Banner Sports sponsored by Cruz Companies

When people hear “martial arts,” they mostly think of Bruce Lee, the legendary martial artist who became an international star of the silver screen. To this day, I find it difficult to turn off a Bruce Lee movie. And I know that I am not alone. The man was a legitimate superstar athlete who had to break down a myriad of racial and cultural barriers while developing his exquisite skills. His legend reached iconic status when he died at the tender age of 32. But so much of his life centered on teaching others the craft he had mastered. His list of students is a Who’s Who of the martial arts world.

Europeans coined the term “martial arts” to refer to Mars, the Roman god of war. Despite the common association with Asian culture, all cultures have their own forms of fighting arts systems and rituals.

But long before Bruce Lee, Black martial artists were denied their place in the sport’s history.

During the wake of the Civil Rights Movement, martial arts developed but did not do so in conjunction with the movement. According to scores of Black and Hispanic people presently or recently involved in the martial arts sphere, people of color have been a dominant force in organized tournaments since the 1960s and ’70s. And the same prejudice and racism that plagued the sport back then is still with us today. The true culprits in this scenario are those who presently control martial arts. It is hard to keep track of the alphabet soup of organizations that claim to be the ruling authority of martial arts, and just as challenging to go after the racism and discrimination they perpetuate.

Generations of their victims have spoken out on this issue, but like so much of modern-day thinking, people hear the words racism and discrimination, and they turn blind and deaf to the problem.

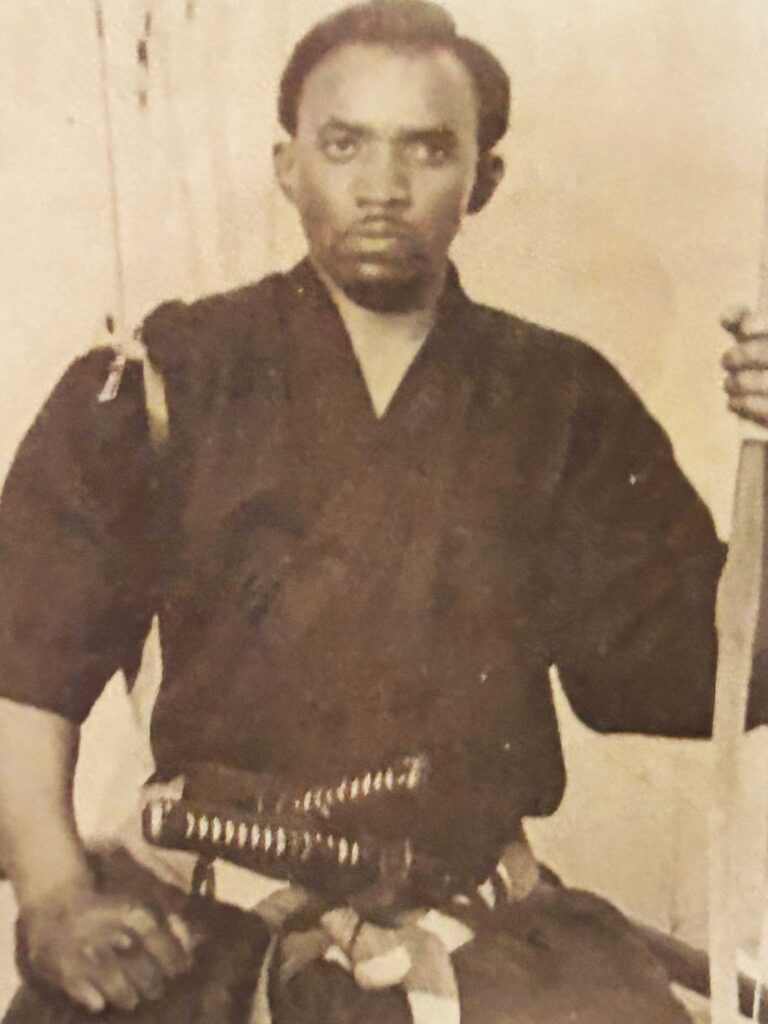

A recent conversation with Ronald Jr. and Gregory Duncan, the sons of the late martial arts legend Ronald Duncan — the father of American Ninjitsu, the first American Ninja — spoke about their father’s legacy in a recent interview.

“After serving his country as a United States Marine, my father honed his martial arts skills and became a multiple black belt martial artist,” Ronald Jr. said. “He and my mother, Betty Duncan, who played a major role in his career, produced five children, and my father trained each one of us in martial arts skills. Martial arts are more than just a practice; they’re a way of life.”

“My father did not see color, and we were raised to respect all people,” said Gregory Duncan. “Our school, Duncan Martial Arts, operates out of Union, New Jersey, and trains students from ages four to 74. My father’s life was tied up in his teaching. It was his true passion to bring martial arts to people from all walks of life.”

Gregory Duncan’s father is considered one of the great martial arts pioneers. Born in Panama in 1938, he gained national recognition for his ninjitsu skills, which he introduced in 1964 when he opened his first martial arts dojo in Brooklyn, after operating out of the St. John’s Recreation Center for five years.

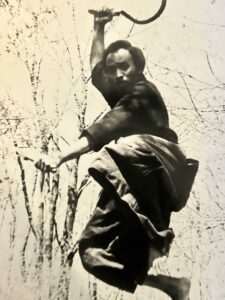

Following the introduction of martial arts to the American scene, Professor Duncan stepped onto the global platform at the International Convention of Martial Arts in New York City in 1968. This followed landmark appearances at the 1964 and ’65 World’s fairs. His groundbreaking demonstration of ninjitsu techniques drew rave reviews from masters and influencers around the world.

He captivated the audience, thus gaining the title of “Father of American Ninjitsu.” But despite acknowledgment from the Japanese government, he faced exclusion from Black Belt Magazine for several years due to a disagreement with the publication’s editor. The publication later recognized him as a martial arts pioneer. It was his unwavering commitment to pioneering, his teaching of ninjitsu, that solidified his place in history. Ronald Duncan played a key role in popularizing ninjitsu from the 1970s to the 1990s.

His global fame skyrocketed with television appearances on ABC’s Wide World of Sports in the Oriental World of Self-defense at Madison Square Garden. In the event, hosted by Aaron Banks, Duncan displayed his vast martial arts expertise, including his proficiency in various disciplines of Judo, Hakko Ryu Jujitsu, Dai-Nippon Jujitsu Ryu, and more. Ronald Jr. and Gregory both state: “Our father had a degree of creativity that allowed him to pioneer within the early generations of the martial arts.”

He was also renowned for his mastery of knife-throwing, firearms, and stealth techniques. His composed demeanor and martial arts abilities helped him pioneer the Way of the Wind martial arts system that is recognized worldwide today. Duncan was a man of great integrity who spoke his mind on his craft and the difficulties of dealing in the world of the 1960s up until the day he died. The sad part was that the media of that time chose to center on his remarks about race while missing his true message.

Ronald Jr., Gregory and their three siblings (Valarie, the eldest, Deborah, and Christina, the youngest) live in the legacy their famous father created.

“Our father had the courage to speak out against the wrongs of society throughout his life,” said Ronald Jr.

“He taught us to be brave and to stand up for what we believe,” Gregory said. “These are the principles that we operate on to this day.”

Brother Ronald also points out: “My father taught each of his five children to use their martial arts training to defend themselves — a valuable tool needed to survive the tough streets of Brooklyn, N.Y.”

Ronald Duncan is part of a martial arts legacy that includes Black pioneers like Moses Powell, Vic Moore, Karriem Abdullah, Joe Hayes, Chaka Zulu, Fred Hamilton, George Cofield, Steve Muhammad, Ron Van Clief, and many more.

They all suffered from racism and discrimination in some way, shape, or form but refused to let it prevent them from reaching legendary status in martial arts. This column is a tribute to their determination to succeed despite the racism and discrimination they tried to destroy.