Franklin.

“Unfortunately, it often takes cases like these involving a celebrity to shine a spotlight on domestic violence,” she said.

Simpson, who grew up in the tough Potrero Hill projects in San Francisco, drew widespread support from the Black community despite fashioning himself during his career in sports, broadcasting, advertising and movies as the colorblind creation of a post-racial, post-civil rights society.

“I’m not Black, I’m O.J.!” he once famously exclaimed. Talking about endorsements in an interview with the New York Times, he said Hertz and other companies liked the fact that he was so universally likeable. “People identify with me, and I don’t think I’m that offensive to anyone,” he said. “People have told me I’m colorless. Everyone likes me. I stay out of politics. I don’t try to save people for the Lord and, besides, I don’t look that out of character in a suit.”

But after the trial, the days of milquetoast whites yelling, “Go, O.J., Go!” as he sprinted down an airport concourse in a three-piece suit, vaulting over baggage enroute to the Hertz counter were over. Appearances in TV serials and movies like “Roots,” “Naked Gun,” and “Towering Inferno” were replaced by a seemingly endless string of documentaries and books about the murder case, including “The People vs. O.J.”

Setting aside the legal woes that tainted his career, University of Massachusetts Boston Professor Joseph Cooper called Simpson’s athletic accomplishments “transcendent” and his social impact “profound,” putting him in a category with such pioneers as track star Jesse Owens, boxing champion Joe Louis and baseball great Jackie Robinson. Like the others, Simpson’s star appeal off the field came at a crucial moment in race relations, he said.

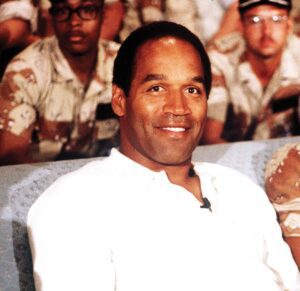

O.J. Simpson is interviewed by the press after leading USC Trojans to 14-3 Rose Bowl win. PHOTO: Los Angeles Times Photographic Collection, UCLA

“The particular times where all four came into prominence were moments of great social change,” said Cooper, who holds the J. Keith Motley Chair of Sport Leadership and Administration.

Owens challenged the Nazi myth of Aryan supremacy at the 1936 Olympics, Louis stood up to racial bullying to win the heavyweight championship and serve in World War II, and Robinson broke the color-line in “America’s Game” while maintaining his equilibrium amidst racial abuse.

“O.J. was the one of the first examples of the post-civil rights era uses of Black athletes as a commercial spokesman,” said Cooper. “He used his athletic exploits and charismatic personality to appeal to the broadest possible audiences. Coming along at a tumultuous time, he showed how sports served as a unifying influence on society.”

After his acquittal in 1995, Simpson moved to Florida to raise his children, but his legal woes were far from over. He was found liable for the murders in a 1997 civil case brought by the Goldman family and never fully repaid the $33.5 million in damages he owed.

In 2007, troubles loomed again after his arrest for invading a Las Vegas hotel room to recover what he said were sports memorabilia stolen from him. The courts disagreed. An all-white Nevada jury convicted him of armed robbery in 2009 and the judge sent him to serve nine years in prison.

Simpson’s rapid-moving life trajectory — from wearing leg-braces as a child afflicted with rickets to sports stardom in college and the pros to multi-media TV and film celebrity — slowed down after serving his time. He moved to Las Vegas and lived off his pensions from the NFL and the Screen Actors Guild. His four children — Arnelle and Jason from a marriage to his high school sweetheart Marguerite Whitley, and Justin and Sydney from his union with Nicole — grew up. All survive him along with three grandchildren.

He amiably signed autographs and took photos when he ventured in public, his athletic body now thicker and slightly hunched over, his face puffier.

“O.J. is a complicated figure,” said Professor Sullivan, reflecting on Simpson’s status as a one-time racially neutral figure who became a symbol of racial bias in the criminal justice system. “He articulated a vision of himself as post-racial celebrity so it’s quite ironic that he became a cause célèbre for racial inequity.”