Senate votes to confirm Providence native to seat on federal bench

Melissa DuBose reflects on her journey from neighborhood kid to U.S. District Court judge

On a recent Friday afternoon, Judge Melissa DuBose sat in her Providence home thinking about how she arrived at this moment: confirmed by the U.S. Senate to fill an opening on the U.S. District Court for Rhode Island.

“When I reflect on the process, I’m still kind of in a little bit of shock. I mean, it was so long, and a really, really, really difficult journey,” she said. “So, it feels good. I’m exhaling, but I’m not quite fully there yet.”

She wore a coral sweater, a departure from her Black judge’s robe, and her Zoom background revealed an elegantly decorated home complete with potted plants and a smattering of framed pictures.

For well over a year, the judge maneuvered the judicial hoops it would take to get her from her current standing as an associate judge on the Rhode Island District Court to the federal bench. The process involved speaking before a panel, meeting with the governor, testifying publicly and participating in a contentious Senate hearing.

She was confirmed on March 12 when the U.S. Senate voted 51 to 47, but DuBose still needs to receive the commission from President Joe Biden, which she expects will happen in December. When that finally occurs, she will make history as the first Black and openly LGBTQ+ person to hold the position. That designation is a point of pride. But, she admits, it makes her “cringe” just a little.

“Sometimes when people lead with the identity,” she said, “it kind of frames it in a way where it may not be about merit.”

She recognizes that we live in a time where “these labels carry weight, both positive and negative,” she said, and people need to see a Black woman or an LGBTQ+ person putting themselves in spaces where they were historically unwelcome. At the same time, she knows she will have to balance her desire to represent well with demonstrating that labels can be set aside to highlight qualifications and experience instead.

Having never clerked for a federal judge, DuBose’s path to the U.S. District Court for Rhode Island was nontraditional. In fact, she didn’t set out to enter the field of law at all. But once she rose through the ranks, the opportunity to join the federal court felt both like a once in a lifetime opportunity — there have only been 25 judges in the U.S. District Court for Rhode Island, ever — and a personal calling.

“I just thought, well, if not me, then who? And why not?” she said. “And so that’s kind of what led me to have the courage to say: I’m going to put myself out there and go through this very public process to demonstrate that a poor girl from Providence can do things.”

DuBose grew up in Mount Hope, a small hamlet sandwiched between Hope Street and North Main Street in Providence. Hers was a “magical” neighborhood, teeming with kids scurrying about, aunts and uncles who loved her, and neighbors who looked out for each other.

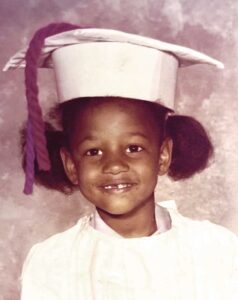

Judge DuBose grew up in the Mount Hope neighborhood of Providence, Rhode Island. PHOTO: COURTESY OF JUDGE DUBOSE

Although her family was poor, she said she never wanted for anything. Instead, she relished her diverse public school education and spent hours at the Rochambeau branch of the Community Libraries of Providence, which provided a respite from her cramped six-person household. In the library’s Russian room, she said, she did her homework, tucked into Judy Blume books and even struck up a friendship with older Russian adults.

“I think one of the greatest gifts of growing up in that environment is the fundamental trust that I have in the goodness of people,” she said, her face lighting up as she recounted her childhood. Interacting with people of various socioeconomic backgrounds taught her that the world didn’t have to be in silos.

Providence has changed a lot since then, but no matter how far up the ladder she moves, DuBose said her family keeps her humble. She will always be a cousin, a sister, an aunt.

After graduating from Providence College, she was offered an opportunity to teach history and civics for Providence Public Schools and, ever academically curious, she took it. She delighted in the symbiotic respect, curiosity and love she received from her high school students. It was “infectious,” and it vitalized her as she stood at the front of the classroom giving lessons on Eastern philosophy or political theory.

A tragic incident changed everything.

When a student of hers murdered another student about four years into her teaching stint, DuBose was rattled. The young teacher was forced to confront her own misconceptions about the children and the lives they lived outside of school. The student, like many others, she learned, had been involved in gang activity, which DuBose said she was unaware of because she hadn’t grown up in an area that faced such challenges.

When her students came to her for answers or opened up about their experiences, DuBose felt a sense of helplessness.

“I had to figure out a way to be an advocate in a way that makes sense,” she said. Watching her student serve time for the crime, the teacher decided she wanted a seat inside the inaccessible juvenile system to better advocate for her students and raise awareness about the procedures.

She signed up for evening division classes at the Roger Williams University School of Law, which she juggled alongside teaching full time and parenting two babies with her partner. After graduating in 2004, she took on a job as a juvenile criminal prosecutor, to the dismay of her students who felt betrayed by her decision.

This is how she explained her choice to them: “You’re as likely to be the victim of a crime as you are to be the person who’s committing the crime. I want to make sure that you know that the victims have an advocate. That’s the state’s job — to make sure that we do justice for you.”

Thereafter, her career pivoted slightly. She worked as an in-house lawyer for Schneider Electric corporation, before being recruited to apply for a vacancy at the Rhode Island District Court, which she calls “the people’s court.”

There she teamed up with other judges of color to create the Committee for Racial and Ethnic Fairness in the wake of the summer of 2020, a time when it was lonely being the mother to two Black sons, yet unable to comment on the situation due to her status as a judge. The Committee of 12 judges grapples with questions around fairness and access to justice for Rhode Islanders, and engages with the community to learn how to better serve it.

Over a year ago, DuBose was offered yet another step up: taking over Judge William E. Smith’s seat on the U.S. District Court for Rhode Island. When Smith announced his plans to retire and take senior status later this year, Sen. Jack Reed and Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse together recommended DuBose as his replacement, the Boston Globe reported.

The road to get here was long and winding, DuBose said. It included a controversial Senate hearing in which U.S. Sen. John Kennedy (R-La.) asked DuBose repeatedly if she was “still a Marxist.” In an interview two decades ago, DuBose told a Brown University newspaper reporter that she had gone through a “Marxist phase.” She responded by saying, “I am not, nor have ever been, a Marxist,” the Washington Blade reported. DuBose declined to comment on the hearing.

At every step of the way, DuBose has leaned on her partner of 25 years and her two sons for support, she said, as well as her sisters. And when it comes to taking care of her mental health, her comforts of choice are Mario Kart, “bad” TV shows like “Love is Blind,” and, of course, reading.

DuBose said her younger self would look at her with recognition, laughing at the risks the older DuBose has taken throughout the course of her 55 years. For now, DuBose said she’s not aiming any higher than where she hopes to be in December. Ask her in 5-10 years and her answer might be different.

What she does know, she said, is that at some point, she will likely return to the classroom. “I think it’d be amazing,” she said of potentially trading in “Judge DuBose” at a bench for “Ms. DuBose” standing in a classroom filled with energetic students buzzing with ideas.

“There’s nothing like it in the world,” she said. “There’s just no better place.”