‘Firelei Báez’ — Shifting perspectives of history, exploring legacies of the African diaspora

“Firelei Báez,” the spellbinding exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston through Sept. 2, is the first U.S. survey of this Dominican American artist, whose works are often described as history paintings for our time.

Báez, 43, who lives and works in New York, says that her works are “meant to create alternative pasts and potential futures … to provide a space for reassessing the present.”

Firelei Báez, “A Drexcyen chronocommons (To win the war you fought it sideways),” 2019. Installation view. The Joyner/Giuffrida Collection. Image courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth, New York. PHOTO: Phoebe d’Heurle. © Firelei Báez

Steeped in references to Afro-Caribbean culture and history and endowed with incantatory titles, her works are often populated by fantastical female figures — ciguapas — of Dominican folklore, feral and uninhibited guides to untold or overlooked stories. Lithe and athletic or statuesque, with limbs adorned with flora and fauna or coated with hair, they are agents of power and freedom, stirring the reimagining of history. The viewer, too, becomes active in the works, which with their conceptual and visual intricacy, sensuous immediacy, and sheer beauty command close attention and inspire reflection.

In miniatures as well as in wall-size murals, Báez often employs manual practices, including West African indigo printing brought to the Americas by enslaved people, and her technique of pouring pigments on non-absorbent Japanese Yupo paper, which yields whirls of marbled colors. Organized by Eva Respini, deputy director of the Vancouver Art Gallery and formerly the ICA’s chief curator, and Tessa Bachi Haas, ICA curatorial assistant, “Firelei Báez” presents 40 drawings, paintings and installations made over the past two decades. It will tour to the Vancouver Art Gallery in November, and in 2025 travels to the Des Moines Art Center.

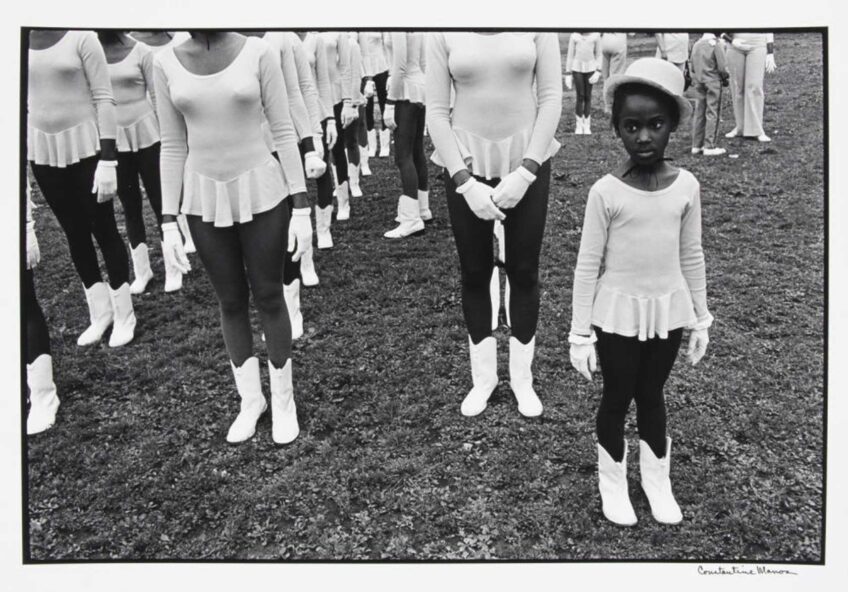

Firelei Báez, “Sans-Souci (This threshold between a dematerialized and a historicized body),” 2015; Pérez Art Museum Miami. PHOTO: ORIOL TARRIDAS, © FIRELEI BÁEZ

Opening the ICA exhibition is a 2014 installation that conjures a ruined palace that was build in 1813 for a leader of the Haitian Revolution against the French colonial government. Its tactile surfaces combine stripped, cracked wood with delicate indigo images of floral patterns and parapets. A crisp white arch invites visitors to enter and view its fully painted reverse side.

Two other installations, made in 2019, also invite visitors in. In one, they observe themselves in a Baroque hall of mirrors, flanked by figures named for waxing and waning moons and concealed behind bursting rays of color. Another is a blue, star-lit grotto constructed of perforated tarps used for emergency shelters.

Organized chronologically, the exhibition devotes two galleries to works on paper. An array of female portraits presents opulence as a form of resistance. Mocking a colonial law requiring Creole women to cover their hair, some subjects are crowned with regal, ornately coiled turbans. Others have wild clouds of hair or spiraling ringlets. All have piercing eyes.

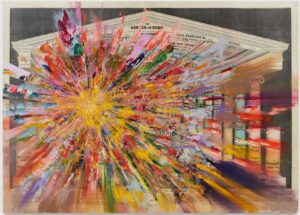

Báez often overlays dry documents that measure, map, chart and study lands and buildings with images of freedom, life and beauty —

including sensuous vegetation and ecstatic supernova bursts of color.

Firelei Báez, Untitled (Temple of Time), 2020. Oil, acrylic, and inkjet on canvas. 94 1/2 × 132 3/8 × 1 5/8 inches (240 × 336.2 × 4 cm). Wilks Family Collection. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth, New York. PHOTO: Phoebe d’Heurle. © Firelei Báez

Tiny ciguapas overrun pages from obsolete books about Hispaniola, the island encompassing both Haiti and the Dominican Republic, inserting a past absent from these pages.

Such layering is visible on a grand scale in five galleries of paintings. In the 2019 work “the trace, whether we are attending to it or not (a space for each other’s breathing),” which refers to the Natchez Trace, an old Native American travel route later extended from Nashville to New Orleans by European traders, a ciguapa with a head of tropical flowers springs across a diagram of railroad trestles. As her fingers rest on a track, it resembles a piano keyboard, evoking New Orleans. Also conjuring that city is “Untitled (Marine Hospital),” made in 2021, in which a fantasia of Mardi Gras feathers bursts from a diagram of the facility. A 2019 version engulfs the diagram with a surging wave, calling to mind Hurricane Katrina.

Sublime currents of lavender, gold and blue burst with show-stopping beauty in “temporarily palimpsestive (just adjacent to air)” (2019) and “Madeleine (Rupture rapture maroonage)” (2002), a recasting of an 1800 French portrait of a bare-breasted Black woman, here rendered in an arched panel like a saint, with only her indigo headwrap visible.

Concluding the exhibition is a new ICA commission, a Seaport-facing mural painted over a colonial map of Boston Harbor.

The exhibition catalog is itself a work of art. Complementing its essays are lustrous color plates that include closeups of exquisite details and, on uncoated paper, a sketchbook with the artist’s handwritten notes about each image.