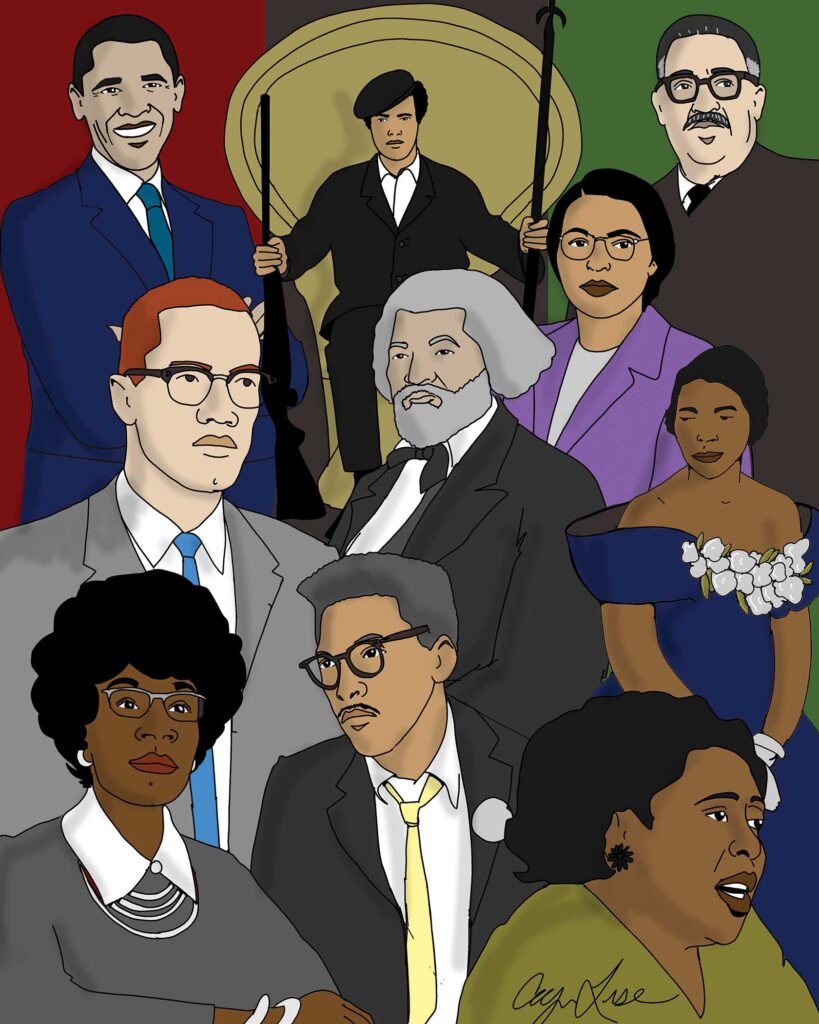

As February starts, we begin another Black History Month in America. The winter celebration of our history and heritage traces its origins to Harvard scholar Dr. Carter G. Woodson, creator in 1915 of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. In 1926, as the Harlem Renaissance blossomed and Marcus Garvey drew huge audiences on a message of Black pride and empowerment, Woodson launched Black History Week. Highlighting the accomplishments of such figures as the formerly enslaved orator and writer Frederick Douglass served as a counternarrative to the growing influence of the Ku Klux Klan and the false prophets of racism and eugenics.

Woodson deeply and rightly believed in the value of celebrating the wonderful contributions of African Americans to this country from its beginnings in the first settlements along the Atlantic coast. The story of slavery and Jim Crow dominates the first three centuries of African presence on the North American continent. Profiteers in human bondage suppressed stories of Black talent in order to degrade the value of African American life and our contributions. But this sub-human representation of African people long predated the establishment of slavery on our shores. European slave-traders deemed it necessary to dehumanize the slave in order to justify their oppression. The European gentry wanted to present themselves in a good light, not as evil people, so they turned African slaves into something less than human to rationalize enslaving them. There were even those who argued that enslavement provided Africans the opportunity to learn new skills, a sentiment shockingly echoed more recently by a certain American politician. The racist propagandists simply overlooked the fact that Africans were masters of science, agriculture, engineering and architecture for thousands of years before Europeans, borrowing from African technology, established their own cities.

Since the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s, there have been many attempts to tell the myriad stories of the true history that makes up the African American experience. The most prominent example of the monuments to our people is the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. The popular attraction presents our shared history of African American struggle from pre-enslavement and Jim Crow through the civil rights movement to the election of President Barack Obama and the present. The museum embraces the music, arts, culture, inventions, politics, military service, travel, pain and joy of the entire African American experience.

And we in Boston are justly proud of our own Museum of African American History and the iconic African Meeting House on Beacon Hill, where so many important figures of the abolitionist, civil rights and racial justice movements have spoken truth to power from a pulpit built by Black hands.

Though our national African American history celebration spans only one month, it is important that we teach and learn African American history every day — all over America. That history has been largely left out of textbooks. And it still faces active threats of removal. School systems around the country are canceling Black history out of a misguided sense of racial grievance, as if trumpeting Black history somehow cancels or diminishes others. Make no mistake. This is a movement that wants to turn back the clock of time and deny or hide racial wrongdoings. Clearly, some hope that suppressing past injustices will somehow absolve our country from taking account and accepting responsibility to make up for centuries of exploitation.

We cannot move forward in a society with systemic racism and oppression, with a rigged legal and economic system. We cannot allow those imbalances to continue. We as a nation must compensate victims for the centuries of oppression our ancestors endured and that we continue to suffer. We throw away so many brilliant Black children by minimizing their opportunity for a good education by pre-judging them or consigning them to second-class schools — and then blaming them for falling behind as too many end up behind bars.

African American history must be shared each and every day as part of the process of addressing the past and moving into the future. A better national understanding of how our economic and educational systems were rigged against Black Americans provides a more solid basis for understanding the joy, pain and humanity of our people. That in turn will help create the impetus to account for the damage done, accelerate the process of providing reparations for that harm, and finally create the equal society our country deserves.