If anyone says you can’t be both a journalist and an activist, Sarah-Ann Shaw proved you could be. What’s needed is determination and integrity — but not necessarily a driver’s license.

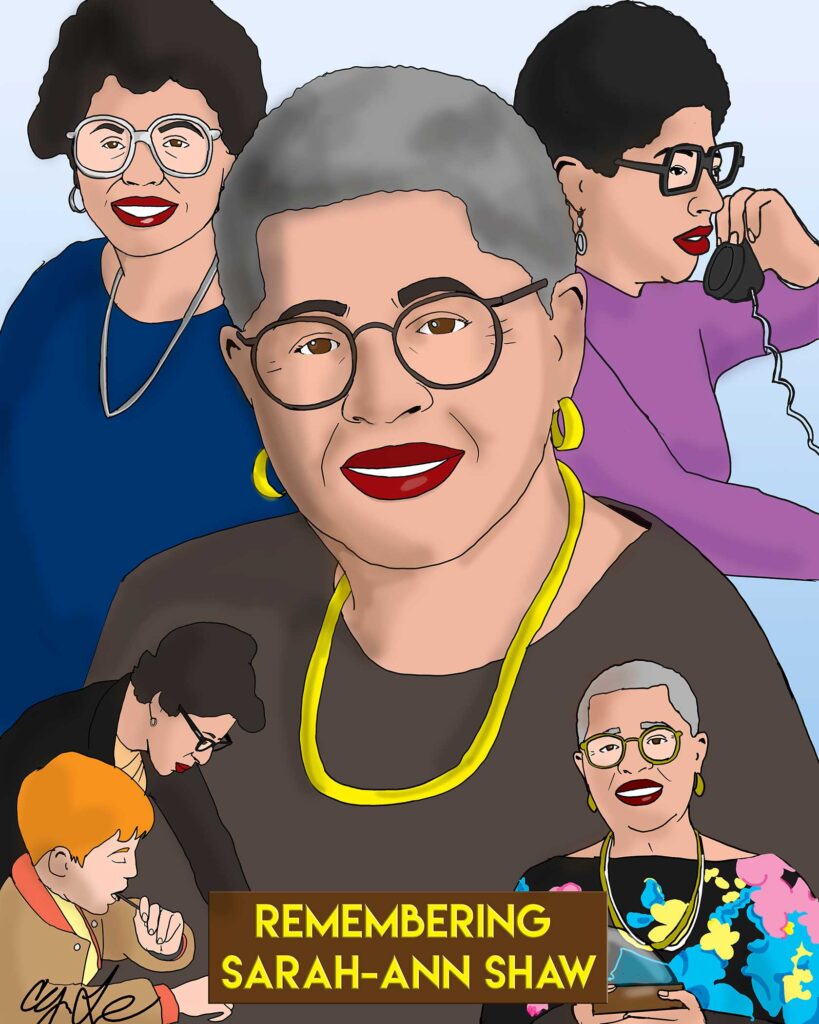

Shaw, who died at 90 on Saturday, was the first Black female TV reporter in Boston. Before that, she was a civil rights activist, which she never stopped being.

“I don’t think there was any conflict the way she practiced it,” said Carmen Fields, also a longtime Black female journalist in Boston, who calls Shaw her “journalistic godmother.”

“She was in favor of fairness and equal treatment. We were practicing journalism during the time when that was not always the case,” Fields said of the 1970s. “White people were treated differently and usually more favorably than people of color. She was balancing the scales and doing justice.”

Born in Roxbury in 1933, Shaw’s activism blossomed in the 1960s when she headed the Northern Student Movement in Boston, a tutoring arm of the Civil Rights Movement affiliated with the Congress of Racial Equality and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

She moved to television in 1968 when she was asked to host “Thinking Black,” a one-shot TV special about Black art and culture produced by the forerunner to PBS, according to a 1973 article by Kay Bourne, the Banner’s longtime arts and entertainment reporter.

The show aired on Boston’s WGBH just prior to the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Afterward, WGBH asked Shaw to join what became “Say Brother,” now “Basic Black” and one of the longest-running Black shows on television.

That put her among a small cadre of African American reporters and photographers who were suddenly recruited by major media outlets in the unrest following the King assassination; jobs they had previously been kept out of.

Shaw moved to WBZ the next year, and stayed until her retirement in 2000. To the shock of TV reporters working today, she never drove a car, and took the bus between the station and her Roxbury home.

That’s how she became my substitute mom.

Growing up in a Chicago household similarly immersed in the Civil Rights Movement, I moved to Boston in 1987. I was relieved that I would no longer have to chauffeur around my mother, who was also a civil rights activist who didn’t drive.

I found out Shaw didn’t drive either, and needed a ride to an endless number of meetings.

I complied, and as our friendship grew, stopped complaining.

“She went to every meeting, whether there were 100 people there or three people,” said Fields. “She’d say, ‘Carmen, aren’t you going to the committee to do such-and-such?’”

Many of those meetings were of the Boston Association of Black Journalists, which she co-founded. The group predates the National Association of Black Journalists, of which she was also a founder — with an asterisk because she missed its first official meeting in 1975.

Her involvement in the group was not merely to find friends to hang with, but a very real calling for an industry that shapes public opinion to itself better represent what the nation looks like. NABJ recognized her work with its Lifetime Achievement Award in 1998.

Allison Davis, an NABJ co-founder, was a young reporter just starting out at WBZ in the 1970s.

“She was an extraordinary mentor to me and helped build a foundation of the organization,” Davis said from Washington, adding that Shaw was every bit as forceful in the newsroom.

“She would go to the assignment editor and tell them what the story was and what she was going to do, rather than them telling her what she should do,” she said.

Former WBZ photographer Ric Mac said the same was true when Shaw was in the field.

“There was a community meeting at the Harriet Tubman House,” he said of an assignment in the 1990s. “I was told by the assignment desk to head over there and just ‘spray it’” — news parlance for shooting quick video shots to be voiced over for a 30-second piece.

“But when I arrived,” he said, “I immediately saw Sarah-Ann mingling with the politicians and community members. She was already off the clock and attending the meeting as a concerned citizen. When she saw me, she grabbed my mic and said, ‘We need to do a few interviews.’ When I responded that the assignment desk only wanted a voice-over, she snapped back: ‘Not anymore, my dear. I’m here!’”

It’s near impossible to recount all the groups Shaw was involved in, and even more futile to list the thousands she put on TV. But the hallmark of her stories was that they focused on everyday people, not the rich and powerful. And the people of color she covered were not the buffoon caricatures or romanticized glitterati depicted elsewhere on the TV dial, but real folks.

Remarkably, she reported their stories without driving a car. I asked her once why she didn’t.

“I don’t know how,” she replied.

It was the only challenge I knew she didn’t take on.

Robin Washington is a former managing editor of the Banner and worked with Sarah-Ann Shaw at WBZ-TV in the 1990s. He is currently editor-at-large of the Forward.