A chronicle of Black life in Boston

The art of Allan Rohan Crite at Boston Athenaeum

“I was an artist-reporter, recording what I saw,” said Allan Rohan Crite (1910-2007), whose captivating paintings depict daily life in the Black community of Boston’s South End and Roxbury neighborhoods during the 1930s and ’40s.

Crite painted what he knew. A graduate of both the School of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and Harvard University, Crite lived at 410 Columbus Ave. in Boston’s South End, a few steps from the newly dedicated Crite Park. A plaque on his row house recognizes Crite as a “Master Visual Artist, Painter, Printmaker, Author, Lecturer, Historian and Good Neighbor.”

Now, 11 of Crite’s paintings are on view at the Boston Athenaeum, a member-supported library, museum and cultural center in sight of gold dome of the State House on Beacon Hill.

Crite was a member, and donated many works to the Athenaeum, founded in 1807 and located since 1849 at its current Beacon Street site, a National Historic Landmark building. With newly renovated quarters that almost double its size, the Athenaeum has expanded its exhibitions that encompass the multicultural and multiethnic heritage of America and in particular, Boston. The Athenaeum welcomes visitors, who for a small fee can see its public exhibitions and, by appointment, research its special collections.

The Athenaeum is organizing a major Crite exhibition for fall 2025, and in March 2024 will present “Framing Freedom: The Harriet Hayden Albums,” which explores the visual culture of Boston’s Black abolitionist community in the 1860s.

The Crite works now on view begin in the Henry Long Room, where the exhibition “Re-Reading Special Collections” juxtaposes three of his paintings with rare books, works on paper, paintings and sculptures spanning three centuries.

With modernist economy and a zest for the music of human movement and the patterns visible in daily life — from swirling striped skirts to the shapes of South End row houses, Crite recorded what he saw in a warm amber palette often accented by signature dabs of yellow.

In “The News” (1945), four men on the corner of Columbus Avenue and Northampton Street read newspapers reporting the death of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on April 12, 1945. The white folds of the newspapers center the urgent and absorbed figures of the men, who with expressive faces and elongated bodies include a soldier and men in business attire.

In “Late Afternoon” (1934), families wearing their Sunday best mingle along a tree-lined street. Equal in prominence to the figures in the foreground is a black cat and a boy with bandy legs observed by his smartly dressed father.

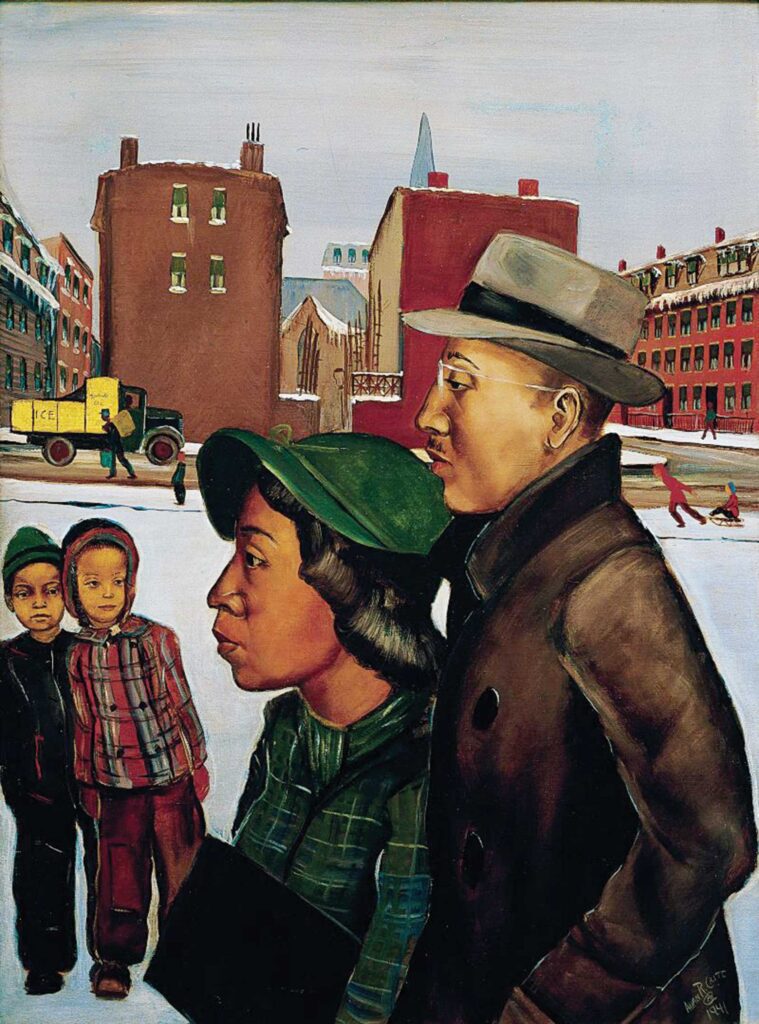

“Harriet and Leon” (1941) renders an elegant man and woman in profile. Observing this couple as they stride with purpose are two curious boys. Behind them, under a mottled winter sky, a man unloads boxes of ice from his truck and a boy pulls a child on a sled.

Also in the Long Room are early editions of works by poet Phillis Wheatley (1753-1784), enslaved by the Wheatley family of Boston, including her “Poems on Various Subjects,” the first book published in North America by a person of African descent. Nearby are two fine paintings by Robert S. Duncanson (1821-1872), a leading American landscape painter during the Civil War era. Born to free Black parents, he often journeyed at great risk to paint scenes below the Mason-Dixon Line.

Eight more of Crite’s paintings await visitors in adjoining rooms, each overlooking the Granary Burying Ground, a landmark on the Freedom Trail.