Decades-old collective uses art to shift public narratives about Haiti

In the late 1980s, a tense political situation in his home country of Haiti left visual artist Charlot Lucien with little hope for his future. He was in his mid-20s at the time and involved in political cartooning at a moment when the country’s leaders scorned political expression through media. So, he left.

“I do not consider myself a political refugee,” said Lucien, who teaches history at the University of Massachusetts. “However, the circumstances weren’t favorable to either my professional evolution or to my artistic evolution.”

He came to Massachusetts where, in 1994, he began working with other Haitians in the state to bring together artists hailing from the Caribbean nation, some of them well-known, others teachers of art. In January 1995, Lucien said, a group of over 60 Haitian visual artists, writers, storytellers and performance artists convened, forming what is today known as the Haitian Artists Assembly of Massachusetts.

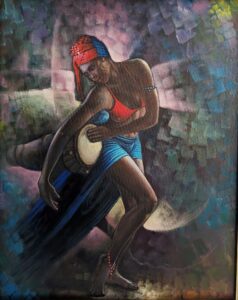

The group comprises artists operating across New England who aim to promote new narratives about Haiti that go beyond a “powerless state” in need of handouts, Lucien said. HAAM achieves this by holding art exhibits and workshops and creating opportunities for collaboration. Most recently, the collective organized an art exhibit called “Brush Strokes for Peace” at Boston University’s Howard Thurman Center for Common Ground, curated by artist Joseph Chery.

The goals of HAAM are to discover New England-based Haitian artists and nurture fellowship among them, Lucien said. But the group’s primary focus is to intentionally conceive a “new narrative about what art could reflect from Haiti’s history and culture, and how we can elicit more discussion and debates about Haiti in a different manner.”

Since its founding, the group has evolved, Lucien said, adding more women artists to its circle and taking a more active role in social and civic engagement. Lucien and other Haitian artists have long witnessed “many instances of either political stereotyping of the Haitian community or Haitians in general,” discrimination and a misrepresentation of the Haitian people, he said. HAAM has also evolved to respond to this through art. Where artists first began by depicting landscapes and abstract shapes, for example, they have now turned to creating work that reflects their stance on policies and racism.

In the past, when Haiti has been rocked by calamitous natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes, Lucien said HAAM artists in New England have responded by offering artworks during fundraising campaigns to raise money for foundations working directly to aid Haitians on the ground.

During humanitarian crises, such as the one currently plaguing Haiti, Lucien and other artists have collaborated with civic leaders, written position papers, signed petitions and lobbied with those in policy-making positions. The group has also partnered with organizations on the ground, all with the objective of uplifting Haiti.

Lucien said if people continue to be told that Haiti is a crippled nation always in need of assistance, both well-meaning people and those of bad faith will continue to only view it that way, reducing the entire culture to an inaccurate monolith and potentially mistreating Haitians. If no one works to change that narrative, Lucien said, the consequences will be detrimental.

“We are failing an opportunity to negotiate, to collaborate between equals and to get valuable insight,” he said. “So, by letting people construct a negative identity [of] Haitians, this is going to be bad for Haitians. It’s also going to be bad for the U.S. or for any host community [that] intends to be partners or collaborators.”