A new proposal in the Boston City Council would memorialize Crispus Attucks, a Colonial-era figure embraced as the first martyr of the American Revolution.

The initiative to create a sculpture of Attucks would help more Bostonians, especially residents of color, identify with Black figures from Boston’s history, said City Councilor Brian Worrell, who represents District 4 and proposed steps to consider the new monument.

“What we see opens our minds up to what we can be,” Worrell said.

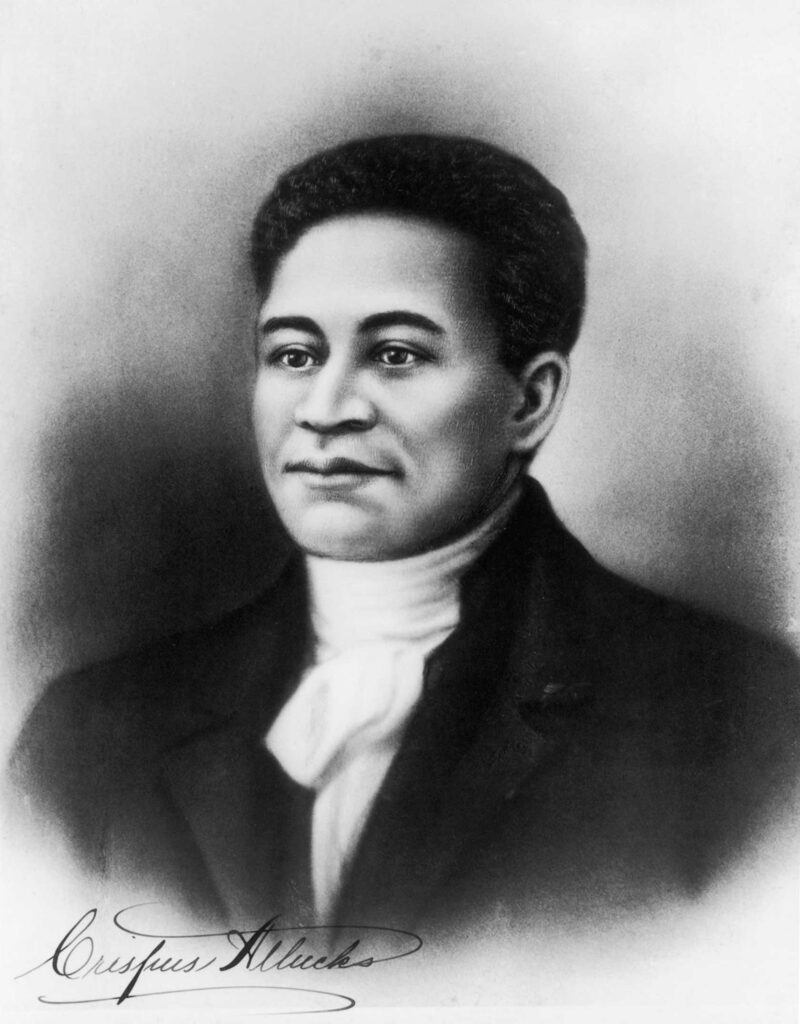

Lithograph by William L. Champney depicting an abolitionist view of the Boston Massacre. Crispus Attucks is the central figure.

Attucks, who was Black and Indigenous, was the first of five men killed in the Boston Massacre, an incident in the lead-up to the Revolutionary War where an altercation between Boston residents and British soldiers led to gunfire. The proposal would also create a Crispus Attucks day on March 5, the anniversary of the Boston Massacre.

A sculpture of Attucks would represent a step toward addressing the dearth of monuments showing Black figures in Boston. Only eight of the nearly 80 sculptures and monuments in the city are dedicated to Black figures or voices, according to the group Embrace Boston.

Within Boston, places like the Bruce C. Bolling Municipal Building in Nubian Square and the Edward W. Brooke Courthouse downtown bear the names of prominent figures of color, but Worrell said that a name doesn’t give enough of a sense of who a person was.

“Sometimes it’s not clear to our community that these were also people of color. That’s why the images are so important,” he said. “They see themselves and that can help spur that sense of reality, that we not only achieve those same levels or exceed those same levels of what’s perceived as that glass ceiling and shatter it, but to encourage our young people in the next generation to continue on.”

That lack of representation in culture and symbols was one of seven main harm areas identified by Embrace Boston in the organization’s Harm Report, released last month with the aim to support reparations for local Black residents.

In that report, Embrace Boston proposed that who is reflected in shared spaces speaks to who is valued and told they belong in Boston.

“I think that it really boils down, in many ways, to understanding where you fit in the overall American story,” said Greg Ball, director of digital strategy and production at Embrace Boston. “When we talk about monuments, they’re really just snapshots of the things that we deem important.”

Ball pointed to the monument to Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King on the Boston Common, which was unveiled last year by Embrace Boston. Before the monument stood there, Ball said many people didn’t know about the Kings’ connection to Boston and their time spent here.

“You get the opportunity to learn that, but not only do you learn that, you learn that on the Freedom Trail in downtown Boston,” Ball said. “When people come from all over the world to learn the story of America, they walk by this big monument to freedom fighting and to Black love. That’s a piece of our collective story that everyone gets to learn.”

Currently, a memorial to the Boston Massacre stands in Boston Common. That stone pillar, which bears the names of the five men who died and is decorated with a bas relief of the event, is often connected to Attucks, but Worrell said he hopes a monument dedicated specifically to Attucks would better capture his image and legacy.

“Crispus Attucks was an Indigenous Black man who was the first Patriot who died for our country,” Worrell said. “It’s the image we’re trying to get across, that is not certainly conveyed in that monument.”

Ball said it would be powerful to lift up a Black figure at the center of such a prominent event in Boston’s history.

“It gives us the opportunity to see a Black figure at the center of the beginning of the American Revolution,” Ball said. “I think that it’s essential to tell the full story of those times so that we get a better understanding of our collective history.”

According to various accounts, the death of Attucks and his companions followed a tense exchange outside the Old State House, where a crowd threw icy snowballs at soldiers who had been warned about possible violence in the wake of an incident involving a soldier who shot and killed a child.

Attucks, reportedly a big man who was said to be the son of an enslaved Black man and a woman from the Praying Indians band west of Boston, was apparently a prominent target for the frightened troops. A subsequent trial of the soldiers led to their acquittal, with future U.S. President John Adams serving as their defense counsel in an effort to prove to British authorities that their Colonial subjects believed in the rule of law.

Little concrete evidence exists about the early life of Crispus Attucks, said Peter Drummey, chief historian at the Massachusetts Historical Society. An enslaved man with the same name ran away from his enslaver in Framingham in 1750 and contemporary accounts suggest he is the Attucks who was killed in the Boston Massacre, but much of what happened between his supposed escape and his death in 1770 remains a mystery.

More information exists about Attucks through witness testimony following the massacre, but Drummey said those reports are sometimes conflicting.

But much of the heft of the legacy that Attucks carries to this day is not just as a sailor who was killed in the lead-up to the Revolutionary War, but as the symbolic figure he has become, Drummey said.

For Ball, those gaps create the opportunity to fill in the blanks, turning Attucks into something of a legendary figure.

“They say that certain people are legendary, that legends are when other people are telling stories about you,” Ball said. “I think this is one of those situations where people are telling those stories about a key important figure.”

That shift in perception can be seen in artistic representations of the event. In an engraving created by Paul Revere shortly after the Boston Massacre, those killed in the event — including one figure painted with a darker skin tone who is often tenuously pointed to as a potential representation of Attucks — are shown as innocent bystanders.

In the 1850s, however, a new image of the event showed Attucks as a central, martyr-like figure, more in line with the moniker of the “first Black patriot” that he has collected today.

That legacy remains an active one. The COVID-19 pandemic limited celebration of the 250th anniversary of the Massacre in 2020, but Drummey said many people saw an analogy between the actions of the British soldiers then and the police violence that people protested in 2020 in the wake of the murder of George Floyd.

For Ball, much of the work Attucks is connected with is still going on today and is now about shaping the country and its values.

“That fight is still going on,” Ball said. “The only thing is it’s not the American Revolution, but we’re still dealing with those ideals of creating America. I think America is in constant flux in the best possible way. We have the ability to build and create the country that we want to be.”