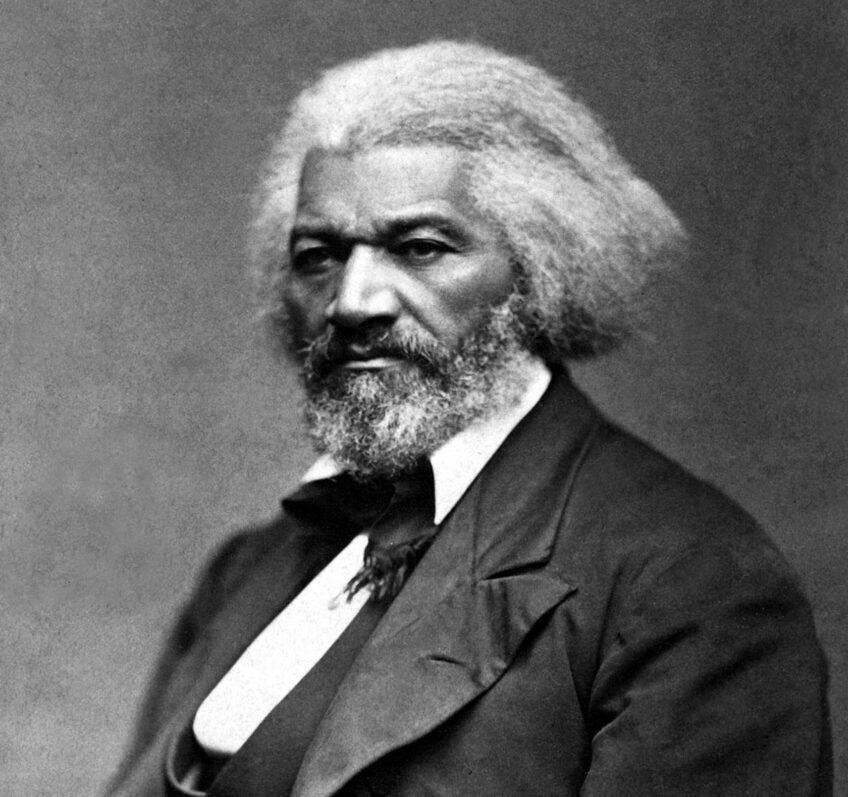

This is the image of the quintessential single-issue climate voter we’re likely to see in the mainstream media: someone who is white, possibly a woman, probably highly educated and she drives a Prius, if not some other kind of fully electric car. It’s an image that’s existed for as long as there has been such a thing as a climate-change voter. But it’s nothing more than that: an image, not a reality.

“It’s a narrative that’s been created that white people are interested in climate and are tree-huggers, and Black people are not,” says Andre Perry, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institute. “Meanwhile, Black people are much more likely to deal with the day-to-day impacts of climate change.”

New research published by Brookings last month (Perry was a coauthor) shows that not only do Black Americans care about climate change, they care more than the average voter — and depending on where they live, sometimes far more. It’s research that shows climate policies should not solely be targeted to this bygone notion of a green voter, but can and should specifically address the needs of Black Americans, who face very specific climate risks.

According to the research, some 88% of Black voters “are concerned about climate change to some degree,” Perry and his coauthors Manann Donoghoe and Justin Lall write — which is 9.6 points more than the national average of 78.4%, and fully 12 points above white voters.

Looking state by state, the gap between Black voters and all voters is sometimes dramatically larger — but perhaps counterintuitively, this tends to be the case in states that have smaller Black communities. So in Oregon, to give the most dramatic example, Black people are 25.2 points “more likely to be concerned about climate change” than the average voter in the state, while in Louisiana — in many ways the poster child for the specifically Black risks of climate change — Black voters are actually slightly less likely (by 3.64 points) than the state average to be concerned about climate change.

Perry chalks this up to two things. One, that Black voters, while following certain population-wide trends, are still not a monolith; and two, the success of efforts by politicians and others in places like Louisiana to minimize, if not outright deny, the effects of climate change.

“I’m never surprised to see that where there have been campaigns to dispute climate change, that Black people have bought into those false narratives too,” he says. “Those deniers don’t just suppress policy, they suppress knowledge and truth overall.”

But knowing the importance of climate issues to Black voters presents politicians with the opportunity to better tailor climate policy to them — and they could even overcome some of that denial in the process.

“The more we can put climate change in the context of lived experience, the better,” Perry says. That could mean addressing the growing swath of the South, including many predominantly Black communities, where more homes are becoming more expensive to insure, if not outright uninsurable. Or the related issue of repeat flooding in certain low-lying areas where Black families have been pushed into living since the days of redlining.

“I think there’s a real opportunity to talk about climate change in a way that makes sense to how people are living,” Perry says, “and that’s how we’re going to make change overall.”

Willy Blackmore is a freelance writer and editor covering food, culture, and the environment. This article appeared in Word in Black.