“Auld lang syne” will be sung this year for notables from the worlds of sports, politics, activism and entertainment. The Bay State Banner has chosen a dozen figures, six of local renown, to represent the passage of meaningful lives in 2023.

Mukiya Baker-Gomez (1948-2023)

A montage of campaign victory celebrations in Black Boston over the last 40 years would all capture ebullient candidates addressing happy supporters, but the images would also likely include the figure of Mukiya Baker-Gomez at the edge of the stage or in the background.

Baker-Gomez, an indefatigable campaign and community operative, had a hand in sending numerous candidates to careers in Boston City Hall, the Massachusetts State House and even Capitol Hill over the course of a half-century of political work.

She knew the players and knew the neighborhoods, but also knew the voters, as a result of knocking on thousands of doors. She had an outsider’s instinct for what it took to stir things up and an insider’s knowledge of how things worked from holding staff positions in politics and government.

Her political acumen vaulted Gloria Fox to the State House and Chuck Turner and Ayanna Pressley to the Boston City Council. She was a tireless worker in Mel King’s mayoral campaign. Her management of Dianne Wilkerson’s upset win over incumbent state Sen. Bill Owens in the Second Suffolk District race was her most public victory in a career of many quiet accomplishments.

Harry Belafonte (1927-2023)

Who could ever imagine that a tall, impossibly handsome West Indian singer would become a leading light of civil rights in America? But that’s who Harry Belafonte became, trading on his lilting tenor and electric screen presence to advance the cause of freedom around the world.

“I wasn’t an artist who’d become an activist,” wrote Belafonte in his 2011 memoir. “I was an activist who’d become an artist. Ever since my mother had drummed it into me, I’d felt the need to fight injustice whenever I saw it, in whatever way I could.”

Known as the “King of Calypso” in the 1950s, Belafonte headed up protest marches in the early 1960s with the Rev. Martin Luther King, helped finance Freedom Summer in Mississippi and put his life at risk to deliver the funds.

He later put his celebrity to work in the cause of battling apartheid in South Africa. He helped engineer Nelson Mandela’s triumphant U.S. tour after his release from prison, and to his very last days battled the forces of oppression.

Jim Brown (1936-2023)

Other football players broke his records, won more games and lifted more trophies — but no one, simply no one, in the history of the NFL competed with the same force and impact as Jim Brown.

From the moment he entered the NFL out of Syracuse in 1957, he set a new standard of speed, power and agility, running around or right over hapless defenders, who often compared collisions with Brown to an encounter with a freight train.

Brown played nine seasons with the Cleveland Browns and left at the top of his game, having won the rushing title eight times and being named three-time league MVP. He gave up football for acting and activism, sharing the screen with Raquel Welch and organizing support for Muhammad Ali’s refusal to fight in Vietnam.

His blunt-spoken persona rubbed some people the wrong way, and a string of abuse and assault charges, including domestic violence, tarnished his tough-guy luster.

William H. Dilday Jr. (1937-2023)

The Dilday brothers were high achievers. Two of them, James and Clarence, made their marks in courts of law. William, the eldest, became a pioneer in the broadcast industry, breaking down barriers in front of and behind the cameras.

After attending English High and Boston University and serving in the Army, Dilday was hired in 1962 as personnel director for WHDH-TV in Boston. Just a few years later, after urban riots sparked by police brutality left cities aflame, the federal Kerner Commission made far-reaching recommendations to quell the fires next time, including a sea-change in the depiction of African Americans in the media.

When a Jackson, Mississippi, TV station lost its broadcast license in a landmark 1969 Supreme Court decision because of racist comments on air, Dilday got the call to become the nation’s first Black general manager of a network affiliate. He integrated WLBT’s anchor desk and children’s shows and promoted positive stories of Black life.

A founding member of the National Association of Black Journalists, Dilday joined a Black ownership team that purchased a St. Croix station in 1973 in the U.S. Virgin Islands and became the general manager and executive vice president of the CBS affiliate WJTV in Jackson.

Saundra Graham (1941-2023)

In the long annals of institutional expansion in Boston, Saundra Graham will forever be remembered as the Cambridge mother who stopped Harvard cold, mounting a protest at the university’s 1970 commencement and getting the school’s hands off the heavily Black Riverside neighborhood.

Already an activist by then in “the Coast,” one of America’s oldest Black communities, Graham served on local boards and led opposition to Harvard’s efforts to raze family housing to make way for dormitories. Her successful protest launched a long career in politics. She served as Cambridge’s first Black woman city councilor as well as a state representative on Beacon Hill.

Her work in housing at both the city and state levels was critical in preserving and expanding affordable housing stock. She was also a champion of child care and served as founder of the Massachusetts Childcare Coalition.

Cambridge honored her long contributions to public service by the renaming of the Graham & Parks School, preserving her memory with that of fellow civil rights icon Rosa Parks.

Willard R. Johnson (1935-2023)

Professors and teachers, if they’re lucky, manage to leave their imprint on a handful of students every year of their career. But Willard R. Johnson left his mark on the world.

While serving as the first Black tenured faculty at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Johnson in 1977 co-founded

TransAfrica, a small and underfunded lobbying group focused on Africa and the Caribbean. By the early 1980s, TransAfrica had grown in size and influence to become the leader of U.S. opposition to South African apartheid.

As head of the Boston chapter, Johnson applied relentless pressure on the South African government, organizing national protests at the white regime’s D.C. embassy and staging pickets at the Boston office of Deak-Perera, where gold Krugerrand coins from South Africa were sold. His advocacy helped spur the passage of a South African divestment bill in the Massachusetts legislature over a governor’s veto, while sanctions legislation on Capitol Hill became law after overriding President Reagan’s veto.

Tall, angular and soft-spoken, Johnson embraced African liberation studies early in his career, earning degrees from UCLA, Johns Hopkins and Harvard before joining the MIT faculty in 1964. He recognized the power of global and grassroots alliances and saw in Africa a strong partner in lifting Black Americans out of segregation and economic despair.

Mel King (1928-2023)

The courtly, dependent era of Black politics in Boston ended with the ascension of Melvin H. King, who forged coalitions to make insistent demands for power and inclusion in the city’s tribal political culture.

Equal parts academic and activist, politician and polemicist, King cultivated a wide following from his base in the South End, which he represented at the State House and where generations of political acolytes came to the King home for his famous Sunday brunches.

His 1983 run for mayor ended up with King losing his bid as the first Black finalist in Boston history but established the model of the Rainbow Coalition for others to follow, including the Rev. Jesse L. Jackson’s campaigns for president. Progressives flocked to King’s mayoral message of empowerment, sending Black voter enrollment and turnout skyrocketing.

The Boston native, raised in the “New York Streets” neighborhood, now home to glass-and-steel lofts, began his career as a settlement house worker. He stood up against the segregationist Boston School Committee and fought urban displacement. He famously dumped table scraps on the white linens of a United Fund philanthropy luncheon to protest the dispensation of “crumbs” to Boston’s Black community.

But King also wrote poetry and preached love, mentored generations of students as an MIT professor and left a long legacy of activism and progressive change, especially in affordable housing, that endures today.

Norman Lear (1922-2023)

A Jewish kid from Chelsea, Massachusetts, Norman Lear briefly attended Emerson College in Boston before enlisting in the Army Air Corps during World War II. On bombing missions over the Mediterranean, the all-Black “Red Tails” squadron of the Tuskegee Airmen protected the young gunner and the crew from enemy aircraft.

Lear called his Tuskegee protectors “the Nicholas Brothers in the air,” comparing their aerial theatrics to the dazzling leaps of the famed dancing duo. In other words, a rock-solid foundation for seeing beyond stereotypes and prejudice to the essential character and potential of African Americans.

In his 80-year career as a producer, Lear reshaped the images of Blacks in American media, bringing real characters facing real issues to the small screen. African Americans appeared as middle-class strivers, business owners, and solid two-parent family units in shows like “Sanford and Son,” “The Jeffersons” and “Good Times.”

His breakthrough show, “All in the Family,” tackled social and racial issues with humor and irony, using Archie Bunker as a political weather vane to portray the changes of a turbulent era. And who could forget Sammy Davis Jr., planting a kiss on the shocked face of the Everyman from Queens?

Charles J. Ogletree Jr. (1952-2023)

His sonorous baritone and deceptively simple phrasing made the Harvard Law professor a star of the classroom and the courtroom, drawing in juries and students alike with his charismatic and persistent questioning.

Charles Ogletree, known as “Tree” to friends, came to national prominence with his able and artful representation of Anita Hill during her Capitol Hill crucifixion by backers of Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas.

Born into a family of California farmworkers, Ogletree transformed the lived experience of poverty and abiding faith into a career devoted to defending the destitute and shaping the law into a force for more equitable justice. He taught future presidents like Barack Obama and mentored Boston kids caught up in gang life.

Jesus made disciples out of fishermen. You can almost imagine the Lord whispering in Ogletree’s ear as he cast for stripers off his beloved Martha’s Vineyard.

Randall Robinson (1941-2023)

A childhood in the segregated South taught Randall Robinson all he needed to know about injustice. He spent the rest of his life working to correct it.

The Virginia native and Harvard Law grad went to Washington to work on Capitol Hill after a stint in community development at the Roxbury Multi-Service Center. He co-founded TransAfrica with Willard Johnson, and as head of the Free South Africa Movement coalition was the towering public face of anti-apartheid protests, sit-ins and forums.

He lobbied for the restoration of democracy in Haiti and the return of ousted President Jean-Bertrand Aristide to power. His unsuccessful efforts to engineer reparations for the descendants of slaves in America led to self-imposed exile, and he spent the last 20 years of his life in St. Kitts, teaching and writing and woodworking.

Robinson wrote “Quitting America: The Departure of a Black Man from His Native Land” but never ended his advocacy for broader acceptance of Black civil rights and economic empowerment from a nation whose power and wealth was built on the backs of slave labor.

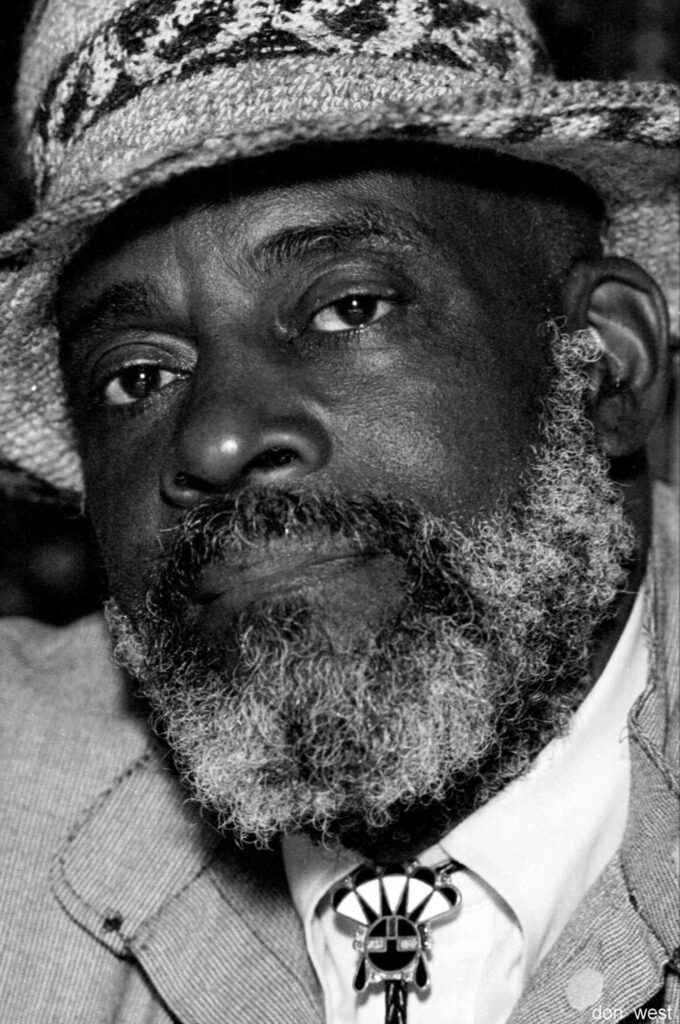

Richard Roundtree (1942-2023)

The era of genteel integration of Black faces in Hollywood — personified by Sidney Poitier’s upright and morally righteous screen presence — ended in 1971 with the arrival of “Shaft” and Richard Roundtree.

The lithe actor swaggered like a panther on the big screen, talking big and living large, his brown leather coat flowing behind him along the gritty, wind-swept streets of New York. Roundtree’s depiction of a confident and unapologetically Black private detective pulsed to the beat of Isaac Hayes’ brilliant score, with audiences screaming out the end of the elided line, “He’s a bad mutha…”

The former model and stage actor ushered in the “Blaxploitation” era of film-making, but he also drew attention to the issue of male breast cancer after his own diagnosis in 1993, sharing his story and using his own vulnerability to add texture to the legendary profile of a strong Black man.

Tina Turner (1939-2023)

When the former Anna Mae Bullock from Nutbush, Tennessee, walked out on her abusive husband and musical partner, she had 36 cents in her pocket. But her light would not be hidden by a bushel basket. She lived with friends and survived on food stamps and within 10 years, Tina Turner sat astride the entertainment world, starring in feature films, performing in sold-out arenas, and joining with some of the biggest rock acts on the planet to create epic duets.

She was barely out of her teens when she met Ike Turner in East St. Louis and was soon singing back-up in his rhythm & blues band. The hits started coming, but so did abuse. Tina recorded “River Deep, Mountain High” with Phil Spector in 1966, with Ike, fuming, excluded from the studio. Their hit “Proud Mary” in 1971 signaled a shift to rock-oriented material and crossover success.

Turner’s dramatic escape from her husband in 1976 did not go unnoticed by rock cynosures like David Bowie and Mick Jagger, who had been stunned by her powerful vocals and provocative stage presence. Collaborations ensued, along with movie roles like Aunty Entity in “Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome.”

As Turner reached her 50s, her life began revolving more closely around her Baptist and Buddhist faiths and life in Zurich with German record producer Erwin Bach. “What’s Love Got to Do With It?” she asked, in the title track to her film biography starring Angela Bassett as Tina. Everything.