Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery

L'Merchie Frazier in conversation with artist Napoleon Jones- Henderson

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/NJ-H_1-861x1024.jpg)

View Banner Art Gallery

Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery

Sponsored by City of Boston | Mayor Michelle Wu

This is the 17th interview in a weekly series presenting highlights of conversations between leading Black visual artists in New England. In this week’s installment, artist L’Merchie Frazier talks to artist Napoleon Jones-Henderson. The interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

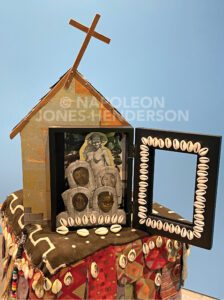

Roxbury-based Napoleon Jones-Henderson is a weaver and multimedia artist well-known for his role in AfriCOBRA (African Commune for Bad Relevant Artists), an artist collective established in Chicago, Illinois, in 1968. He holds a Master of Fine Arts from Maryland Institute College of Art and a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the Art Institute of Chicago. Earlier this month, he was awarded the Center for Art, Research, and Alliance Fellowship, a $75,000 grant created for mid to late career artists and artists’ legacies. He plans to curate an archival collection of the AfriCOBRA collective.

L’Merchie Frazier: Napoleon, what about Chicago and the Midwest did you bring with you as you relocated to Boston, specifically Roxbury, in 1974?

Napoleon Jones-Henderson: I brought the spirit of my mama and my daddy and all the folks from Alabama, where she was born. And the whole electric and spiritual energy of Chicago that I was embraced with throughout my life … people like Hoyt Fuller, Margaret Burrows, Gwendolyn Brooks and Oscar Brown Jr.

All the artists who I began to associate within a young adult context — Jeff Donaldson, Wadsworth Jarrell, Lester Lashley and Barbara Jones[-Hogu] — were the spirits and energies that came with me when I came here. So, coming here and meeting people like yourself, Dana Chandler, Gary Rickson, Paul Goodnight, Ekua Holmes, Nancy Baptiste — I can go on for the next half hour about all the people I met here. Hakim Raquib, Susan Thompson, who have been really pivotal in my being able to be comfortable here in Roxbury — similar to how it was in Chicago, a new family or an extended family. It’s definitely been a healthy, physical, mental, aesthetic, spiritual and intellectual benefit to me to be here. Coming here from Chicago was simply a different visual landscape, because all the same energy that existed for me in Chicago, with the exception of Miss Maxine, my mama, manifested itself here in Roxbury.

Can you tell us why you chose to not only represent yourself as an individual but as an institution?

I’ll tackle the institution piece. It was brought to me by the community that embraced me when I came here — Ekua, Paul, Gary Rickson and all those artists. Coming and congregating in my home, my studio, my sacred space, they made me aware of the fact that I had a collection of works that needed to be shared beyond my walls. That was around ’75, ’76, because I got the house in 1975. They said other artists should be able to see and access this. So, from that kernel being planted, it sprouted, and, of course, you know the metaphor of the ear of corn and all the kernels that are on it. I then instituted, put together, the Resurgence Studio of African and African Diaspora Art, because what I have are bodies of work that have been given [to me] and I’ve exchanged [works] with some artists — works from artists all over the world.

I met Allan Rohan Crite at his home and saw the kind of environment he was living in was the same kind of environment that I was living in. The institute just came out of the natural flow of how I lived my life, and the sharing of that life with the larger community and these individual artists who were here saying look: more artists need to see this. Not only is it artwork, but it’s a collection of over 3,000 books, manuscripts, posters and all kinds of other stuff — ephemera that we’ve all created in our lives as a community of imagemakers. Fortunately, right now a little team of archivists are trying to put it in some order. But it was just the way I lived.

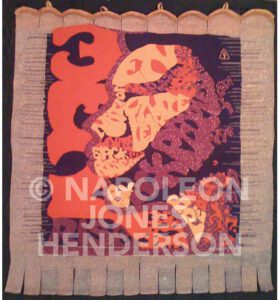

How do you see yourself in dealing with the mediums of fiber, textiles, enamel and copper as your canvas — how do you see how you have influenced that canon?

I accept that because others have indicated to me that I have some influence. I’ve contributed to the collective influence, and I say collective in the sense of you and Paul and all the other artists who I know and have spent my life communicating and carousing with. AfriCOBRA is the pivotal foundational base under which my images flow out.

Our mission was about what is it and what role does the image that we create as a collective of artists contribute to the liberation of the African body internationally? That was in the heat of the civil rights period. And one of the important elements that the 10 of us who made up AfriCOBRA were very clear [about] was we were not of the ilk of nonviolent marching and being hit upside the head and all those other things. We [asked], how can we as visual artists, visual imagemakers, contribute to this movement of liberating the humanity of African people across the world? And if what we are committed to doing is making images, then those images have to mean something to the people.

Our first collective body of work was the Black family, because everything else stems from there. We have a philosophy that we shaped and put together that directs what we do as visual imagemakers, and we have a set of aesthetics. One of those very important elements of our esthetics is our Kool-Aid colors and those sorts of things.

View Banner Art Gallery