Hearing-impaired basketball star made history

Carlton Smith’s legacy continues off the court

Banner Sports sponsored by Cruz Companies

For every child who battles with hearing disabilities, Carlton Darien “Butch” Smith dedicates his story to you.

Born legally deaf, Smith would become one of the greatest players in Boston high school basketball history, breaking school scoring records along the way. Competing in a world of near-total silence, he thrilled teammates and fans with his court prowess as a guard and forward on a powerful Boston English High team in the early 1970s.

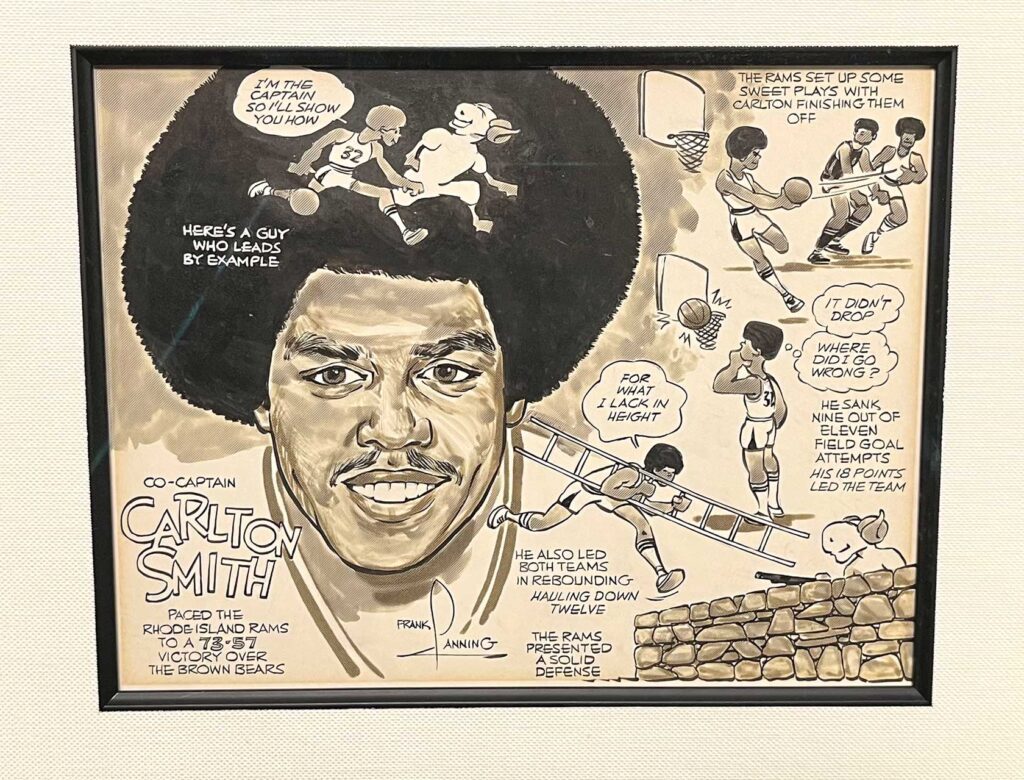

Led by Smith, known as “Dr. C” – a 6-foot-3 version of Julius “Dr. J.” Irving – the English team won the first Boston Shootout. He went on to play as a four-year starter at the University of Rhode Island and even to play with some of the Boston Celtics legends.

“I became aware of my situation at a very young age,” says Carlton, 69. “My mother knew of my condition and did everything she could to make me feel special, never allowing me to feel sorry for myself. She would always tell me, ‘You’re as good as anyone, and you can be as good as you want to be in this life.’”

Jacqueline Smith raised her son and daughter Rhonda in Roxbury as a single parent and with a sense of purpose. Besides his mother and sister and a few close friends, few were aware of his disability. And even when he began playing high-level hoops during his junior year, his deafness was rarely mentioned.

“I wore the old transistor earpiece, sticking the battery-energy pack in my pocket. But if I was in a noisy place, and people would call me, I could not hear them. Some took that as me being ‘stuck-up,’ but that was far from the case,” says Smith. “As the years went by and people would tell me that they spoke to me, and I didn’t respond, I would apologize to them and inform them that I just could not hear them.”

But living with deafness brought its share of unexpected cruelties. He recalls a mean-spirited pool manager at Franklin Field who told him to “take those ‘f-ing’ marbles out of your mouth and speak clearly.”

“I cried when I got by myself,” says Smith. “That man has no idea the damage he could have caused me. But thanks to my mother’s strength and her words of encouragement, I could go forward.”

“But I will never forget that moment. That man thought that I was dumb and could not speak. I don’t think to this day that he realized that when people are deaf, it affects their speaking skills. Over my lifetime, I have tried to pass on this lesson to young people with hearing disabilities by telling them, ‘Don’t let anyone put you down over a disability, no matter what the disability.’”

Lip reading helped Smith in school and, to a lesser degree, on the court. “I had to learn to read lips to understand my teachers, coaches and teammates. But that became even more difficult when I stepped on the basketball court to play. I couldn’t wear my hearing aid because my sweat would flow into it and clog it up,” he says. “But it is amazing how God will make your other senses more acute when you lose one. My peripheral vision became so good that I could see opposing players as they came up behind me trying to steal the ball.”

As a starter at English High, Smith averaged an astounding 25 points and 25 rebounds a game. In one unforgettable contest against archrival Boston Latin, he scored 39 points and pulled down 37 rebounds. In college, playing against a Boston College team made up of many of his Boston friends, he drained 22 points.

One of the most memorable moments of Carlton’s hoops career was having a chance to showcase his skills at the Boston Celtics summer camp at Millbrook and playing against Charlie Scott and the late Jo-Jo White.

He “impressed Celtics President Red Auerbach enough to be invited back for a longer look,” he says. “I was with a friend, and Red Auerbach called me over and sat me down next to him. It was one of the highlight moments of my basketball career.”

But before he could get that second look, he was “low bridged” in a pick-up game, seriously injuring his back. “Many pro athletes need to realize that their careers could end in a second,” he says with no bitterness.

Smith moved south to Washington, D.C., after his playing days were over before returning to Boston to help care for his ailing mother in 1983. His father passed away this past year.

He is now a successful businessman, owner of Advertising Business Concepts for 30 years, which produces promotional products and branded sportswear. Married to his wife Doreen since 1990, he credits basketball and the lessons he learned on the courts of Boston to a fulfilling career.

“I don’t want anyone to feel sorry for me,” he says. “I’ve met some wonderful people and had a great life.”