Say their names: ‘Call and Response’ explores horrific history of medical testing on enslaved people

A new exhibit at Harvard University explores the horrendous histories of nonconsensual medical testing on enslaved women and girls. In 24 artworks, the female victims of these atrocities are named, honored and avenged.

The exhibit at the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research, mounted in partnership with the Resilient Sisterhood Project, spotlights the history of Dr. James Marion Sims, who performed experimental surgeries on enslaved Black females in Alabama during the mid-19th century.

Sims is dubbed the “father of gynecology” because of his research into vesicovaginal fistulas, a severe complication often caused by prolonged labor. These abdominal injuries frequently occurred in enslaved females due to malnutrition, repeated rapes and numerous pregnancies.

“Mothers of Gynecology” by Michelle Browder. Mixed-media miniature sculpture, 2023. PHOTO: COURTESY OF MELISSA BLACKALL AND THE HUTCHINS CENTER FOR AFRICAN AND AFRICAN AMERICAN RESEARCH, HARVARD UNIVERSITY.

The identities of all 12 females that Sims subjected to experiments are not known, but there is historical evidence of three: Lucy, Betsey and Anarcha. To refer to them as women would be misleading, as the group ranged in age from 13 to 23.

Sims operated on 17-year-old Anarcha more than 30 times. To make matters more sinister, he refused to use anesthesia although it was available at the time. He claimed that Black women were impervious to pain.

“He’s a hack and a showman, mostly,” says Dell Hamilton, curator of the “Call and Response: A Narrative of Reverence to Our Foremothers in Gynecology” exhibit. “He’s the P.T. Barnum of medicine. And he’s not an exception — he was the rule.”

Hamilton explains that during that historical period, medicine was not a codified scientific field with oversight, processes and dictated moral standards, which made the field ripe for medical racism and unverified information. Though there may not have been enforced standards of practice, many of Sims’ medical colleagues refused to participate in his experiments because of the horrific pain the women and girls experienced.

In addition to suffering experimental procedures, they served as Sims’ surgical assistants. In her book “Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology,” historian Deirdre Cooper Owens writes, “They learned the fundamentals of gynecological surgery from arguably the most successful gynecologist of the nineteenth century. During the five years they lived on Sims’s farm they helped him birth a new field.” Of course, those contributions have been uncredited, just as the torture they suffered has been.

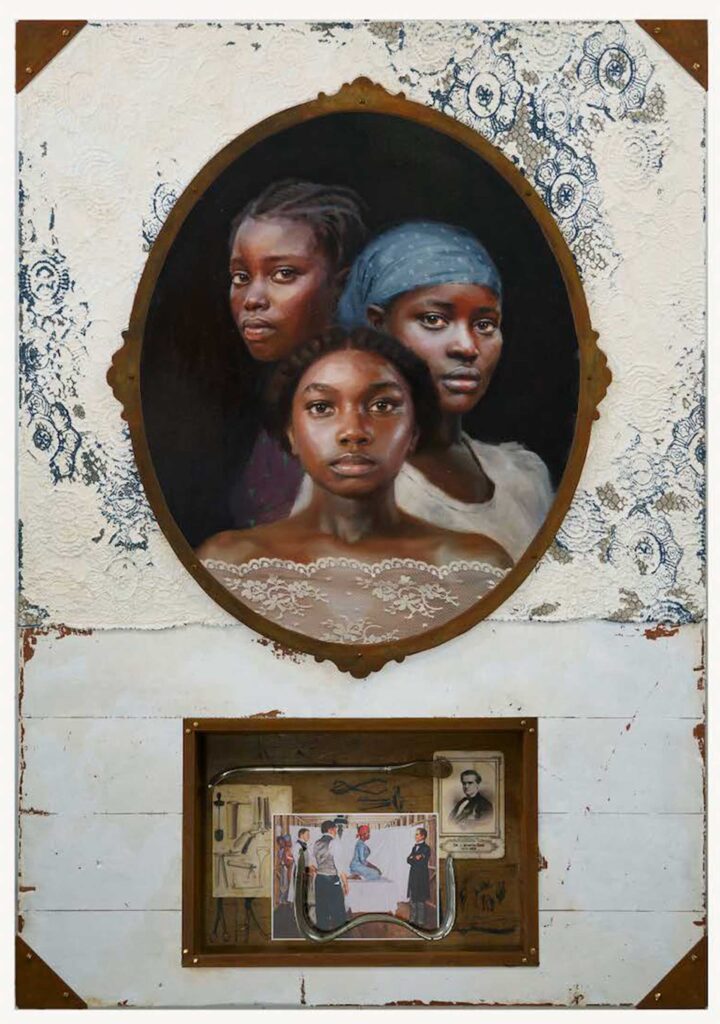

Lucy, Betsey and Anarcha are the central figures of the Harvard exhibition. The base of the show is a series of paintings by Jules Arthur. The Resilient Sisterhood Project commissioned three of the paintings in 2019, and three more were produced for this exhibition. In Arthur’s paintings, Lucy, Betsey and Anarcha are depicted as angelic.

In one, an oval portrait shows the three as they might have been, with unique features and selfhood, not merely names on a page. Below them are a framed box holding some of the instruments used by Sims, alarmingly similar to gynecological tools still used today, and a widely distributed racist illustration by Robert Thom from the 1950s of Sims examining Lucy. This juxtaposition centers Betsey, Lucy and Anarcha in the narrative and probes what they endured.

“There’s a beautifully rendered, thoughtful, dignified presentation of this history,” says Hamilton. “And then again, also grappling with the complexity of the lives of enslaved Black women who have little to no agency in the way they conduct their lives.”

“Field of Exploitation” by Jules Arthur. Mixed-media painting, 2023. PHOTO: COURTESY OF MELISSA BLACKALL, THE RESILIENT SISTERHOOD PROJECT AND THE HUTCHINS CENTER FOR AFRICAN AND AFRICAN AMERICAN RESEARCH, HARVARD UNIVERSITY.

In a series of works by Michelle Hartney, the three are memorialized in mixed-media sculptures with their names embroidered on what look like honorary military ribbons. The use of embroidery alludes to female-dominated art forms, which some critics demote to “women’s work” versus high art, and the use of military motifs honors their suffering.

Next to each mixed-media piece is a framed vintage obstetrics textbook praising Sims and his research. Hartney has added text to each one, amending it to explain Sims’ exploitation of enslaved women and girls. These textbooks are often still accessible in libraries, and Hartney has a running list of institutions in the U.S. circulating them. She encourages viewers to find the texts and add their own amendments.

Arthur’s saintly portrayals represent one end of the show’s spectrum, centering the women and their experiences. On the other end is a video piece by King Cobra (documented as Doreen Lynette Garner), showing Black women dissecting a corpse made of silicone, glass beads, urethane foam and other materials. The corpse is modeled after a statue of Sims that was removed from New York City’s Central Park in 2018 after extensive activist protests. Here, revenge is extracted as the women pull bloody bits out of the corpse, returning the pain wrought on Lucy, Betsey and Anarcha by performing the same operation on Sims.

Though “Call and Response” specifically focuses on Sims, his story is one of many in history. Medical abuses of the Black body were prevalent, even in more recent history. A few notable cases include the harvesting of cells from tobacco farmer Henrietta Lacks without her knowledge or consent to use for cancer research in the 1950s; sisters Minnie Lee Relf, 12, and Mary Alice Relf, 14, who were involuntarily sterilized at a clinic in the 1970s; and the U.S. Public Health Service’s Syphilis Study at Tuskegee between 1932 and 1972 that observed the progression of untreated syphilis on 600 Black men (399 with the disease, 201 without) without their consent and without offering treatment.

This legacy lives on in contemporary health care. According to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Black women are still three times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause than white women. Factors such as variation in health care quality, structural racism, implicit bias and underlying chronic conditions contribute to that disparity.

The overturning of Roe v. Wade in 2022 and the ongoing legislation against gender-affirming care (22 states have enacted laws restricting it) continue to illustrate strains of racism and gender bias in contemporary healthcare.

“Anarcha” by Michelle Hartney. Mixed-media diptych PHOTO: Courtesy of the artist and the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, Harvard University

Hamilton, the curator, says she and many of the Black women in her life have felt they are not heard or believed by medical professionals, even in a standard primary-care setting.

These disparities are exactly what the Resilient Sisterhood Project is working on. The nonprofit focuses specifically on diseases of the reproductive system such as PCOS, or polycystic ovary syndrome, cervical cancer, HPV, endometriosis and many others. Educational workshops are at the core of the program’s work, spreading understanding and awareness about the conditions themselves as well as the inequities Black women experience in care.

“It is important to ensure that Black women’s reproductive health rights and justice are addressed, whether it’s focusing on diseases or on getting appropriate services that we might need,” says Resilient Sisterhood Project Founder and Executive Director Lilly Marcelin. “But we know that there is a history of health inequities, a history of medical malfeasance of Black bodies.”

“Call and Response: A Narrative of Reverence to Our Foremothers in Gynecology” has been extended through the end of the year. The exhibit is open to the public in the Hutchins Center in Harvard Square Monday through Friday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Visitors can request guided tours in advance by e-mailing Hamilton from the exhibition web page.

“I do hope that [viewers] see themselves as ambassadors who really need to go out there and talk to everyone, but especially to our young people, and to encourage them to learn those stories, to remember the stories, to share the stories one generation after another,” says Marcelin. “Because I believe this is the way for us to continue to provide justice and love and grace and compassion to our ancestors.”