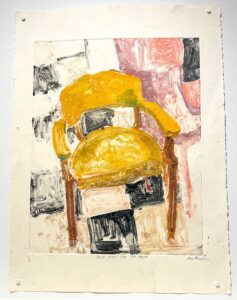

Painter Josué Bessiake is obsessed with the dynamics of the ordinary. In his current show at Gallery NAGA, “Josué Bessiake: A Bird’s Last Look,” the ordinary takes the form of chairs. Chairs front and center in abstract styles, chairs in the background at a dinner party, some occupied, others abandoned. In the intimate exhibition, Bessiake explores the relationship between body and object through the lens of these everyday furniture pieces.

“When the body interacts with an object, it fills that object’s purpose,” he says. “I’ve been thinking about what happens when the body is absent from an object — is it just an abstract shape?”

It’s an artistic version of the age-old question, if a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to hear it, did it make a sound? Bessiake probes how humans’ relationships with objects put them into certain categories and denote that something is useful but perhaps not art, or vice versa. Where do these rules come from, and what meaning do they really have?

“I’m very interested in the labels that we give objects, and the rules that we impose on an object when you give it a label,” says Bessiake. “To call something a chair already has years of history of how you’re supposed to interact with it, because we’ve labeled it a chair, but it’s really just this beautiful abstract form.”

Bessiake’s artistic journey began at age 3 when he was entranced by a Peter Paul Rubens exhibition in New York. From there, he began tracing cartoons off the family television and drawing in every spare moment. Now he works most often in oil paintings and charcoal drawings and is beginning to branch out into sculpture. Bessiake is in his senior year at Montserrat College of Art in Beverly and has a post-grad residency lined up in upstate New York.

The artist’s parents immigrated to the United States from Côte d’Ivoire in West Africa. Though Bessiake was born in the United States, that African heritage permeated his upbringing. He says his father would often tell them, “At home you are in Africa, outside you are in America.”

The work in “A Bird’s Last Look” also is highly personal. Bessiake paints himself, his friends, his studio and several moving images of his father. In two juxtaposed pieces, there is an oil painting depicting Bessiake sitting in a chair and his father standing beside him. Only his father’s leg is visible, a strong and stable presence next to the energetic movement of Bessiake. Next to the painting is an oil-on-paper piece depicting the same scene but without Bessiake. The chair next to his father is empty. This contrast encourages viewers to note the differences in the scenes when the chair is occupied and unoccupied.

Bessiake’s work is deeply cerebral, but it’s also guided by intuition and emotion. He says his process evolves organically, in small movements that are felt rather than planned.

“A Bird’s Last Look” is on view at Gallery NAGA on Newbury Street through April 27. The artist hopes that above all, viewers engage emotionally with the work.

“When you really are forced to take in the work and be still with it, that will force you to interact with it in an emotional way,” he says. “I’d rather have the object itself be compelling enough to get you to interact with it, and then the central meanings behind it can only add to that.”